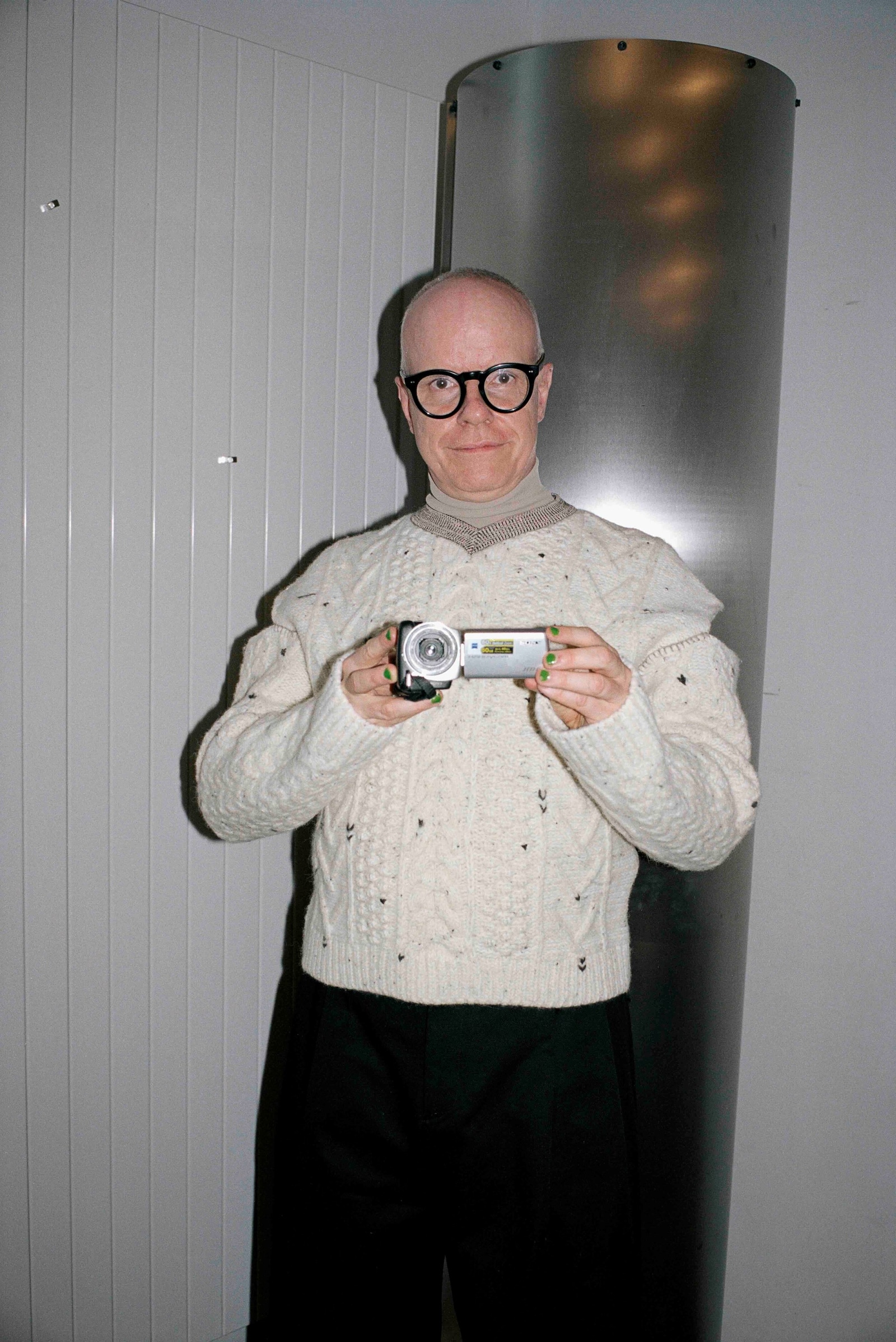

Hans Ulrich Obrist is famously prolific. As both artistic director of the Serpentine Gallery and an independent writer and curator, he produces an overwhelmingly busy schedule of talks and exhibitions, alongside long-running projects, some of which have been in the works for over three decades. Alongside this, he has now published his coming-of-age memoir Life in Progress, exploring how his early life and a near-death experience in childhood fuelled an insatiable appetite for meeting artists and staging shows, from his own kitchen to world-class institutions.

“My other books are very matter of fact,” he tells me, when we speak ahead of the launch. The book was first published in France, with Obrist writing it during lockdown. “The others are about a specific artist or the history of curating … [My French publisher Seuil] felt it might be of interest to do a personal book but there was never the time. At least at the beginning of lockdown, before all the Zoom calls started, there was a bit of time! The death of my mother was also an important aspect.”

When he was six years old, Obrist was knocked down in the street by a speeding car. “It created a sense of urgency that has never left me. I have an urgency to get things done.” He describes this moment between life and death as an “awakening”, realising that “life is a gift, and we need to make the most of it”. While bedbound in hospital, he immersed himself in books. “A whole chain reaction unfolded. Through books I got more into literature, then more into art. I began to collect postcards and artworks, started an imaginary museum in my childhood bedroom.” He has since “lived surrounded by piles of books from the floor to the ceiling.”

Obrist’s family were not particularly interested in art. While in her later years, his mother made art, he notes that her way in was through him sending her catalogues as an adult. In childhood, home “wasn’t really a cultural environment”. He discovered art through those who might be considered outsider, or big names who engaged with more accessible means of sharing their work. Obrist mentions Harald Naegeli, the Swiss graffiti artist whose characterful swirling figures, a protest against urbanisation, filled the public walls of Zurich in the 1970s and 80s. He discovered the iconic US artist and activist Keith Haring through public film festival posters, and kinetic sculptor Jean Tinguely thanks to his Swiss chocolate packaging designs that lined the walls of Obrist’s childhood bedroom.

As such, an aspect of accessibility and unconventional placement has run through much of his curatorial work. “Art came to me through all these different channels,” he says. “Retrospectively, if I look at my curatorial activities, I have often done shows in unusual museums, or on aeroplanes and trains.” The first exhibition he ever staged was in his kitchen in St Gallen, Switzerland, in 1991. The Kitchen Show featured emerging artists who are now household names, such as Peter Fischli and David Weiss, Christian Boltanski and Richard Wentworth.

Before curating his first exhibition, Obrist spent his late teens travelling Europe by train with an Interrail ticket, visiting 30 different cities in as many days. “I couldn’t afford hotels,” he says. “It was a great adventure.” He would call up artists in each city, speaking with his contemporaries, many of whom he foresaw as the historic figures of his time, inspired by Giorgio Vasari’s 16th-century book Lives of the Artists. His first studio visit was with Claude Sandoz in Lucerne; he had recently designed the artwork for the annual railway timetable. “I was so fascinated by that, I looked at it every single day.”

This was followed by a visit with Fischli/Weiss, which began a decades-long creative conversation. He began to meet curators and museum directors, with artist Jonas Mekas convincing him to start recording every conversation in the 90s. “Art is a gateway to possibilities, and I think that’s still the case,” he considers. “To summarise my whole experience, I just went out and found mentors all over the world, and I think there is still an openness for that. Obviously now it would be more of a mixed reality thing. But I do think even in this digital age, nothing can replace one-to-one, in-person encounters.”

“It’s very important that we bring different fields together and go with the idea of sharing knowledge” – Hans Ulrich Obrist

Many of his relationships have become sprawling and ongoing, and he names the philosopher Roman Krznaric as an inspiration. Krznaric rejects contemporary short-termism, which is driven by deadlines and a quick turnaround project mentality. “I am very interested in doing exhibitions that can evolve over many years,” says Obrist. “Almost like an algorithm that can learn, feed back and grow – these exhibitions are smarter after two or three years. My exhibitions don’t have a fixed, rigid masterplan at the beginning.”

The book also explores his ongoing interest in combining disciplines, an aspect that comes to life in his union of art and architecture every year in the Serpentine Pavilion. He tells me that when he joined the gallery in 2006, Julia Peyton-Jones’ launch of this project was a big draw. He also wants to break down the boundaries between art and science, as seen in the Serpentine’s Laboratorium research platform and multi-disciplinary ‘marathons’. “We can only address the big topics of the 21st century if we go beyond these boxes and separations,” he says. “It’s very important that we bring different fields together and go with the idea of sharing knowledge.”

Ultimately, he hopes for the book to encourage a DIY mindset within the creative worlds. “I didn’t have any access, it’s not like my parents opened doors in the art world,” he tells me. “I always had this DIY approach. I think my methodology could be applied in lots of different fields.” He sees his role as a “junction maker” bringing together objects, people and ideas. “In the traditional sense, the curator is the caretaker of artworks,” he says, considering how his early accident imbued him with a keen interest in the role of care and longevity. “Art is a way to go beyond death.”

Life in Progress by Hans Ulrich Obrist is published by Allen Lane and is out now.