This immersive film opens a portal into the trippy imagination of Carlo Rambaldi, the artist who created monsters for David Lynch, Steven Spielberg, and Ridley Scott

Audiences with a ticket for Alien Perspective at the Venice Film Festival this year were projected onto imaginary planets with mushrooming forests, subterranean caverns and gigantic, glowing moons. The VR project draws its visuals from the futuristic, fever-dream paintings of the late Carlo Rambaldi, a special-effects virtuoso who created mind-bending monsters for the likes of David Lynch, Steven Spielberg and Ridley Scott. To mark the centennial of Rambaldi’s birth this autumn, his granddaughter, LA-based actor and producer Cristina Rambaldi, and filmmaker Jung Ah Suh, are seeking to unleash Rambaldi’s hyperactive imagination on a new generation: “We used VR not just to be able to enter his paintings but make the experience of looking at Rambaldi’s works intimate – make it inclusive, emotional, and to connect,” says Jung.

Together they’re reinvigorating Rambaldi’s legacy using technology he himself never had the chance to experiment with – the ingenious artist and three-time Oscar winner created his own works out of more tangible stuff: hydraulic pistons, steel, latex and levers, toiling in the workshops of Rome’s famed Cinecittà Studios. Through the 60s and 70s, he worked on grisly giallos for the likes of Dario Argento, made winged mannequins for Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Arabian Nights, and provided the carnage in Andy Warhol’s exuberantly camp horror-satires Frankenstein and Dracula. His skill for realistic bloodshed almost landed one director in jail: 1971 Italian horror A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin featured an orgy on the London underground, a vicious colony of bats roosting in Alexandra Palace, and a gruesome scene in which six dogs are vivisected in a lab. Its director, godfather of gore Lucio Fulci, was threatened with two years’ imprisonment for animal cruelty – until Rambaldi wheeled the dogs into an Italian courthouse to prove they were in fact highly realistic mechanical puppets.

In the mid-70s, Rambaldi’s gift for conjuring otherworldly monsters caught the attention of Hollywood and he left for Los Angeles to construct a 42-ft mechanical ape – King Kong – that was a marvel of hydraulics, valves and pistons, with 1,012 lbs of horsetail sewn onto its latex skin and a hairy palm so enormous Kong’s co-star Jessica Lange could sit inside it.

During the 70s and 80s, Rambaldi was responsible for the expressive humanoid aliens of Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the colossal sand worms with their ice-pick teeth in David Lynch’s Dune, and the goo-dripping parasitic monster with retractable jaws in Ridley Scott’s Alien, based on HR Giger’s design. But his most famous is a more cuddly and lovable creation: Spielberg’s wrinkly, stranded alien E.T., imagined by Rambaldi as a combination of his pet Himalayan cat, Donald Duck’s waddle and Albert Einstein’s forehead.

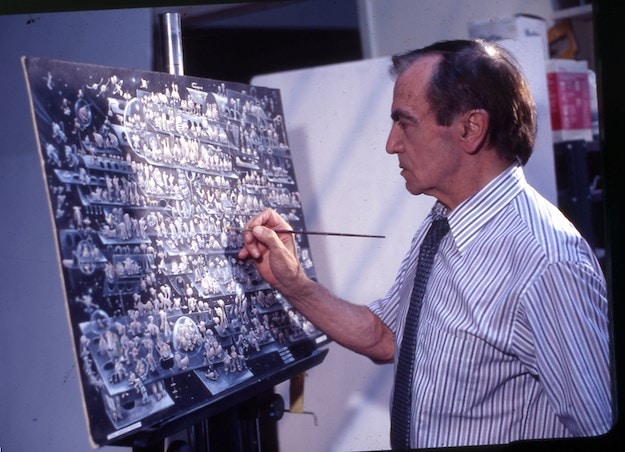

“He had many studios, what he called ‘laboratories’ – in Northridge in LA and in Rome, where monsters were made, where he continually painted and experimented with little mechanisms,” remembers his granddaughter. “He was prized for his ability in mechatronics, but I think he was so successful because he was able to find the poetry in that intersection between art and technology – I think to imagine a creature like E.T. required poetry as well as skill.”

As the 90s dawned though, Rambaldi found demand for his alchemical tinkering waning: “With the effects of Jurassic Park and CGI, he started going back to painting, which is where he started as a student, at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna,” says Cristina. (It was while studying there that he developed his fascination for skeletal and muscular structure that served him so well in his future career.)

When Rambaldi died in 2012, he left behind a trove of sketches and sculptures – and paintings that captured the hallucinatory futurescapes viewers are now able to wander through in Alien Perspective, encountering uncanny extra-terrestrial life forms along the way. It’s a harnessing of new technology that ensures the poetry and personality Rambaldi brought to his otherworldly visions lives on in unexpected ways – an approach they believe he would have approved of.

“My grandfather was at a certain point a little wary of the digital,” says Cristina. “So we were very careful. But we’ve realised that actually to experience this artwork in this digital, immersive way is the most organic thing that could have happened – I’ve gone from being a little shy about it to being extremely enthusiastic to think that yes, we would have had his approval. Because it’s immersive, it’s inclusive, it’s bringing people into a world that otherwise would have remained dead on a canvas … Today, with artificial intelligence changing everything, we asked ourselves: what does it really mean to create? For Rambaldi, it was a blend of technique, imagination and soul. Alien Perspective aims to continue that dialogue, using new tools but with the same care.” At its core, they say, their creation is more than a tribute to a singular artistic mind: “It is an argument for the future of art: one that is active, inclusive, and infinite in reach.”