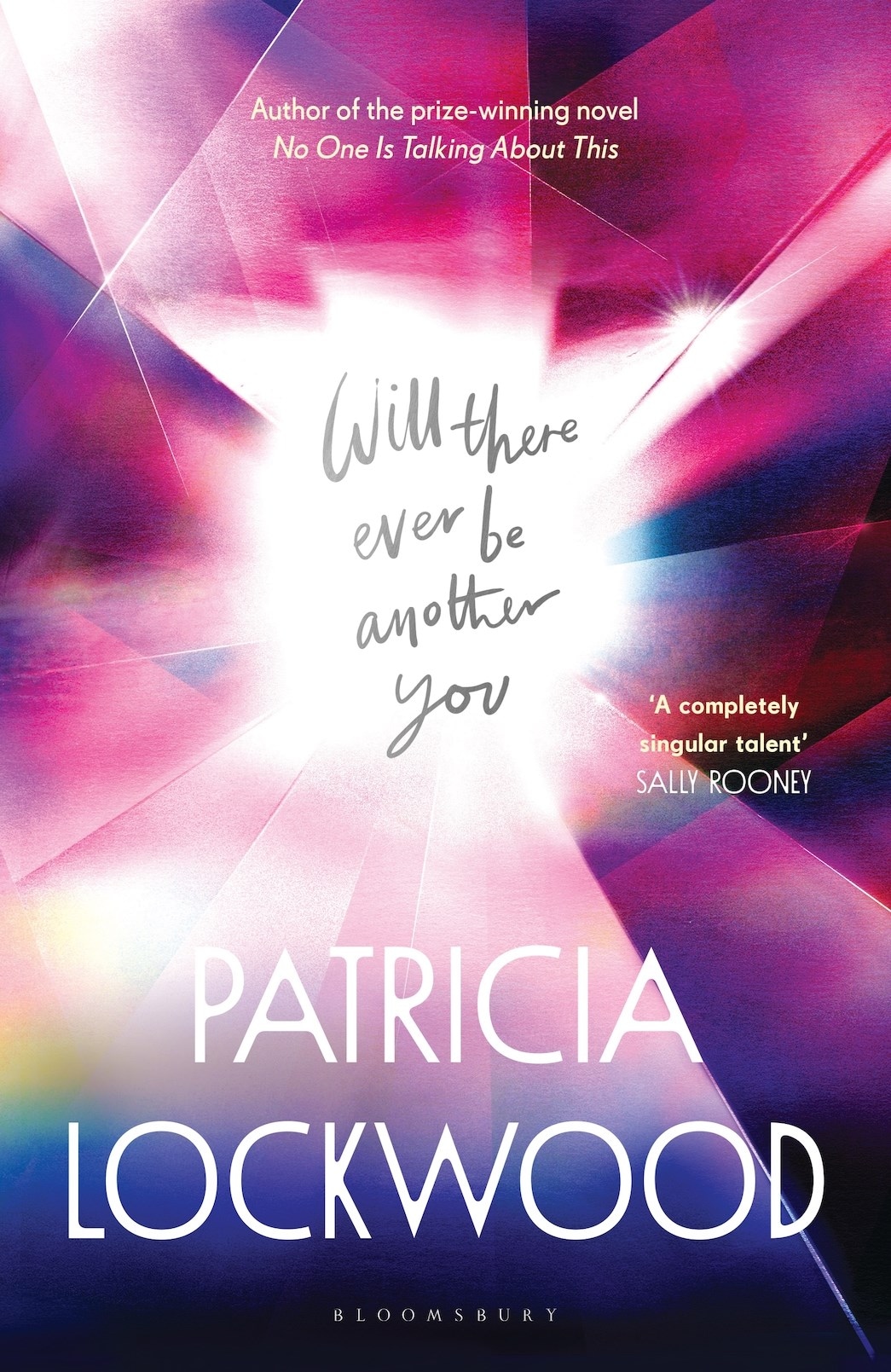

Patricia Lockwood is probably referred to as the voice of her generation more frequently than any other late-millennial author. Initially best-known for her poetry, she is also often referred to as Twitter’s poet laureate. Lockwood rose to fame by tweeting surreal sexts, the most well-known of which reads, “I am a Dan Brown novel and you do me in my plot-hole.“ Her breakout memoir, Priestdaddy, made her chaotic Catholic family famous and was named one of the top 100 books of the 21st century by the Guardian, and her debut novel No One Is Talking About This was the first to be shortlisted both for the Booker and the Women’s prizes for fiction. If the latter was a portrait of the inside of the internet, then Lockwood’s new novel, Will There Ever Be Another You, charts its decline and fall – and begins to ask what is next. The author turns her trademark finely tuned absurdism to illness and the pandemic in a highly readable fever dream that chronicles our unprecedented times. Formally, this novel is the author’s most experimental work to date; its disintegration charts the author’s – and society’s – loss of reason post-2020. But if a formally inventive pandemic novel is an alarming prospect, Will There Ever Be Another You sticks the landing, with persistent and distinctive humour.

Below, the author talks about her new novel, AI, and illness.

Marina Scholtz: So, you’re the high priestess of the internet.

Patricia Lockwood: Yeah, I am.

MS: There is this wonderful moment in Will There Ever Be Another You where you are giving a talk in Paris and you write “Twitter est mort“ on a whiteboard. How do you use the internet now? Where is the fun internet, and is the internet still a place where you create?

PL: Do websites even exist anymore? Recently, I have been talking with some people about this idea of ‘rewilding’ the internet, and I’m going to do my part. I’m going to have a website called normalwebsite.com and it’s just going to be journal entries and a photo sidebar and a visitor counter on the bottom right. Websites were where it was at, the little bites. There’s something about snack-sized pieces of people’s individuality. I want a chunk of someone. I want their whole hock in my mouth, and that’s what websites give us.

MS: Do you have a relationship with AI at the moment?

PL: Oh no. So what I do is, every couple weeks or so, I just go to the ChatGPT subreddit to see what the text looks like so I can arm myself against it. I want to know what people are saying about it. I want to know what it sounds like, because I’ve seen people, even people who I consider highly literate, get tricked. It’s not going to be me. I’m going to figure out what it sounds like so that I’m able to talk about it, but also to defend myself.

MS: The em dash thing is sad.

PL: I know. I’m like, fuck you. I’m so serious about that. We used that, it had a purpose – it was beautiful.

MS: You’re a writer who exhibits remarkably little self-doubt. You frequently do battle with literary giants in your critical work, and you rightly position yourself alongside them. How did you acquire this self-belief, and did it waver in the period the novel covers when you fell ill?

PL: I always say that I got a kind of positive megalomania from my dad. It was one of the early signs that I knew I was sick, that I really started to worry about other people encroaching on my turf. I have never thought about that in my life before. I worried about what people thought and what they said about me. I worried about reviews – I’ve never worried about reviews or anything like that, so I knew I wasn’t myself. And of course, I was releasing the book in the midst of this uncertainty. It was the most unpleasant experience to be in that place where you feel that other people are coming for your spot. It’s just an absolutely terrible, terrible experience to feel like people are fighting over slices of the same pie. I had that feeling for the first time ever and I didn’t like it at all.

“Let’s face it, who fucking understands their parents?“ – Patricia Lockwood

MS: Has it gone away?

PL: It has got away.

MS: Good. No one is coming for your spot because you are a freak.

PL: I am, and it’s also easier to have that self-belief when you are some sort of freak. Not to be like, “I’m so unique“, but some people are just a little bit weirder than others.

MS: In the novel, you briefly consider ghost-writing for Pamela Anderson …

PL: I did receive that email, but it was not like she was breaking down my door to write this. It was like, “Pamela wants to talk.“ I think that she said it could be like a Just Kids of the 90s, and I was really interested. Sitting in a hotel room with Pam Anderson would be very interesting to me.

ML: How do you capture the ridiculous with compassion? Especially when writing about family members, how do you pull it off? It is never cruel, never unkind.

PL: I think you get fidelity, and kinder, accurate portrayals if you reproduce the things that people say. I don’t do traditional character work where I’m sketching this character that I’m bringing to life, but I am telling you what they say, and I think that that is really building a puzzle that is more accurate than any sort of investigation that I’m doing into their minds. Let’s face it, who fucking understands their parents? Who understands their family? None of us do. They don’t have to be as weird as mine for it to be the basic situation of life that you will not understand these people, but you can put down what they say. You can put down how they treat you and what they do. For some reason, that forms an empathetic impact.

I’m also just not a very angry person. That was another way that I knew I was ill because I was very angry. I just thought, “This is not me.“ There were all these investigations in the book, through my past, where I thought, “I never got angry about this, do I need to be angry about it now?“ I think that was such an insulated, locked in time. A lot of people were thinking about their past more. I do think that you can sympathise with someone else’s body, even if you don’t sympathise with their beliefs. I think you can enter people through the physical plane. When I was sick, a lot of the time what was happening when I looked at you was, I’d be searching for something in you that was, I don’t know, pain, vulnerability – something that was difficult for you, and I’d be trying to identify with that. It was what I was experiencing, so I was looking for it in the world. At the same time that I was angry and confused and hated everyone, including my friends, I was also looking for that pain in people, to be connected.

Will There Ever Be Another You by Patricia Lockwood is published by Bloomsbury and is out on September 23rd.