Martin Sherman’s career took off in 1979, when his play Bent debuted at London’s Royal Court Theatre. This harrowing account of the way gay men were persecuted in Nazi Germany is now considered seminal, but at the time it was audacious and groundbreaking. In his deeply moving new memoir, On the Boardwalk, Sherman says that even the Royal Court’s artistic director was trepidatious. “Stuart Burge called several times to ask if I might consider removing the sex scenes,” he writes. “They made him very nervous. The dialogue was extremely graphic. Not everyone knew what two men did together.”

Sherman’s book covers the 40 or so years before Bent made him a success. He writes tenderly about growing up in a Jewish immigrant family in Camden, New Jersey, where his father was a charming narcissist and his mother was cruelly consumed by Huntington’s disease. For the first few decades of his life, Sherman mistakenly believed that he would inherit this progressive genetic condition, which gradually affects a person’s mood, movement and ability to communicate.

This terrifying prospect, combined with his unusual appearance – he was alarmingly thin and stricken with acne – contributed to his fragile self-confidence as he struggled to build a career as a playwright in 1970s New York. For many years, Sherman was an observer on the fringes of culture, celebrity and growing social change. In the book, he writes about stumbling into the Stonewall Riots of 1969 – at the time, no one realised they would catalyse the modern-day gay rights movement – and working with eminent figures like Mama Cass and Hollywood legend Rosalind Russell.

We meet at a café near his home in an upmarket but unstuffy part of central London. Sherman moved here 45 years ago and never left. At 86, he is sharp, self-assured and widely respected: his other notable works include 1999’s brilliant one-woman play Rose and 2005’s hit Judi Dench film Mrs Henderson Presents. “After I wrote the book, I realised that I needed to start a new life in a place where the old life didn’t exist, where that dark shadow of illness was non-existent,” he says. “The shadow was gone, but I knew it wouldn’t ever really leave in the eyes of the people who had seen it around me.”

Below, Martin Sherman elaborates on his new memoir.

Nick Levine: Have you been wanting to write a memoir for a while, or did you need a little cajoling?

Martin Sherman: No, I never thought about writing a memoir. I used to tell people stories about my father, and they’d say: “You’ve got to write that as a play.” I didn’t want to do that because I’d have to go through it every day in rehearsal and then see it on stage every night. And then one day I thought, “Well, maybe I can write a little memoir.”

I thought it would mainly be [about] my childhood because I didn’t really think there would be anything interesting after that. But then I discovered that there was a lot more to write about, which really surprised me, and that I enjoyed doing it. I thought it was going to be extraordinarily traumatic, but it wasn’t. It’s traumatic now.

NL: Why is that?

MS: Because people are going to read it. When I was writing it, it never really struck me that anybody would be reading it, so I felt free to say whatever I wanted. But now I think, “Oh my god.” It’s like being naked in a room filled with strangers.

NL: After the book moves beyond your childhood, it becomes a portrait of a struggling artist. But even before your breakthrough with Bent, you got to work with all these incredible people – you brainstormed sitcom ideas with Rosalind Russell; you worked on a TV special for Mama Cass.

MS: But I was working with them in a totally nondescript and anonymous way. It’s great for the book, because it gives a wonderful view of those people. With Rosalind Russell, they just needed some schlemiel who could go in and waste time with her for a couple of weeks. And with Mama Cass, it was ridiculous. I was in a writer’s room and literally one word of mine ended up on her TV programme. I can’t really think of it as a writing experience, but it was a fascinating experience about life. I was on the edges [of showbusiness] – I think there are a lot of people in that position, who encounter these famous people, but just slightly.

NL: The way you write about your younger self – a person with no confidence in how they look, who’s haunted by the prospect of serious illness – is just heartbreaking. Did revisiting those years give you more empathy for yourself at that time?

MS: I suppose seeing it again, I understood how really difficult it was. But I knew that [already]. And I suppose that became a reason for writing it. If you can have those difficulties, and you can live with them and through them and past them, then it becomes a story worth telling others. People think I exaggerate how thin I was. Actually, I was a malnourished child, but people never mentioned it. I talk [in the book] about an incident in a hotel in Atlantic City where a woman, very cruelly, said to my mother: “Don’t you ever feed him?” That was the only time anyone ever said anything, but it was in keeping with the silence around my mother’s illness. I lived in the most powerful volcanic denial, but there are advantages to denial. If I had been completely conscious of how I looked, it would have been unbearable.

“If you can have those difficulties, and you can live with them and through them and past them, then it becomes a story worth telling others” – Martin Sherman

NL: The book ends with Bent becoming a hit on Broadway and in the West End in 1979. It’s been produced many times since then, all over the world, but do you think it’s due for another London revival?

MS: We’ve been trying to do one for the last couple of years, so hopefully it will happen in the next year or two. I’ve had a lot of discussions with Sean Mathias, who would direct the revival, and he has some really creative concepts of how to do it now, because I think it has to live in a different time and be done slightly differently. But I don’t want to say too much.

NL: Generally speaking, what’s your stance on whether straight actors should play queer roles? It’s a debate that doesn’t seem to be going away.

MS: I think straight actors, if they have the right qualities, should be able to play a queer role. And equally, queer actors should be able to play a straight role. I say that because I grew up at a time when if you were a queer actor, you just weren’t cast in a straight role.

NL: In the book, you write about how bold it was for Richard Gere, as a straight leading man, to star in the original Broadway production.

MS: It was tremendously courageous, but he immediately wanted to do it. And he’s been called “queer” ever since, but he didn’t care because – and this is the key – he is totally comfortable in his sexuality. I think that’s probably the answer to your question about whether straight actors can play queer roles. If they’re comfortable in who they are, yes. And equally, if a queer actor is comfortable with who they are, they can play straight.

NL: You spotted this question in my notes earlier, but what do you hope people take away from the book?

MS: How important it is not to give up. I suppose what makes it a valuable story is that I didn’t have success until middle age, because most success stories are about fairly young people. It’s easy to think that by the time you’re in your thirties, if it hasn’t happened yet, it’s not going to happen. But that is not necessarily true. When I was in my twenties and thirties, I wasn’t someone you would look at and say: “Oh, that guy is destined to have success.” You wouldn’t have said that at all! So I think that’s an important message to share.

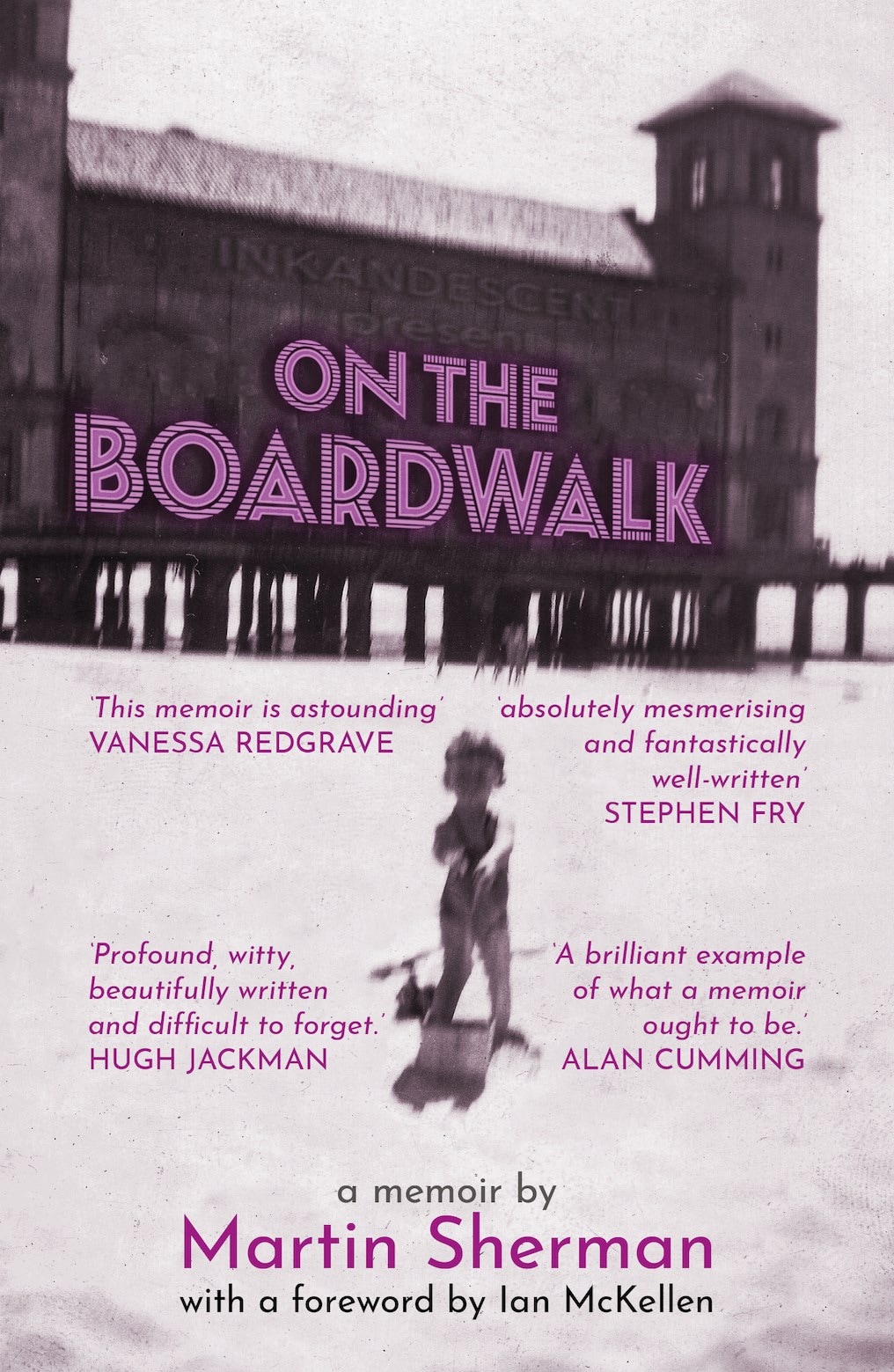

On the Boardwalk by Martin Sherman is published by Inkandescent and is out now.