The Design Museum’s new exhibition highlights the cultural legacy of Blitz, the Covent Garden nightclub that launched the careers of Boy George, Stephen Jones and more

Though it only ran for 18 months, Covent Garden’s Blitz club remains a cultural phenomenon. The weekly night was launched by musicians Steve Strange and Rusty Egan in 1979, and has been credited with cementing the careers of a host of famous names, from Boy George and Spandau Ballet to designers Stephen Jones and Michele Clapton. Following recent 1980s London homages including Leigh Bowery! at Tate Modern and The Face Magazine: Culture Shift at the National Portrait Gallery, the Design Museum opens its own celebration of this explosive creative era.

Blitz: The Club That Shaped the 80s brings together over 250 archive pieces, covering fashion, music, film, art and design. The Design Museum's curatorial team worked closely with the original Blitz kids, speaking with around 100 people embedded in the scene. For curator Danielle Thom, this moment in London history marked a “sweet spot” – a pre-digital era that is also “not ancient history”. As such, the show is both novel and nostalgic, capturing a scene that was quite unlike anything that came before it.

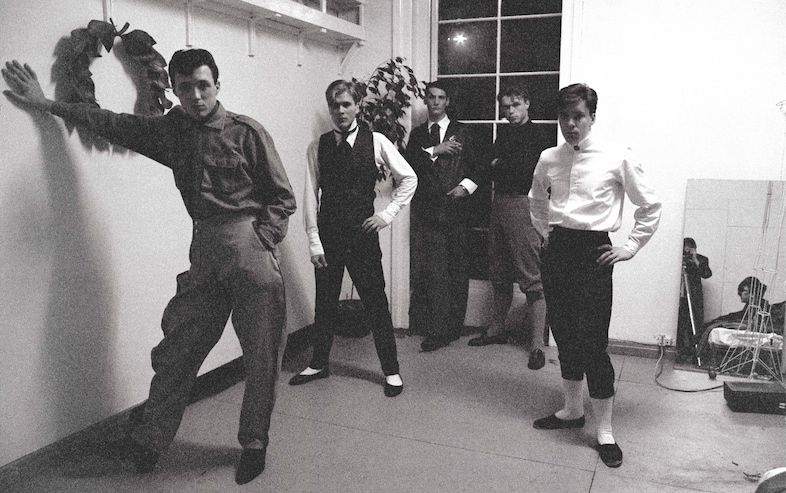

The 70s punk scene, which many of the Blitz kids had been part of, was evolving into something more commercialised by the end of that decade. Many Blitz regulars retained punk's DIY ethos and disregard for conventional taste while imbuing their looks with more opulence and glamour. The media quickly jumped onto the burgeoning scene as an epicentre of New Romanticism, though the Blitz kids would not necessarily have all defined themselves in that way.

“They created so much out of so little,” says Thom, noting that many looks were put together from items sourced in charity shops and jumble sales, or handmade by resourceful students. “The majority of Blitz kids came from working class or what you might call lower middle-class backgrounds. A lot of them lived in squats. When they joined the scene, they didn’t have existing professional networks. But because of their lack of resources, they had a lack of restraints in other respects.”

Unlike Covent Garden’s commercial landscape now, the Blitz club ran pre-development. The fruit and veg market had recently closed and young boutiques were starting to spring up. The club night happened in an existing wine bar, also called Blitz, with Strange drawing attention from new magazines such as The Face and i-D – many of their writers were regular fixtures, amplifying “what was essentially quite a niche night”.

While music was a central aspect of the club, its visual expression was just as important. “The Blitz scene epitomised and catalysed the shift from fashion to style,” says Thom. “It’s a shift from that which is hierarchical and top down, to that which is idiosyncratic, individual and from the streets up. That emphasis on individualism is really interesting. On the one hand, the Blitz kids operated as a collective, they collaborated. At the same time, there is this emphasis on individuality and this is of course the dawn of Thatcherite Britain and the shift towards the individual versus society. There is a tension which was very interesting.”

The exhibition celebrates not just the big names but everyone who shaped Blitz. One room explores the impact of music videos, still in their infancy and propelled by the launch of MTV and acts like Queen. “The music video was arguably one of the most important vehicles for Blitz culture,” says Thom. “The acts that emerged, with their emphasis on visual identity, were well placed to dominate the music video revolution.”

Many of the clothes and memorabilia on show have been unearthed from attics and private collections, rather than museums, highlighting Blitz’s DIY legacy. An ensemble comprising a robe and chemise dress designed by BodyMap’s David Holah for makeup artist Lesley Chilkes is covered in cigarette burns and wine stains. There are also items from early student collections. “Some went on to become well known, like Stephen Jones, but others made a splash at the time and didn’t go on to the big-name career that their talent might have justified.”

The curators are keen to show the full range of looks that were presented at Blitz. “It wasn’t this monolithic culture of New Romanticism. It wasn’t all frilly shirts and sweepy fringes. There was a reasonable element of diversity in style.” Clothing is shown alongside vintage magazines and musical items: Spandau Ballet’s Gary Kemp has lent his first synthesiser, used to perform the band’s debut album and played at Blitz. “It’s a wonderfully time-period-specific example of music technology. It symbolises this shift towards the electronic. The Blitz was by no means solely responsible for this, but it helped precipitate it.”

Thom mentions that finding one definitive view on the club amongst the urban myths is challenging – instead, there are “as many versions of the story as people telling it.” An anecdote about Steve Strange turning Mick Jagger away because his outfit was too conventionally rock and roll, for example, was heard by many people but seemingly witnessed first-hand by no one. But in retrospect, Blitz’s legacy reflects certain aspects of its time. A generation that didn’t grow up in the direct shadow of war, Europe, and a renewed connection with Germany, was opening up. Bands like Kraftwerk, as well as German art and cinema, had a strong influence on the Blitz scene, which looked to the tail end of Weimar and cabaret culture for inspiration.

The club also existed in a window between the decriminalisation of homosexuality and the AIDS crisis. “The Blitz scene was an important moment for queer visibility. It was on a trajectory that fed into Taboo. While it was never explicitly a gay club, it had a significant following among gay men and women. At the time, there wasn’t the language and framework around trans identity, but there were a lot of gender fluid individuals at the club. They attracted curiosity and yes, some mockery for how they presented themselves and their implicit queerness, but they also had a lot of cultural power.”

There is a sense of loss in revisiting such heady creative moments that feel out of reach in today’s cities. “University education was free, inner London was cheap to rent and travel in, a lot of Blitz kids lived in squats,” says Thom. “The dole, as it was then, wasn’t by any means generous, but it was closer to the cost of living than today’s equivalent. There were certain economic and structural circumstances which meant the Blitz kids could be the Blitz kids. Those circumstances don’t exist any more.”

Blitz: The Club That Shaped the 80s is on show at The Design Museum in London from 20 September 2025 – 29 March 2026.