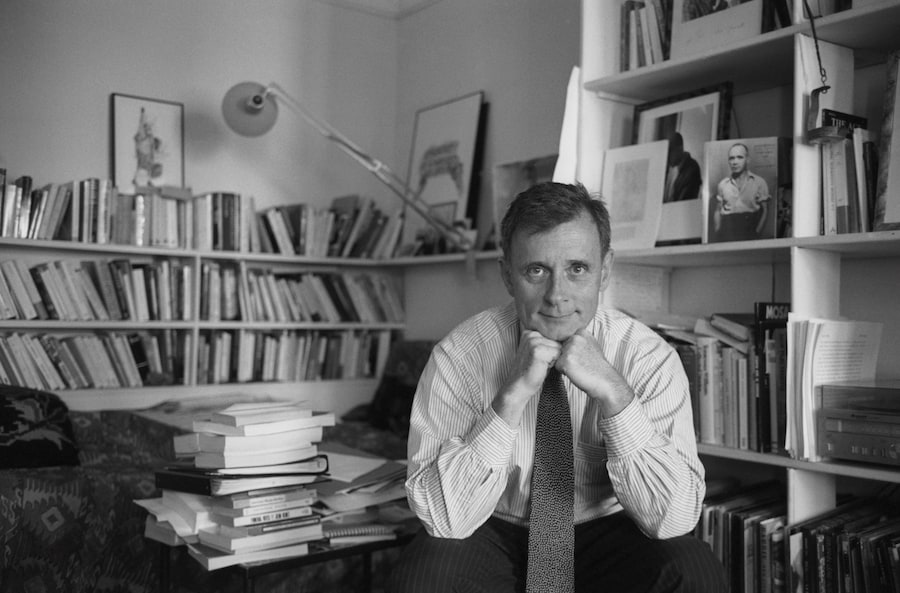

Following his death earlier this month, we offer a five-point guide to the American writer’s life and work, from The Joy of Gay Sex to his biographies of Proust and Genet

Edmund White was a prolific writer. In a career spanning five decades, he wrote about art, politics, and queerness with an endless curiosity, constantly challenging not just readers, but himself. After his death he was described in a tribute as the “patron saint of queer literature,” leaving behind a body of work that, until the very end, was constantly pushing the boundaries of how we might understand the relationship between literature and queerness.

Whether in his trilogy of autobiographical novels – A Boy’s Own Story, The Beautiful Room is Empty, and The Farewell Symphony – his biographies of literary titans like Marcel Proust and Jean Genet, or his writings about sex and desire, White revealed the multitudes that queerness contains.

Here, find a five-point entry guide to the work of Edmund White.

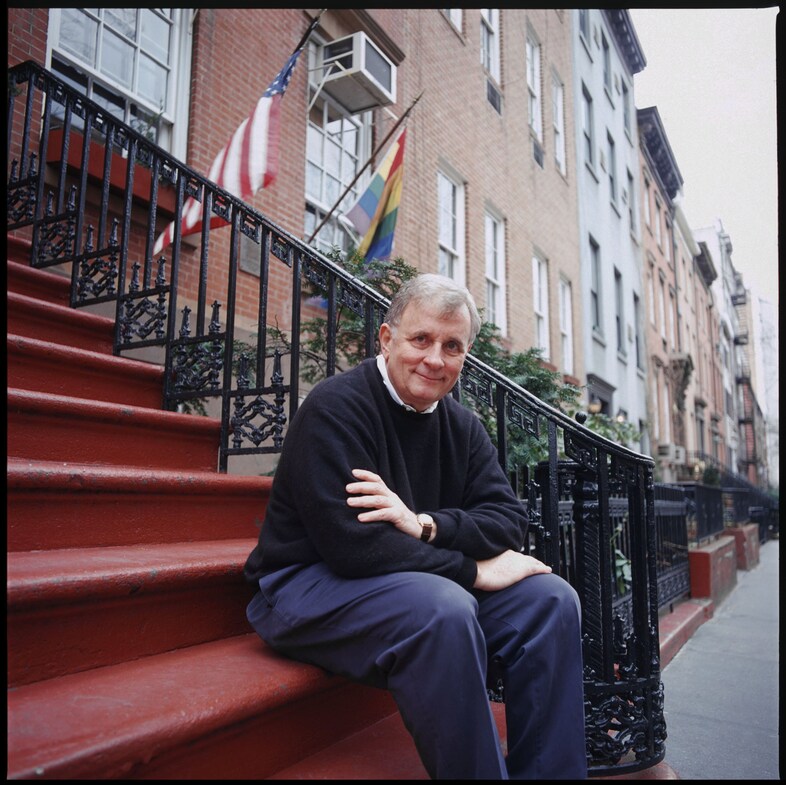

1. White was there at the Stonewall riots

In 1969, White was at the Stonewall Inn when the riots began, a pivotal moment in the modern movement towards gay liberation. White would later remember this as what “may have been the first funny revolution,” but more than that, as a sign that “gays might constitute a community rather than a diagnosis,” a shift away from the medicalised way in which homosexuality was conceived at the time, into a group with a political agenda, and with a culture unique to itself. It’s no wonder that so much of White’s writing in the wake of Stonewall would aim to capture the culture, nightlife and desire of this community, whether in fiction or non-fiction.

2. The Joy of Gay Sex changed the ways we understand desire

With a title as brazen as The Joy of Gay Sex, it might be tempting to think of White’s 1977 tome, co-authored with his then-therapist Charles Silverstein, and the book that launched White into the wider literary consciousness. And while the book naturally offers chapters on blowjobs, rimming, and sex positions, it also casts an eye onto the wider concerns of the queer community, whether sexual or political. The Joy of Gay Sex features digressions on sexual dynamics that are often seen as uniquely queer, like cruising, while also considering the realities of coming out, and queer politics. Inevitably, and tragically, The Joy of Gay Sex has become something of a time capsule, a way of understanding what gay communities (and gay sex) looked like before the Aids crisis.

3. His autobiographical novels offer a first-hand account of queer history

From 1982 to 1997, White wrote a series of novels charting the way in which a young male character comes of age and begins to understand himself and his queer identity. A Boy’s Own Story, the first in the trilogy, begins with White exploring furtive adolescent desire, as his protagonist grapples with an understanding of his attraction to men, while trying to still pass it off as a phase. As the trilogy goes on, the protagonist (seen as a version of White himself) grows up and sees queer community and politics form; The Beautiful Room is Empty ends with the Stonewall Riots, and the final novel, The Farewell Symphony, as it must, recounts the ways in which the Aids crisis ravaged the queer community.

4. White’s literary biographies challenged the mythological writers of the past

It’s no secret that writers are prone to self-mythology. And throughout his career, White wrote biographies that grappled with the mythologies of some of the most acclaimed and important modern French writers: Arthur Rimbaud, Marcel Proust, and Jean Genet. In perhaps the most well-known of his trio of biographies, White places Genet’s queerness front and centre when he interprets the life and work of the infamous novelist. While responses to the book argued that White might have cast too narrow a net on Genet’s body of work, his willingness to embrace Genet’s queerness allowed people to see him in a new light.

5. Above all else, White was a reader

In 2018, White’s memoir/essay collection The Unpunished Vice was published. In it, White reflects on his life through the act of reading; reflecting on some of his favourite books, which include everything from Nabokov’s Lolita to the 1930s Henry Green novel Nothing, which White said he returned to once a year. Through his expansive library and impossibly well-read sensibility, White offers a portrait of himself through the books that fascinated him over the years. Through the light, conversational tone of The Unpunished Vice, White offers not only the intimacy that comes from seeing someone’s library, but also a connection with the man himself – the kind of connection that would recur throughout his writing and that, even after his death, we’re able to hold onto.