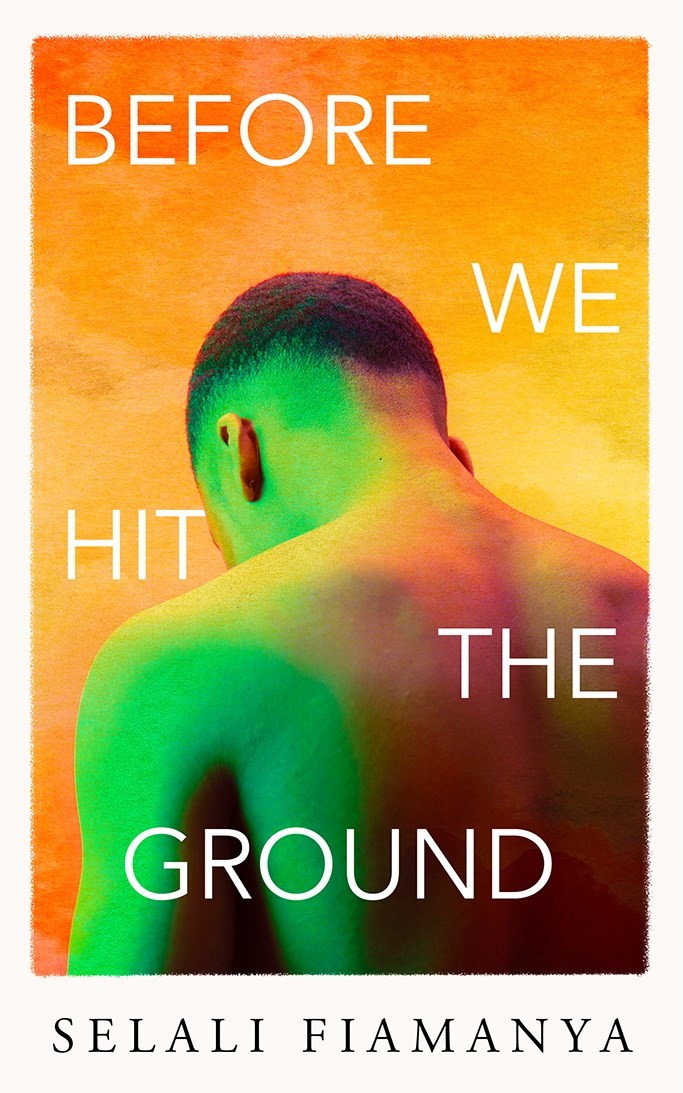

Before We Hit the Ground, the beautiful debut novel from Selali Fiamanya, captures the elusive nature of human connection. Fiamanya’s multi-generational story follows Abena and Kodzo, an aspirational young couple from Ghana, as they build a new life in Glasgow from the 1980s to the near-present. Their daughter Dzifa breezes through school and social situations, or at least appears to, but their son Elom is more introverted and inscrutable. This family clearly loves each other, but can’t always show it.

Fiamanya, who was born and raised in Glasgow, but also spent a couple of years in Ghana’s capital Accra, built his novel from character sketches he began writing a decade ago. The book’s overarching narrative came into focus later, when he was helping his parents to clear out their attic. “That got me reflecting on this feeling of archiving a life, particularly the life of people who’ve moved here from another country,” Fiamanya says. “And that led me to a question I could structure a book around: Why would elderly parents be excavating their life like this? Usually kids clear out the family home when their parents die, so I flipped that on its head: in this story, it’s the son who dies.”

Elom’s death is revealed in the opening chapter. Fiamanya then spools back to piece together how every family member develops over three decades. Abena overcomes tacit racism to build a career as a pastry chef, while Kodjo grapples with religion and mental health issues. Dzifa gets into Oxford, then becomes a junior doctor – an experience Fiamanya knows about because he’s currently training as a GP. “I’m lucky that I don’t take my job home with me,” he says. “I’ve enjoyed having this other life where I get to pour my creative energies into a book.”

As the novel progresses, Elom comes to the fore. We see him grapple with the realisation that he is gay, then enter into a relationship with Ben, a primary school teacher who’s charming but manipulative. “It’s for readers to decide whether Ben is a villain,” Siamanya says teasingly. But ultimately, Before I Hit the Ground is a story about learning to accept love on its own terms. “Part of being loved is meeting other people’s needs and having them meet your needs. But sometimes, when a person isn’t able to meet your needs, that doesn’t mean they don’t love you or that they haven’t tried to show it,” Fiamanya says.

After finishing his book, you’ll almost certainly want to phone someone close to you. Here, Selali Fiamanya discusses how he wrote his moving meditation on love, family, heritage, queerness and purpose.

Nick Levine: Is each of the family members struggling, in their own way, with what society expects them to be?

Selali Fiamanya: I think of it as a book about agency. I don’t like the word “self-realisation”, because it sounds very Instagram self-help. But I’m asking questions like: “How do you come to a sense of knowing what you want from life? And how do you actually get it?” Elom struggles to understand what he wants, whereas [his mother] Abena always knew what she wanted but had the odds stacked against her.

I think a lot of us feel an inner tension in figuring out which elements of society’s expectations we want to live by, and which ones we want to reject. Sometimes it’s a question of how much you’re willing to sacrifice in order to reject those expectations. Because it’s always easier to do what society expects of you.

NL: Which of the characters did you find hardest to write?

SF: Definitely Dzifa, because what I was trying to do with her was the most subtle. Abena is a woman burdened by the expectations of a misogynist society, so there’s quite a lot of other writing [out there] that I could lean into. But I didn’t really feel there was anything I could lean into with Dzifa. She felt quite close to myself in a way, so I had to excavate some of my own insecurities and thoughts about the world. And some of those things were difficult to face.

“I think a lot of us feel an inner tension in figuring out which elements of society’s expectations we want to live by, and which ones we want to reject” – Selali Fiamanya

NL: When one of Dzifa’s friends says she has so much “initial charisma”, then suggests she doesn’t really fulfil it, it’s absolutely savage.

SF: I’m glad that comes across. Do you know Lianne La Havas? She has a song called Paper Thin where she sings about “slipping in and out of such confidence and overwhelming doubt”. I think that really speaks to what Dzifa is going through.

NL: What did you want to convey in the scenes where Elom comes out to his parents? He’s clearly craving an overt show of support from them, but they think they’re doing the right thing by not making a fuss.

SF: What I wanted to explore in those scenes, and the characters’ [subsequent] reflections on them, is whether it’s enough that these people love each other. Or actually, should certain people be blamed for getting it wrong? It’s something I think a lot about as a queer man of colour. Like a lot of people, I come from a family background where the chances of having my parents join me at Pride are very low. Some of my white British friends have had completely different experiences of coming out, so their expectations are very different too.

The difficulty I’ve found is that you can fall into this dynamic of thinking that your parents are ‘bad’ or ‘homophobic’ for not giving you what you need. There’s some truth to that, but I don’t think it’s that simple. And it doesn’t mean you’re not appropriately proud of your queerness if you meet your parents and culture in a different way. So this [part of the book] is for the queer Muslims, and queer people from African or Caribbean backgrounds, who are trying to reconcile their sexuality with their family and faith. For them, it’s not as simple as asking: “Do I have total acceptance or not?”

NL: What made you include the cruising scene? I like that it’s quite matter-of-fact: just something that Elom does in the moment to meet his needs.

SF: I mean, he’s horny but he’s also searching for some kind of connection. I don’t want to decry cruising as something that isn’t risky and dangerous and illicit, because in some cases it is. But in this sex scene, the stranger who meets Elom in a dark forest in the middle of the city actually respects his boundaries and shows him care and tenderness. He doesn’t continue fucking him when it becomes clear that Elom isn’t into it. I felt it was very important to demonstrate that aspect of cruising.

“I come from a family background where the chances of having my parents join me at Pride are very low. Some of my white British friends have had completely different experiences of coming out” – Selali Fiamanya

NL: Have you been surprised by any of the early responses to the novel?

SF: Well, I wanted to be quite confident in writing this book from the Ghanaian British perspective: you know, not translating words or worrying about how things might be received. But at the same time, there was always this doubt about how it might resonate with people who aren’t from that culture. And so my heart’s been really warmed to see people from all backgrounds feeling such a connection with these characters. It really shouldn’t surprise me that literature has the ability to reach across cultures in this way. That’s my experience of literature, and why I love it, so it’s been really nice seeing it happen with my book.

Before We Hit the Ground by Selali Fiamanya is published by The Borough Press, and is out now.