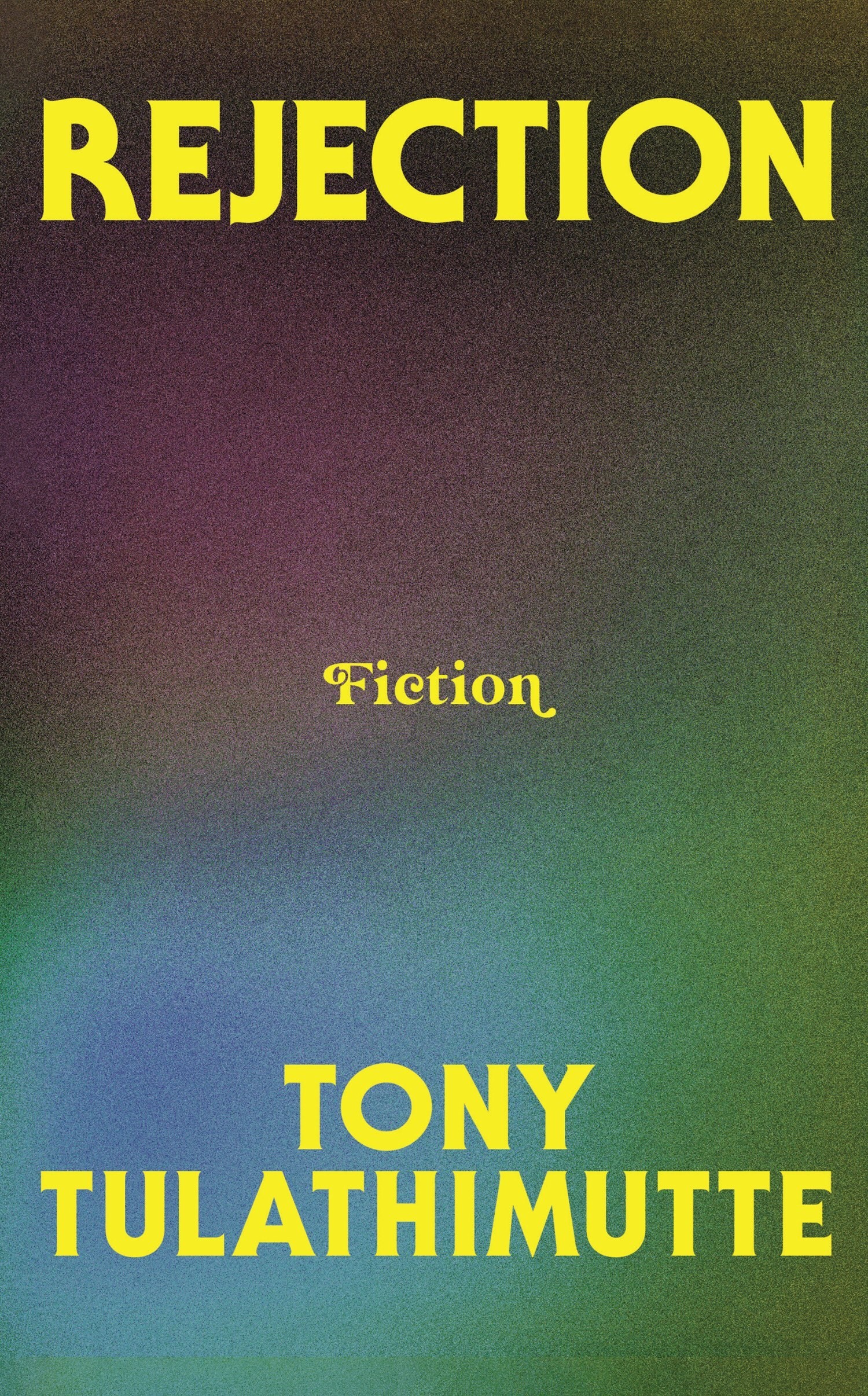

Rejection is something we’re all familiar with, but in a hyperconnected world, it happens on the internet’s global stage. Whether it’s a pointed use of a full stop or a correction on a regularly used forum, we are open to the slights of others constantly. Alongside these micro-rejections that leave bruises and welts on our egos, there is also the matter of romantic rejection, platonic rejection, creative rejection and community rejection.

Tony Tulathimutte’s sophomore novel, Rejection, follows the ensuing downfalls of each of its six extremely online characters. Dealing with rejection in all its forms, each character finds themselves increasingly isolated. From the opening tale of a “woke” single man desperately seeking female companionship to an internet sleuth who refuses any racial or gender identifications, Rejection refuses to soothe its audience, instead inviting the reader into the many hell mouths shaped for the terminally online.

The internet’s place in contemporary fiction is well established, but few authors venture beyond the easy comparison of reality and our overly curated digital image. Tulathimutte explores the nooks and crannies of the internet’s infinite warrens, switching terminology and tone to reflect its dialects. From self-aggrandising Reddit posts to extreme pornographic fantasies, vacuous Whatsapp chats to sickeningly sincere Instagram posts, Rejection succeeds in documenting the minutiae of online life.

Below, AnOther spoke with Tony Tulathimutte about how Rejection came to be.

Billie Walker: Rejection is an inevitable part of life but also a potentially positive and transformative experience, although it negatively impacts every single one of your characters. Why?

Tony Tulathimutte: What people expect out of books about rejection and social crises like this is self-help. If you go and look up “rejection” on Goodreads or Amazon, most of what you’ll find is either self-help or Omegaverse fiction. I think I have written a book that does the opposite – of self help at least. Someone at my publishing house called it a book of self-harm.

BW: There are very few contemporary authors that write the internet well. How did you succeed?

TT: You don’t try to embody it in any literal sense.People know what it’s like to put a shirt on, so you don’t need to say, I thrust my arm up one sleeve and then another before pulling my head through the centre. In the same way, portrayals of the internet can get bogged down in describing somebody scrolling in bed with the light shining on their face. It sort of misses the point of being online for long stretches of time, which is a feeling of timeless, spaceless immediacy. You feel like your mind has kind of been chucked through the glass, and you’re experiencing content in this unmediated way. Everything is designed to immerse you like that.

BW: People used to think of the internet as something that offered us a sense of community. But you’ve referred to it as a “cursed mirror”. How do you feel about how we interact with the Internet?

TT: Another thing about writing about the internet is it often concerns itself with uses of the internet that everyone is familiar with. “I totally know this kind of post. I recognise that.” But one of the great allures of the internet is that it allows you to do a lot of freak shit in private. So the answer really is that most people don’t know how most people use the internet. If you’re online long enough, you’ll get these glimpses of incredibly niche communities that you would have never guessed existed, but that constitute the majority of somebody’s internet use. So it’s a fool’s errand to try to make sweeping pronouncements about how everyone does it, in spite of large tech companies’ attempts to genericise the way we use it. The universal internet experience is an illusion.

“You feel like your mind has kind of been chucked through the glass, and you’re experiencing content in this unmediated way. Everything is designed to immerse you like that” – Tony Tulathimutte

BW: What does the title say about the book?

TT: The book is called Rejection, so I think right up front, you’re oriented in a thematic way. It’s fair to anticipate an arc towards conciliation or radical alterity suggesting a way out, but that’s just not the kind of book I wanted to write. Again, I think with the understanding that most of the literature out there is already self-help, I wanted to go in the other direction. There is something comforting about just being able to forthrightly acknowledge that rejection is very painful, without sugarcoating or minimising or giving tips and tricks to alleviate it. Sometimes people just want to have their pain recognised, especially online.

BW: You've mentioned before that Calvin Kasulke’s Several People Are Typing was an influence. Are there any other novels that inspired you?

TT: Calvin was a student of mine! As for other books, there’s Alasdair Grey’s 1982, Janine, and Dennis Cooper’s The Sluts, which is oddly not often brought up as an Internet novel but it’s actually just incredibly ahead of the curve. If more people read it I don’t think they’d call my book particularly shocking. I have been finding in a lot of the US reviews a sort of recoil or distancing. Where people are like: “Don’t recommend this book to anybody, don’t read it in public, wear head-to-toe PPE while you’re reading it.” And then give it five stars. It really speaks to how contaminating people feel the condition of being socially outcast is. I think I read a study somewhere about how children will exclude other children who they perceive to be unlucky. For decades now there’s been a consolidated push to make consumption, including cultural consumption, the basis of identity. When that is the case, then of course you don’t want people to get the wrong idea by admitting you consumed this unethical art uncritically or whatever, which would make you seem suspect. I recently saw someone online call this the Cooties Theory of Art, which really is the best way of putting it.

BW: You preempt your creative rejection in the novel, but the critical response has actually been overwhelmingly positive. How does it feel?

TT: It’s not an easy subject to feel triumphant about. I’m really glad that people seem to be enjoying the book. I don’t think it has fixed anything about me. I say this not to be ungrateful or to downplay the simple ego gratification of having your work written about in positive terms. It’s just to say that it wasn’t intended as therapy, and it didn’t achieve the effects of therapy either. For the most part, when you write about unpleasant stuff it’s almost anti-therapy, in the sense that it’s an elevated form of wallowing that prevents you from moving on.

Rejection by Tony Tulathimutte is published by 4th Estate, and is out now.