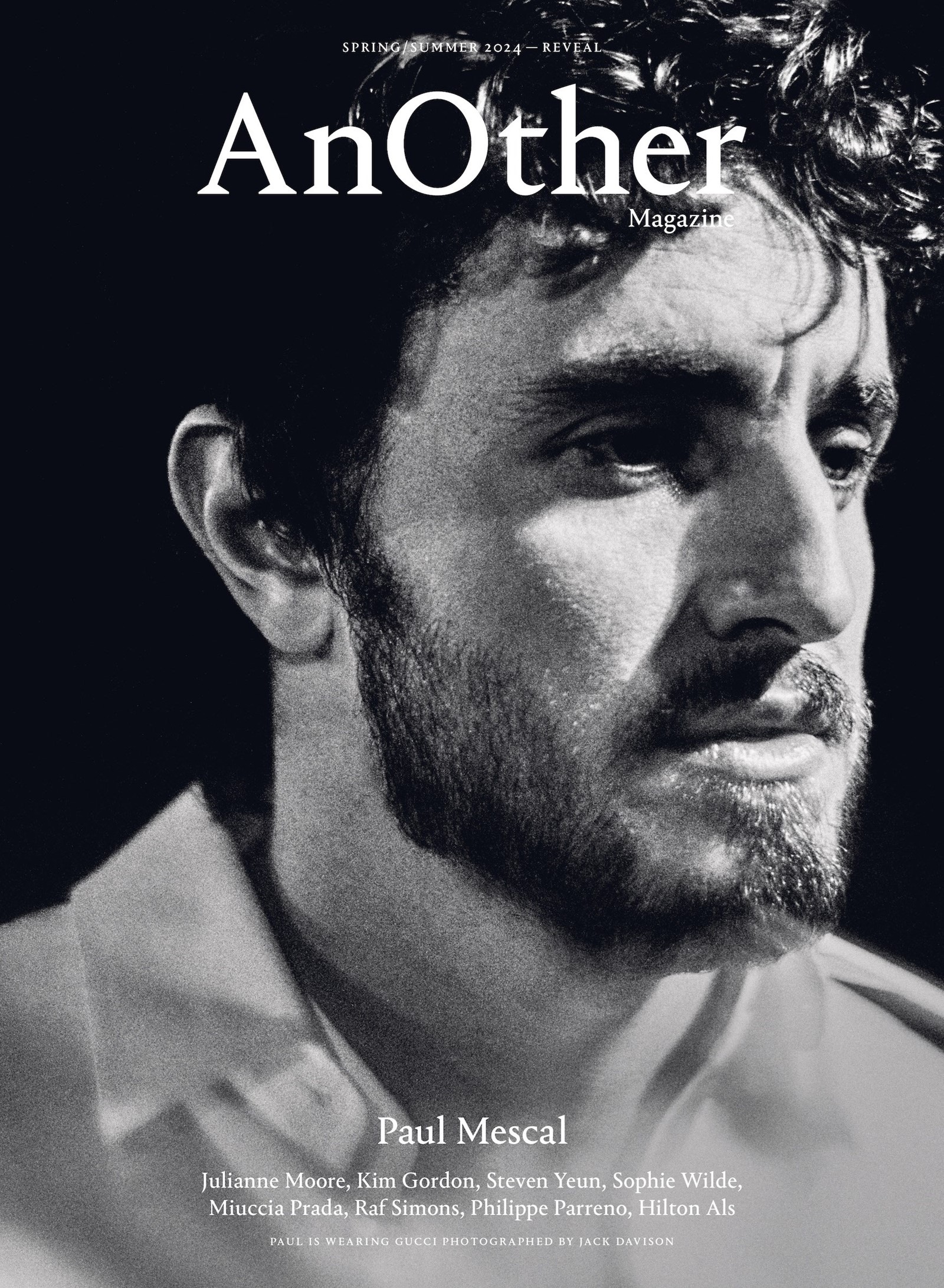

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine:

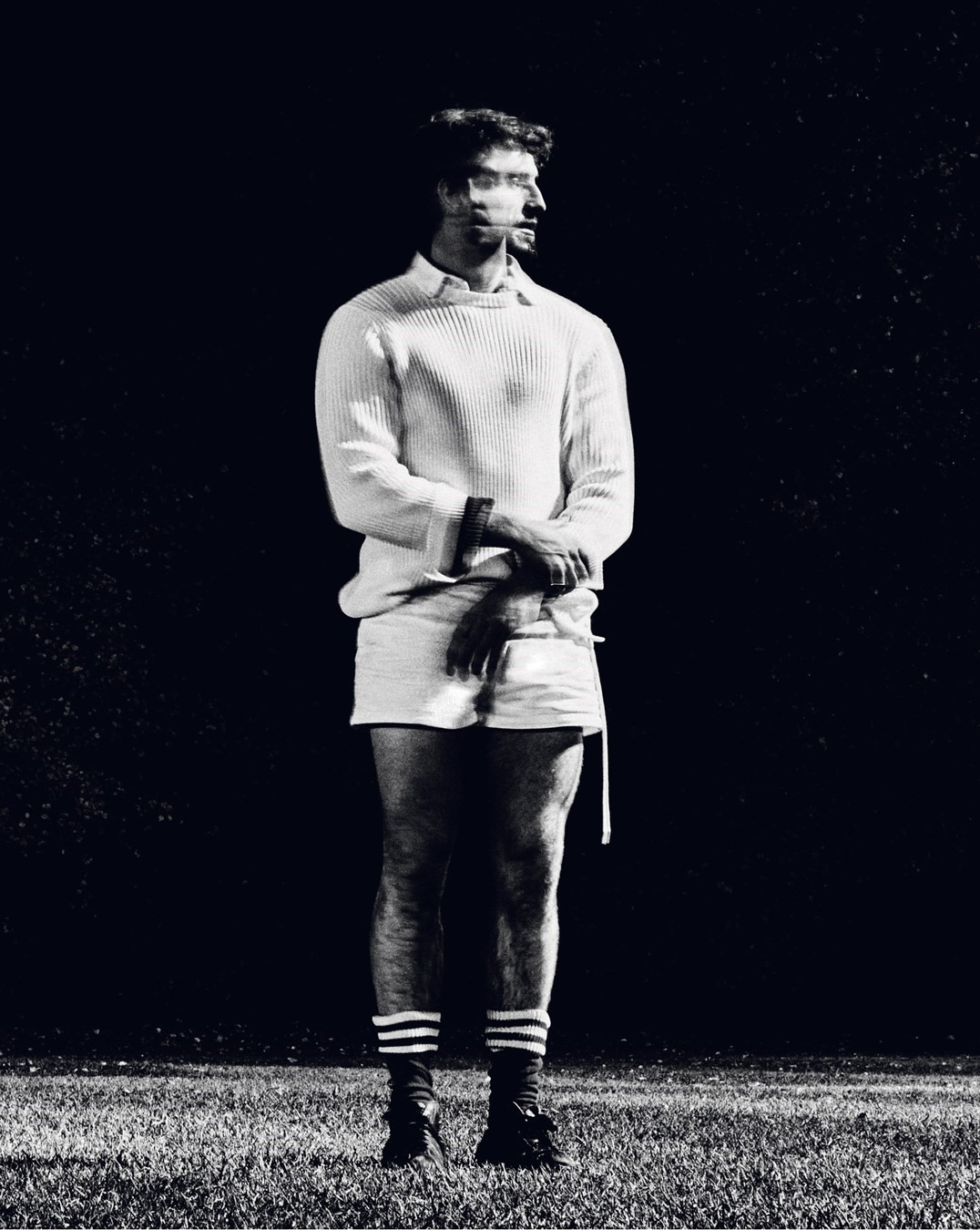

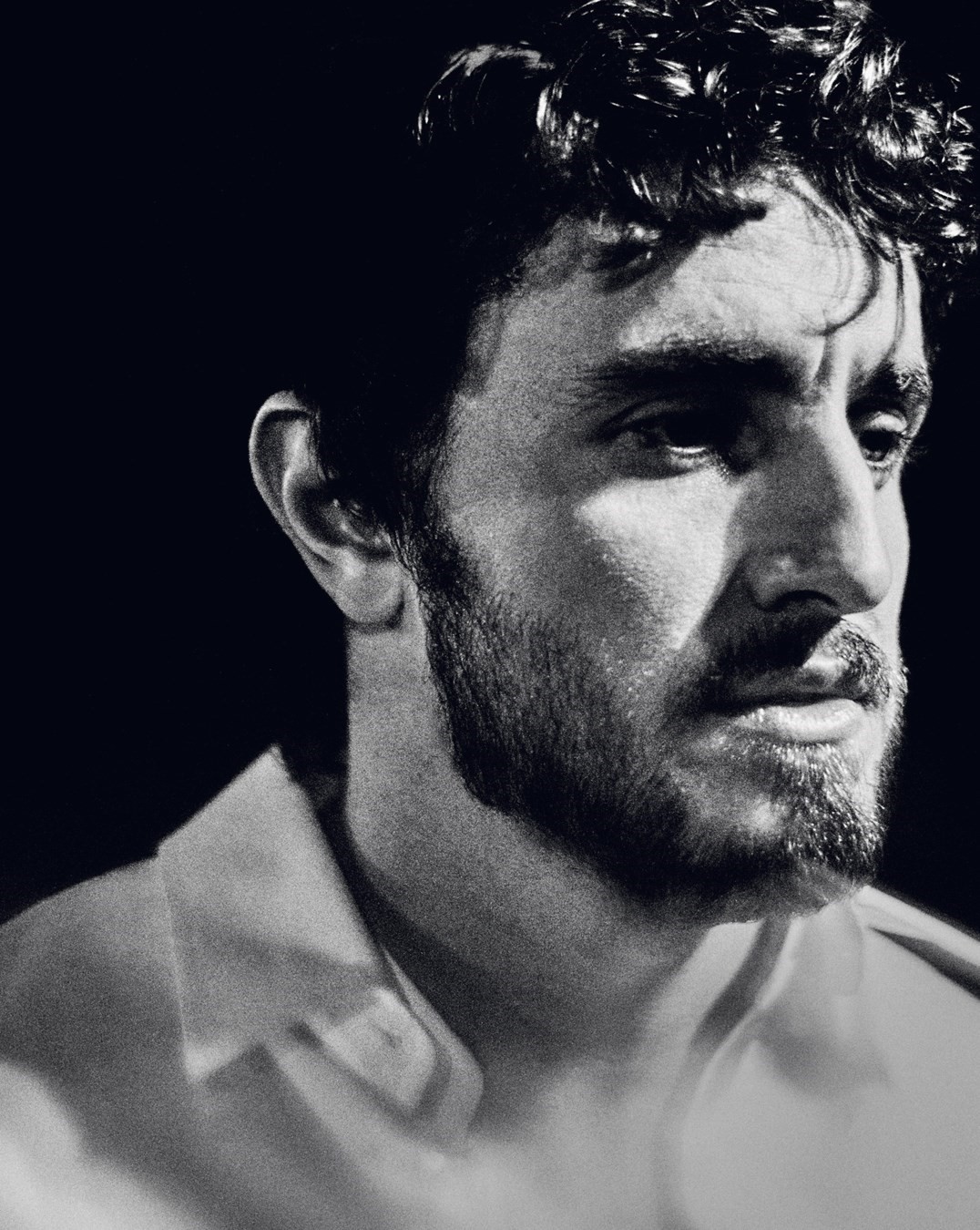

With three years of theatre in Dublin under his belt, the actor Paul Mescal only came to mainstream attention in April 2020 when he made his television debut in the hit Lenny Abrahamson-directed adaptation of Normal People, the best-selling novel by Sally Rooney. It was the most-streamed series on the BBC that year and made Mescal a household name – his role as awkward, school-age Connell earned him an Emmy nomination and a Bafta for best leading actor. In the four years since, a series of impressive parts has followed: his first feature, Maggie Gyllenhaal’s critically acclaimed directorial debut, The Lost Daughter, premiered in 2021. The next spring, he was in Cannes promoting two lead roles: in Anna Rose Holmer and Saela Davis’s indie flick God’s Creatures, set in a bleak oyster-fishing town in rural Ireland, and Charlotte Wells’s devastating Aftersun. A beautifully constructed tale of a loving but stricken young father, the latter underscored Mescal as a powerful talent with the ability to both charm and break the hearts of viewers with one downward glance – the film also earned him a nomination for an Academy Award. In 2022 he returned to theatre for the Almeida’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire, going on to win an Olivier last year for his portrayal of Stanley Kowalski.

More recently, two new films have been released: Garth Davis’s Foe, a sci-fi romance in which Mescal performs opposite Saoirse Ronan, and the gut-punching All of Us Strangers. Directed by Andrew Haigh, All of Us Strangers tells the story of Adam (played by Andrew Scott) who, upon falling for Mescal’s Harry, begins to explore a tragedy that has cast a long shadow over his life. A dizzying dance ensues between the imaginary and the corporeal, as Adam flits between dreamlike visits to his dead parents and the very visceral beginnings of a new sexual relationship – viewers leave haunted and moved.

The British filmmaker Haigh is known for his works’ intimate scale and emotional heft. There’s Weekend, which dug at real and tender spots in gay male sex and relationships; 45 Years, starring Tom Courtenay and Charlotte Rampling, who depict a couple on their sapphire wedding anniversary processing an earth-shattering secret; and Lean on Pete, a coming-of-age tale of a motherless runaway boy with Chloë Sevigny and Steve Buscemi. In each quietly vigorous work, Haigh’s incredible casting and spare dialogue enable truly believable characters to wrestle with past trauma, belonging and love.

On set for his latest lead, in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator II, Mescal Zooms from a candelabra-filled room in a sandstone palace in Malta with Haigh, who’s at home in London. Here, the pair discuss the radical tenderness of their new film and what it takes to express inner conflict with the delicate restraint they are both known for. It’s the first time the collaborators have had the chance to talk together in public about the award-winning film.

Paul Mescal: I was just hanging out with the Searchlight crew in LA and they were saying that you were taking two weeks’ respite, having gone to every state in the US for this film.

Andrew Haigh: Yes, but I have to remind myself that sometimes you make a film and nobody is very interested at all. When people do care enough to want to talk about it, then you can’t be too grumpy. It’s why we made the film in the first place, to connect with people.

PM: But it’s that weird transition, isn’t it? I imagine there are many transitions for you – the writing process into the shooting, which feels like a private experience, but then you’re making this for an audience, so once you finish filming it, it’s for public consumption. Which is the most frightening part of it. But yes, when something feels like it registers with an audience, you’ve got to run with it because it doesn’t happen all the time.

AH: It’s definitely frightening releasing the film into the world. I try very hard during the actual making of the film to forget about all the stuff that comes afterwards. It’s almost too much pressure, isn’t it? I’m sure it’s the same for actors.

PM: You almost do forget. You get into a shooting rhythm but then the hardest bit for an actor is once you’ve handed it over. I kept bumping into you in Soho during the editing and I felt like I’d given you a version of my own child and you would be like, “Yes, that was really good.” The number one rule is try to avoid your director while they’re in the edit because they’re never going to give you any information that’s going to satiate you at all.

AH: Sorry about that. [Laughs.] In truth, it’s because I’m always so nervous about what an actor is going to think of the film.

PM: Did you feel nervous with All of Us Strangers? Because from a performance side of things, I feel like it’s really strong across the four of us [including Claire Foy and Jamie Bell, who play Adam’s parents].

AH: I was never worried about the quality of the performances. You are all incredible. It’s just when you’ve made something together, trusted each other and worked so hard on something I don’t want you to be disappointed. It matters to me that you like the film. You get offered lots of roles and I always want an actor to feel like they’ve made the right choice. How did you know you wanted to do this and not do something else?

PM: Because it was the best script. It sounds basic but it goes a long way – it was the best thing I’d read in the longest time. And that’s both a testament to your talent as a screenwriter but it’s also that it just becomes immovable in my brain. Something else can come in and it might be stretching a different muscle, or it might pay more money, or it might be to work with a director I like. But this had all those things. Ultimately it was the story, and the character felt both in my wheelhouse and a perfect stretch at the same time.

AH: When I knew that you were interested in the role of Harry, I was a little bit flabbergasted.

PM: I’ve heard you say this in interviews and I’m so curious as to why because I don’t know any actor worth their salt who wouldn’t be – I’d love to know how many actors you sent it to who didn’t respond to it.

AH: Only a few. And they said no.

PM: They said no?

AH: [Laughs.] I’m not going to name any names.

PM: Did you get a flavour of why they said no?

PM: That’s why I love that part so much – because ultimately it’s a supporting part in terms of the script and what the central story is, but he’s also a supporting human being to Adam. It’s like his whole function is to put the scaffolding up around Adam to protect him.

AH: That’s a beautiful way to put it – putting up the scaffolding to help him rebuild.

PM: And then you give such amazing clues into Harry’s own world – just drip-feeding them in tiny moments. You really see that there’s almost another film to be written about Harry that mirrors Adam’s, but you have the restraint to give enough of that without taking the focus off Adam.

In general you write such actor-friendly scripts, which is why if there were a part that size in another screenwriter or director’s hands, I probably wouldn’t take it. But there was nothing about that part that felt small to me. That character has had the same impact on me as other leading roles I’ve played. That’s about the imaginative space that you allow the actor to create – it allows the audience to project.

AH: And he is so important – he’s fundamental to Adam’s change. Still, in the hands of an actor who can’t embody that character, truly understand it, then none of it works. You have this amazing ability to deepen characters – to allow us to understand that a backstory might exist, even if we don’t know what that backstory is. The minute we see you at Adam’s door I can understand the pain, the longing, the need that Harry has, all lurking between your words and gestures. That’s a rare skill. I’m not entirely sure how you do it, honestly.

PM: Andrew, it’s all there in the script. I didn’t invent anything other than the normal actor work – you gave me all the tools I needed and with such economy. Can I say that that scene is one of my favourite scenes that I’ve ever got to play in my entire life. I remember reading it and thinking that you could spend a week on that scene – there are endless alleys it could go down. And I’m so happy with how it felt – it’s the perfect blend of dangerous and sexy and sad, but it’s unclear which part of the Venn diagram it’s sitting in.

AH: And it’s such an important scene too. The film does not work without that scene landing. Although you could say that about so many of the scenes in the film. Every scene asked us all to go to some emotional places. Every scene had its challenges. Some for personal reasons and others in terms of story. When you’re working as a director, a writer or an actor, you are emotionally exposed sometimes.

I struggled a lot with that – even in the writing – how much do I reveal and how much do I hold back? There’s this Nina Simone song, Who Knows Where the Time Goes – she talks at the beginning about a quote by Faye Dunaway, who said she tried to give the audience what they wanted [in Bonnie and Clyde]. And Nina Simone says, that’s a mistake because “you use up everything you’ve got, trying to give everybody what they want”. And I think it is about trying to find that balance, isn’t it? Of, “OK, I’m prepared to give this, but I don’t want to give this.”

PM: I would forget sometimes that you conjured up these people and it is scary, in the most exciting way, to be in your company and thinking, “I know he’s hiding stuff.” Through the writing process, the shoot, the edit, were you thinking about what your lines in the sand were when it came to talking about the movie? Or is that something that came in the weeks before the press run?

AH: Yes, I tried not to think about it too much while I was doing it because it’s really dangerous when you’re making the film to think too much about how the world is going to take it and what people are going to end up asking, because I think I would close up and become afraid. But one of the things I’ve tried to understand is why do I even want to make films?

PM: Why do you want to make films?

AH: I don’t know. Most of the time it’s so painful – the stress and anxiety. But I think for anybody that works in film, there’s part of you that is probably doing it because you just want to be loved by the world. [Laughs.] And the problem is it’s an appalling industry to work in if that’s what you’re wanting.

PM: Yes, because you’ll get it one second and then you’ll lose it.

AH: I always find that fascinating because sometimes things go well and sometimes they don’t and you often can’t even understand why.

PM: What scenes did you find particularly difficult to film? One that jumps to my mind is the scene in Harry’s …

AH: ... apartment.

PM: Yes, that was one that took us ... We had to climb a couple of steps to get there. I had performance anxiety – I’d seen how beautiful your work with Andrew had been and I was like, “We’re entering the final couple of minutes of the film and if I fuck it up, it’s my fucking fault.” But it’s one of those few moments when Harry does become the focus of the film for a second.

AH: You certainly hid that anxiety well. And you nailed the scene. It’s heartbreaking. I also adore the scene between you and Andrew in the bed halfway through the film. I can’t tell you how beautiful you both are in that scene. I feel like I’ve tried to capture intimacy a lot, but there is something special going on here, the way we see you opening up to each other. It is so delicate and tender, the way you hide and reveal.

PM: But that’s what I love about the writing as well. You’ve seen versions of those scenes in films where you see a character repress or hide what he’s feeling through a smile. But the thing that is different about this scene is that there’s somebody on the other side of the bed who loves him and tells him that it’s not OK to do that. And the thing I find so upsetting about that scene is that Harry says, “I’m marginalised by my family et cetera ... but it’s fine.” And the line that devastates me is when Adam says, “But why is that OK?” It’s such a simple line.

AH: Agreed. It’s about knowing that someone cares enough about you to push a little deeper. There’s an exhalation you do in response to that question, a giggle, a gesture and then you stretch. It’s one of my favourite moments in the film. We’re so close to your face, close enough to see Harry’s mind working, asking himself if he can fall deeper into this relationship. It’s those moments I am obsessed with trying to capture. Do you plan for those moments?

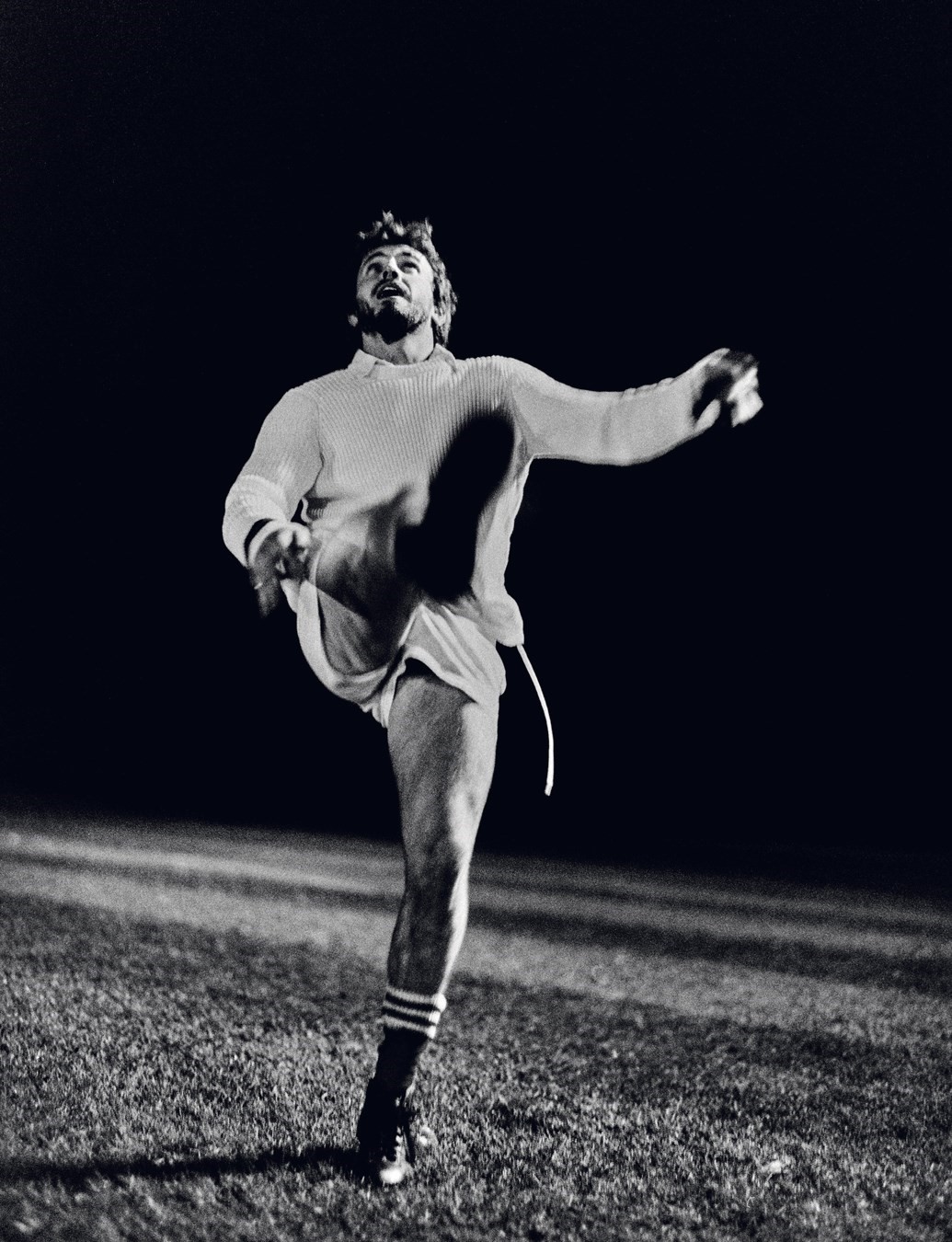

PM: That’s not something I think you can prepare for as an actor. You can’t go home and do your homework and be like, “And when he says this, I’m going to stretch and make a little noise.” You just can’t.

AH: One thing that always surprises me is how you can find and sustain that feeling of intimacy with all the trappings of a film set around you. Men in shorts. Cameras in your face. I’m always amazed when actors can ignore what is going on around them.

PM: It’s because we want to be adored. [Laughs.]

AH: That’s what it is.

“I’ve tried to capture intimacy a lot, but there is something special going on here, the way we see you opening up to each other. It is so delicate and tender, the way you hide and reveal” – Andrew Haigh

PM: I feel like sometimes, though, it’s blind panic. Because I think acting has the capacity to be the most embarrassing thing that any of us ever do. And it can be in an instant. I’ve seen actors that I really admire do bad, embarrassing things. When you’re in a scene where that’s heightened – say, if your body is on show or there’s an emotional weight to a scene – weirdly, if you’re working with good actors, you can just throw a bubble around yourselves and white-knuckle it. Andrew Scott is just outrageously good.

AH: And you are outrageously good together. We see you fall in love on screen. We believe every moment of it. It feels so genuine.

PM: When you feel close with an actor like that, like with Andrew, it allows a real-life intimacy and a trust that I’ve only had a couple of times – obviously with Daisy [Edgar-Jones] in Normal People, and Andrew, and Saoirse in Foe. It has nothing to do with talent. Saoirse and Andrew are actually quite similar. They’ve got this well of emotionality where all you have to do when you’re in scenes with them is sit there and listen to what they’re saying. Normally they’ll find a way to unlock you.

It sounds reductive but you don’t have to do anything when you’re working with brilliant actors like that. I would say the size of the performance in Foe is much more robust than Strangers, which is big but it’s also restrained and subdued. In Foe, me and Saoirse just had to plant our feet and really go from the gut.

AH: That’s the skill of it, isn’t it? Because you have to understand what the film needs.

PM: I’d say that there’s a similar performance style across all of your films – and that’s the one thing I love about my job, that you get to go into different jobs with different actors, like Saoirse and Andrew, and you put on different hats and you figure it out. Would you say there’s a performance style that you’re interested in generally?

AH: I’d say there is a tone to my films to which a performance style is integral. Although I’m not very good at being able to articulate what that style is. I guess actors will have watched my films before they want to work with me, so instinctually understand the timbre of the performance I like. We usually don’t need to talk about it.

PM: We never actually spoke about it.

AH: But I think that’s the joy of when you’ve made a few films. You can have a reference of what you like. That’s why our choices are important. The choices we make define the kind of person we are. That’s why I wanted to work with you so much. The projects you choose are always interesting. And you’ve had a crazy few years. How does that feel?

PM: It’s a hard question ... Because I never expected this to happen. I had ambitions, of course, but I could never have expected that this would be where I was going to land. Being in drama school, I remember teachers telling me the statistic was something like “only 16 to 20 per cent of you will ever work as an actor”. So I remember getting my first job in theatre and thinking, “That’s it. Somebody has decided to pay me to do the thing that I love.” And then fast forward five years – it’s the thing that I love most in the world and I’m getting to do it with directors that I admire greatly.

“Ridley [Scott] shoots at a very different rhythm – he’s quick and it’s kinetic and wonderful. He knows exactly what he wants. It honestly reminds me of sport in a way that is really satisfying” – Paul Mescal

I’m learning, though, that there’s only so long I can continue going at this rate before it starts to take away from my life – but right now is the time to put the foot down and really work hard.

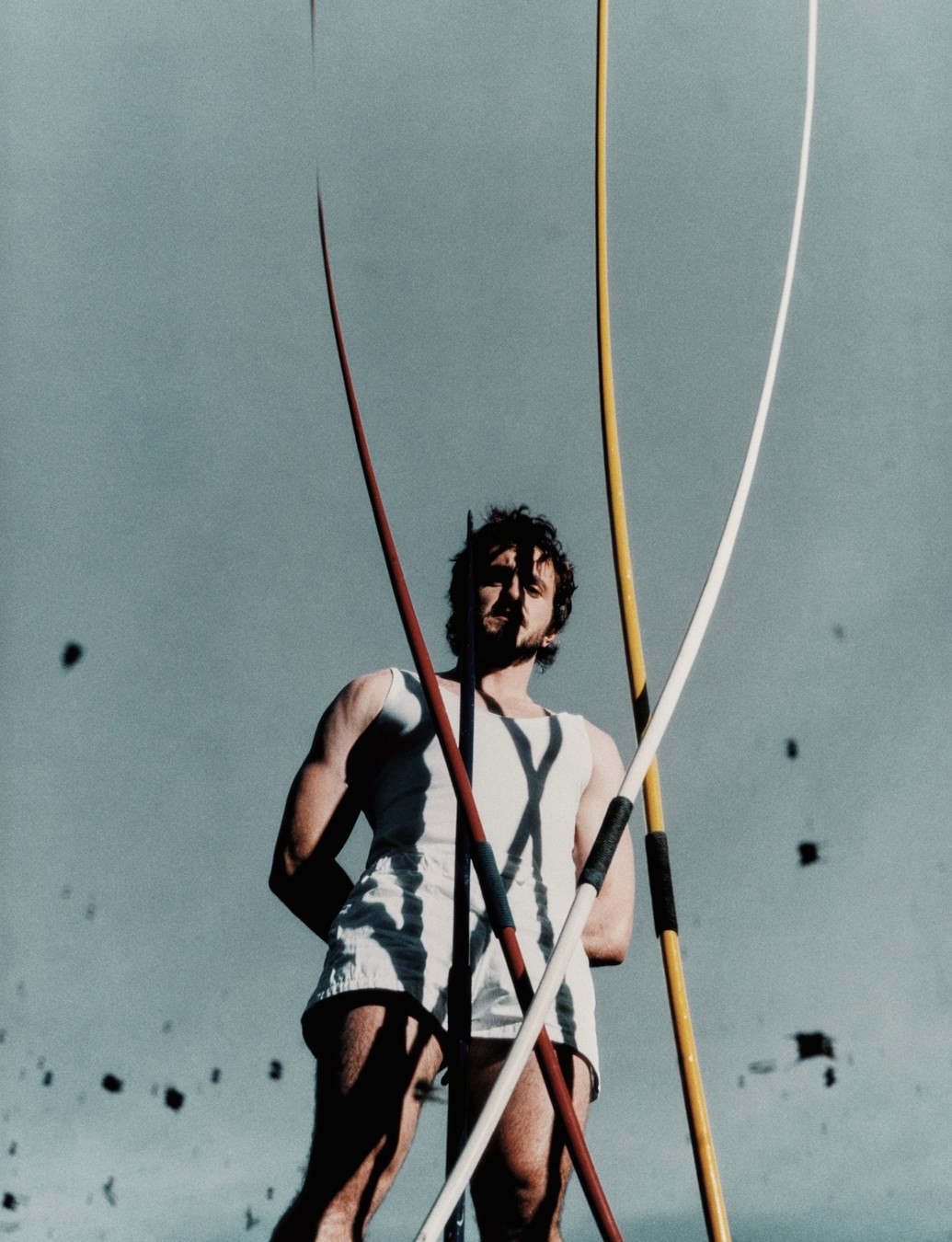

AH: And now you’re doing your first huge movie.

PM: Gladiator comes across your desk and there’s no way you say no to it. But with this scale of film, and to work with Ridley Scott, it’s a no-brainer. Up until this point there have been very few larger films that remotely interested me.

AH: But this is Gladiator. This is not your average blockbuster.

PM: It feels really right. And also there’s the capacity to learn. It’s the first time that I’ve felt a pressure of, “God, I’m worried about box office receipts.” It’s a different metric. But Ridley shoots at a very different rhythm – he’s quick and it’s kinetic and wonderful. He knows exactly what he wants. It honestly reminds me of sport in a way that is really satisfying.

AH: Plus you get to dress up as a gladiator.

PM: We left that point out. That’s the best bit.

AH: You’re going to make a lot of people very happy!

Grooming: Josh Knight at Caren using SAM MCKNIGHT and ARMANI BEAUTY. Set design: Staci Lee Hindley. Lighting director: Max Tomlinson. Lighting assistants: Louise Oates and Jess Hand. Styling assistant: Storm Foster. Tailor: Georgia Smith. Set- design assistants: Tom Hope and Freya Wentworth-Stanley. Printing: Labyrinth Photographic. Production: Eightyseven Productions. Executive producer: Lolly Bedford-Stockwell. Production co- ordinator: Chloe Johnson. Production assistant: Szofia Antonova

All of Us Strangers is out in UK cinemas now.

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally on 29 February 2024. Pre-order here.