How have people’s lives been shaped by the print matter they collect? In a new column for AnOthermag.com titled Paper View, Norwegian publisher, curator and critic Elise By Olsen sifts through the libraries of various cultural figures, learning more about their lives and careers in the process.

It’s the snowiest day in recent memory and I’m on the way to meet Norwegian model and architect Iselin Steiro at her home in north Oslo, which she shares with her husband of 15 years, actor and GP Anders Danielsen Lie. Driving in my tiny car (and mobile library), I plow through the snowstorm that has shut all airports, buses, trams and metros for the day. Anything for a little paper! I make my way through an avenue of tall trees and bushes covered in a thick layer of snow, pulling up to a charming driveway, shovelling my way up to a tar-painted timber house. Steiro and I have been trying to organise this home visit – to review her personal library – for quite a while, yet our colliding calendars have delayed it until today: a weather warning Wednesday of the new year.

The inside walls of the 1915 house, built by her husband’s great grandfather, are vertically dressed in “villmarkspanel” – lengths of cut timber, fileted, if you will, archetypically Norwegian, preserved as is. Each panel is quirky, with the shape following the log’s natural taper, some covered in children’s drawings. As I’m served warm coffee by the heat of the fireplace, I take in the salon of the house, which has a wide window with a gorgeous view of the couple’s garden that overlooks the hills of Oslo. Over to the salon’s left nook, there is a perfectly placed bookshelf, an architectural object – grandma’s original. The white wooden structure abounds with the couple’s collection of books; novels, cookbooks, self-help, books on architecture, fashion, film and photography, her husband’s score sheets. The fashion editor Grace Coddington’s bright-orange memoir next to Dostoevsky (a recurring favourite of the people featured in this column) and a book about Hitler and Nordnorsk Sangbok (Northern Norwegian lullabies). “At some point, all of these were alphabetised,” Steiro says. “It’s all mixed again now. There’s a general resistance against throwing things in this house, but the bookshelf has to downscale as we’re about to renovate the ground floor, which was previously untouched.”

Steiro was born in the little town of Harstad in the northern part of Norway in 1985, surrounded by the solitude of mountains and scenic fjords. The two of us always bond over our connection to the north (our fathers went to school together). As a model, she was discovered on a trip to London with her parents in 2000, stopped on Oxford Street by a model scout while doing some Christmas shopping. Her parents first rejected the idea, until the following day when another scout asked for her name and a Polaroid at Topshop. “I never thought anything would happen from it,” Steiro confesses, “but the scout had given word to a Norwegian model agency, so when I came back I was tracked down by an agent who then wanted to sign me. I never understood how this happened exactly, how they traced me. Could they have looked for me in the civil registry? I mean, children can’t have been in the Yellow Pages then, could they?”

A prima modelling career is truly a paper trail. Steiro has lifted boxes down from the attic with all kinds of archival printed matter for us to go through, and we start by opening the earliest of her books: a model’s portfolio, which at the time of Steiro’s emergence, were physical. They were diligently assembled, often revised and updated, with glossy finishes, laminated plastic inserts, perfect bound, even velour covers. “I carried these under my arm to castings around towns. I would receive faxes with instructions from my agency, ‘Remember to greet this person and that person, and this person is important because so and so.’ They would give me foldable maps to navigate cities I’d never been to before, sometimes with little notes and messages written on them with red markers.” The plastic folders crackle as she flips through them, stuck together by the moist climate in the attic. “This was my first ever shoot,” Steiro tells me, pointing at a colour-washed photo of herself at 14 years old in pale, natural lighting, shot by Norwegian photographer Camilla Isene on one of Oslo’s nudist beaches. “Look at my face … I look like a baby ... I was a baby!” Steiro also unearths early published editorials, original Polaroids, comp cards (a model’s business card, a “best of”) and her first campaign series for a Japanese brand that travelled to her homeland in the north to shoot her (she had just turned 15). “I really wish I had kept diaries or scrapbooks from these times,” she says.

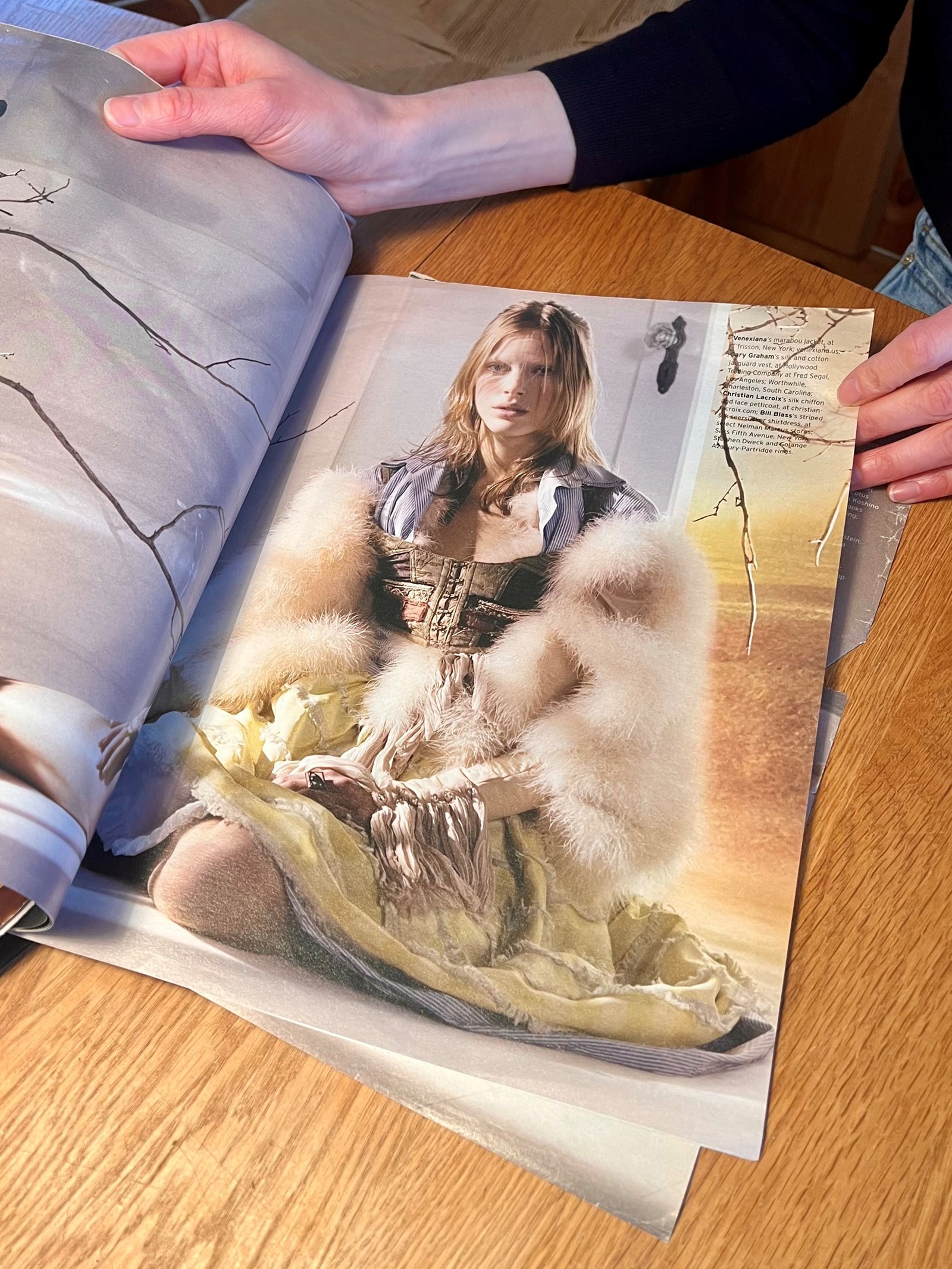

Printouts and tearsheets – pages torn from fashion magazines – that she’s been featured in have been kept in plastic folders. There’s a young Steiro captured by fashion’s most in-illustrious photographers: Collier Schorr, Corinne Day, David Sims, Karim Sadli, Karl Lagerfeld and Mario Sorrenti to name a few, with Steiro donning sharp silhouettes and bleached eyebrows on one of many Vogue covers, as a chic Tommy Hilfiger housewife in an advertising spread, on Prada and Calvin Klein catwalks during her first season (hardly a ‘new face’), in underwear as a Victoria’s Secret femme fatale, or gracing David Bowie’s last ever music video with her presence: Steiro as the surreal, androgynous clone of the man himself. I admire Steiro’s incredibly versatile, captivating and impressive oeuvre as an internationally practising model with heaps of integrity. I also imagine, with a lump in my throat, from one collector to another, what’s left of the magazines after these very dedicated tear-outs. Are they thrown, are they kept? “They’re upstairs!” she says.

Up the stairs, a dozen humble transparent Ikea “samla” (means “collecting” in Swedish) boxes with lids – each box numbered by year on the Ikea barcode – are filled with fanmail, a Steven Meisel puzzle, old call sheets, as well as big format magazines and luscious glossy spreads. 20 years in fashion via V Magazine, Acne Paper, Numéro, W, Self Service and The Last Magazine, all with Steiro on the cover. “My motivation has always been to make a fantastic and extraordinary image. Yet I think that the screens, where images are most often displayed today, limit the artistic ambition of image-makers,” she says. “One can’t really see what happens in a photo on a small device, with the details and the intricacies. And then there’s the acceleration and amount of images: it almost feels like there’s no point in putting all this time and effort into one image because it’s gone in the blink of an eye. All forms of art and culture are in flux, and even if there’s a certain romanticisation, and nostalgia, for the past, I think new expressions also open up for new possibilities. Just look at the fashion shows, they’ve really come into their own right, with film, streaming and a live audience present.”

“I’m 38, I’m not a celebrity, I don’t have many followers on Instagram,” Steiro continues. “I’m happy that my modelling still rolls, even if it’s become a side gig alongside my practice as an architect. I’m intrigued by the parallels between the worlds of fashion, art and architectural heritage, a holy trinity. In many ways I see architecture as a fashion collection or a fashion image; you need elements that create dynamics, balance, particular colour combinations, contrasts, the relationship between the body and space. I like to think of the house as composition.” And what about the architecture of printed matter? “There was a lot more drawing and sketching on paper and by hand at my architecture school than there is now that I work for clients as part of an office. Perhaps architectural drawings were previously valued more than they are now. Fashion photography became the form of expression when the idea of fashion illustrations expired. The same goes for architecture; rendering is now a genre in itself, or we build models and photograph them.”

Steiro starts walking me out. “My archive becomes thinner and thinner by the years. At some point I started downloading and collecting images on my computer as these little files in unstructured folders,” she says. “One thing I highly regret is not downloading every single image of myself on Style.com. Us models were always photographed backstage in various situations, sitting around, chatting, giggling and drinking Coke. Imagine that for my scrapbook! These photos are now historical material just because the arena, that of the fashion show backstage, is highly professionalised today. Capturing the fashion spectacle and fanfare, mystique … It’s a lost moment in time! God knows where this material is.” All in all, the models remain, but the apparatus evolves and changes. I exit Steiro’s house through the basement, with flooring of terrazzo created by rocks that she has collected through the years – “I guess I’m more of a utilitarian collector” – and I am greeted by the cold. As Iselin Steiro turns to architecture, this printed matter reminds her of a career that’s outlived more than two decades of fashion editors, creative directors and photographers that come and go, regardless of who is behind the fashion joystick. Hers is an archive as aide-mémoire.