Dennis Cooper has been pissing people off for decades. In 1983, two well-known American poets awarded him an ‘Aids Award for Poetic Idiocy’, alongside a photograph of a beaker filled with infected blood. And it wasn’t wasn’t just homophobes he had to worry about: following the publication of his second novel, Frisk, an anonymous activist took exception to Cooper “murdering” fictional young men and distributed fliers calling for his death, in what was neither the first nor the last time that the violent quality of his work would provoke controversy in the queer community. But today, now that the dust has settled, Cooper’s legacy is assured: he is widely recognised as a titan of queer literature, and as a formative influence on a new generation of writers, musicians and filmmakers.

Before moving to Paris, where has lived for the past 15 years, Cooper spent most of his life in Los Angeles. In the 1970s, he became involved in the underground literary world, organising readings and eventually launching his own independent press. He published a number of poetry collections in the 1970s and early 1980s, along with a novella, before publishing his first full-length novel, Closer, in 1987.

This would become the first part of a cycle of novels inspired by George Miles, a friend that Cooper met in high school, who he fell out of touch with and would later discover had died by suicide. The fictional George is the enigmatic heart of Closer, a novel about a group of gay teenagers in the American suburbs, among them an artist, an amateur pornographer, a nightclub promoter launching a party in his parent’s garage, and a deluded fantasist who thinks he’s a famous singer. Fragile and passive, George “twitches and trembles like a badly tuned hologram”; he is envied, desired, pursued, discarded, exploited, abused, and at one point narrowly escapes a brutal death at the hands of a serial killer (other characters aren’t quite so lucky). For all the novel’s violence, Closer is as much about the indestructible human need for connection – even its murderers are driven by a desire to peel back the skin and truly know another person.

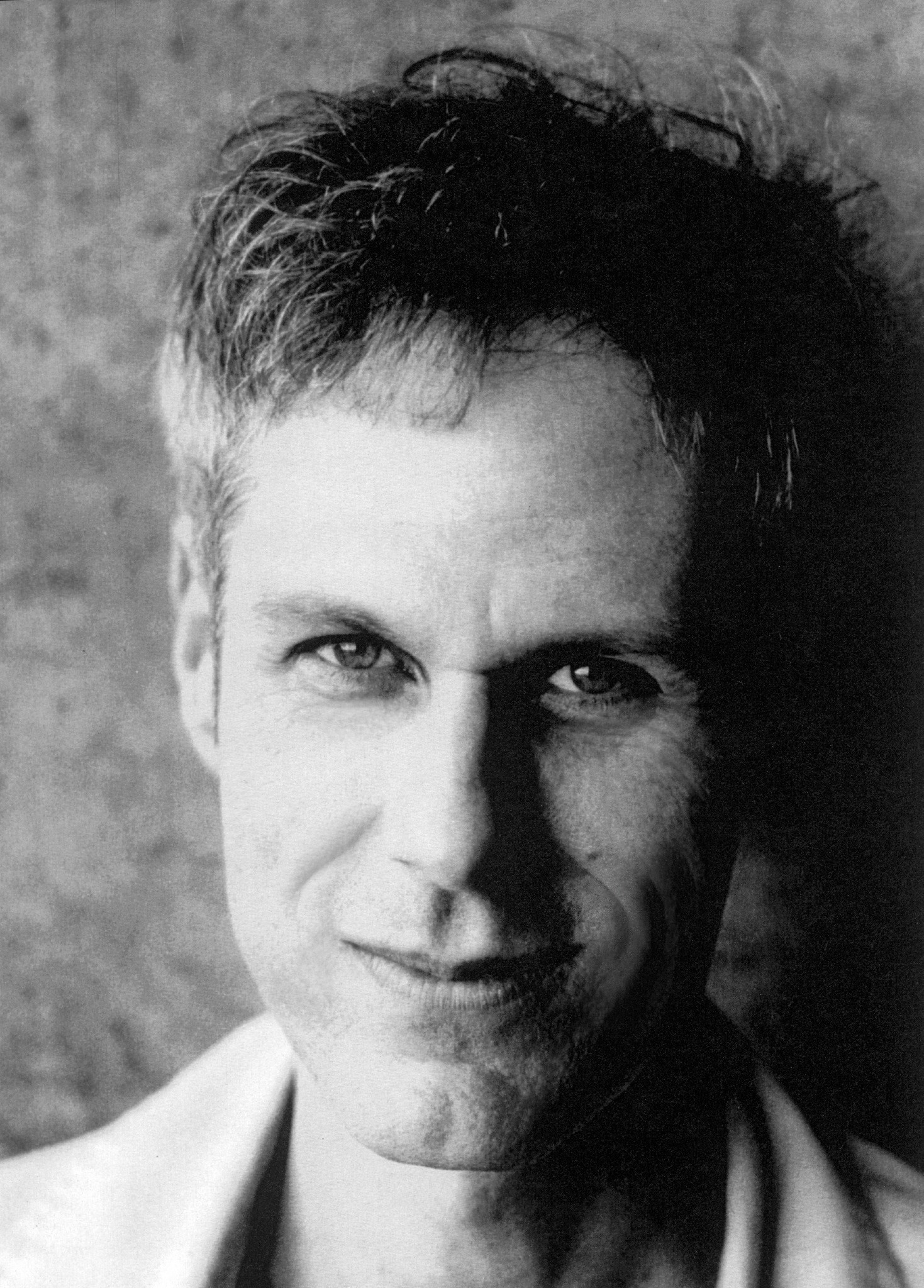

To mark Closer being reissued by Serpent’s Tail this month, I spoke with Cooper over Zoom. In contrast to his reputation as a writer of dark, shocking material, I found him to be extremely affable and warm, as well as being one of the most relentlessly curious and enthusiastic people I’ve ever spoken to: he seems to find everything really, really interesting. We spoke about Closer, sex, violence, censorship, and how queer culture has changed over the years.

James Greig: I’ve read interviews where you’ve rejected the idea that your work – or that literature in general – should have a didactic message. But throughout your career, the theme of young men being chewed up and spat out by adults occurs again and again. Do you think there is a moral viewpoint in there?

Dennis Cooper: I mean, I’m a moral person, so I think there must be. But my interest is in triggering thought and examination in the reader. I’m not interested in laying out something that you’re supposed to agree with or be persuaded by. I’m interested in letting the reader figure it out for themselves. It’s up to them if they want to close the book and go “fuck this” or if they want to go along with it and find out where their sympathies lie. The moral of the books is actually there, it’s just not presented in a conventional way.

JG: It seems like the characters in Closer are searching for a sense of intimacy and connection which always eludes them, almost in an existential way. What do you think about the possibilities for connection between two people?

DC: Well, I strive for it and I believe in it. I think it’s more difficult and complicated when sex is involved – there’s a certain kind of deranging pleasure that mixes everything up. Obviously, it’s possible – millions of people have very intimate, close relationships with people they have sex with – but I guess I’m still more interested in comrades than in romantic affiliation.

JG: So do you think platonic friendship is a more reliable way of achieving connection with other people than sex?

DC: I don’t think it’s a hierarchical thing. They’re just very different from one another. There’s a kind of sanity in friendship and the power balance is very clear. I’m an anarchist, so I’m always thinking about power structures. And I think friendship is a much more balanced thing.

JG: Do you think being an anarchist plays into the way you write about power dynamics in your novels, particularly when it comes to sadomasochism?

DC: Sure, it informs everything I guess. I don’t have an ‘A’ with a circle around it on my forehead or anything, it’s just how I’ve always been since I was quite young. In some of the situations in Closer, there is an extreme power imbalance and objectification. I’m very interested in sexual objectification, but I also find it very dangerous, and of course power is a big part of that. Beauty gives you power, but it also makes you very vulnerable. So for people who are young and attractive, it’s complicated.

“There’s a kind of sanity in friendship and the power balance is very clear. I’m an anarchist, so I’m always thinking about power structures. And I think friendship is a much more balanced thing” – Dennis Cooper

JG: One thing I found fascinating about the character of David is that even in his own fantasy of being a pop star, he is miserable. He could have imagined himself as someone with talent and critical acclaim, but instead he is so contemptuous of his own – entirely fictitious – career, music and fanbase. Why do you think that is?

DC: Well, I used to be really interested in teen idols. At the time I was reading those magazines that they were lionised in, and I had a good friend who was a pretty big teen idol, who would tell me what it did to his head and what his relationship to the fans was like. I found it interesting because it’s such an extreme form of objectification. The fans are a million miles away from them. There’s no intimacy there at all. When they would be interviewed in teen magazines they would all say the same thing: say like, “I want a really nice girl, I don’t care what she looks like!” It was all surface, and then the fans would imagine that when the boys were singing those songs, that’s somehow what they really felt.

JG: It occurred to me that if Closer was written today, David wouldn’t even need to have this fantasy about being a celebrity – he could just go on TikTok, get 5,000 followers and achieve a facsimile of that experience. In general, how do you think the experience of adolescence has changed between the time you wrote Closer and today?

DC: Technology and the internet have changed everything, but I don’t think what people want is very different at all. Apps like TikTok make fame accessible: you can become famous just by being cute and doing something silly, which obviously was not the case before. The celebrity thing is out of control now. There was always celebrity, there were always people like Jayne Mansfield who were famous for being famous. But that’s so extreme now, with the Kardashians and all these ridiculous people. I was just reading five minutes ago about this football player who’s dating Taylor Swift or something – there’s endless amounts of interest in this stuff.

JG: Reading Closer, I was thinking that some people would react really badly to this if it came out today because queer culture is so censorious now. But then I did a bit of research and found that you did actually get quite a lot of backlash from other queer people at the time. Do you think queer culture today actually has become more censorious?

DC: It’s not particular to queer culture – everybody’s more censorious now. Well, not everybody, but it’s a very prevalent thing regardless of your identity. I did get a lot of shit back when those first books came out. At that time though, it was the Aids crisis, and people were really angry that the work was not political enough, that it wasn’t agitprop – that was the main beef. Although, I did get a death threat because I was killing boys in my book, which meant that I should be killed. So I don’t know [if the culture is more censorious]. My friends are not like that at all so I don’t have any experience with it. I’m sure there are people out there that still think my work is disgusting and horrible and should be stopped, but I don’t really know. The good thing is that nobody gives a shit about books anymore!

JG: In the 90s, you described gay literature as a “modest, inbred little genre” that was “intellectually soft and barely artistic, except in the most bourgeois way.” Do you still feel that way?

DC: Oh, I think it’s the best it’s ever been. Back then it was very segmented: there were gay male writers and lesbian writers. But I was very involved in queer punk, and that was very exciting because it was absolutely not about that: it was absolute equality, it was women and men, any gender, any race. So that’s always been my preference, and now you really see [that segmentation] being broken down. I read experimental work mostly, and there’s tonnes of work of all kinds being published, really transgressive stuff, really brainy stuff, stuff that’s very meticulous and almost conventional, but very, very good. Also back then, the major presses dominated everything and you had to publish with them. Now in the US, there’s a million little independent small presses. So I think it’s a fantastic time.

“I’m very interested in sexual objectification, but I also find it very dangerous, and of course power is a big part of that. Beauty gives you power, but it also makes you very vulnerable. So for people who are young and attractive, it’s complicated” – Dennis Cooper

JG: Right now, in the UK, the US and many other countires around the world, we are seeing a resurgence of anti-gay, anti-trans politics. How do you think the present moment compares to the 80s and 90s?

DC: It’s different now in the sense that it seems to be encouraged and cool to be anti-gay; it’s acceptable, thanks to Trump and all those fuckers. They’ve made it something you can publicly announce, whereas before, there seemed to be a lot less people who were really extreme.

JG: Even compared to the 80s?

DC: Yeah, people would be homophobic, but there’d be a level of embarrassment on their part, because it wasn’t cool to be homophobic or transphobic, or racist or any of those things. And now there’s this huge contingent of people in the United States where that’s completely acceptable. You would have thought that by now we would be way beyond that stuff, so it’s shocking to see it come back so vehemently.

JG: What do you think of the argument – which could probably be applied to something like Closer – that at a time when gay people are being smeared as degenerates, perverts and predators, it’s irresponsible to play into those narratives?

DC: Again: books are not important. What I love about books is that the reader has all the power. If you don’t want to read it, you close it, or you don’t buy it. It’s not in your face, it doesn’t chase you down the street, it’s not playing in the supermarket. I’ve been writing difficult books for a very, very long time and as far as I know they’ve never led to any acts of violence. So I think it’s a bogus argument, just like [the] ’video games cause school shootings’ [argument]. I think people are smarter than that, and not so easily influenced.

JG: Do you have any advice for young people who want to be artists?

DC: Oh, that’s such a hard question. You have to have tremendous self-belief, and you have to be kind of a maniac in terms of your energies, and you have to be really disciplined at the same time. It’s a hard trio of things to match up with. I’ve always written really weird stuff that’s been completely off to the mainstream. I believed in it and worked extremely hard, and it’s gone very well for me. Having a life as an artist is the best, you get to stay a young person for your whole life and continue to make stuff, it’s very exciting. So if you want to make art of some kind, just throw yourself into it, make it the centre of your life and then pay the bills however you can.

The new edition of Closer by Dennis Cooper is published by Serpent’s Tail, and is out now.