How have people’s lives been shaped by the print matter they collect? In a new column for AnOthermag.com titled Paper View, Norwegian publisher, curator and critic Elise By Olsen sifts through the libraries of various cultural figures, learning more about their lives and careers in the process.

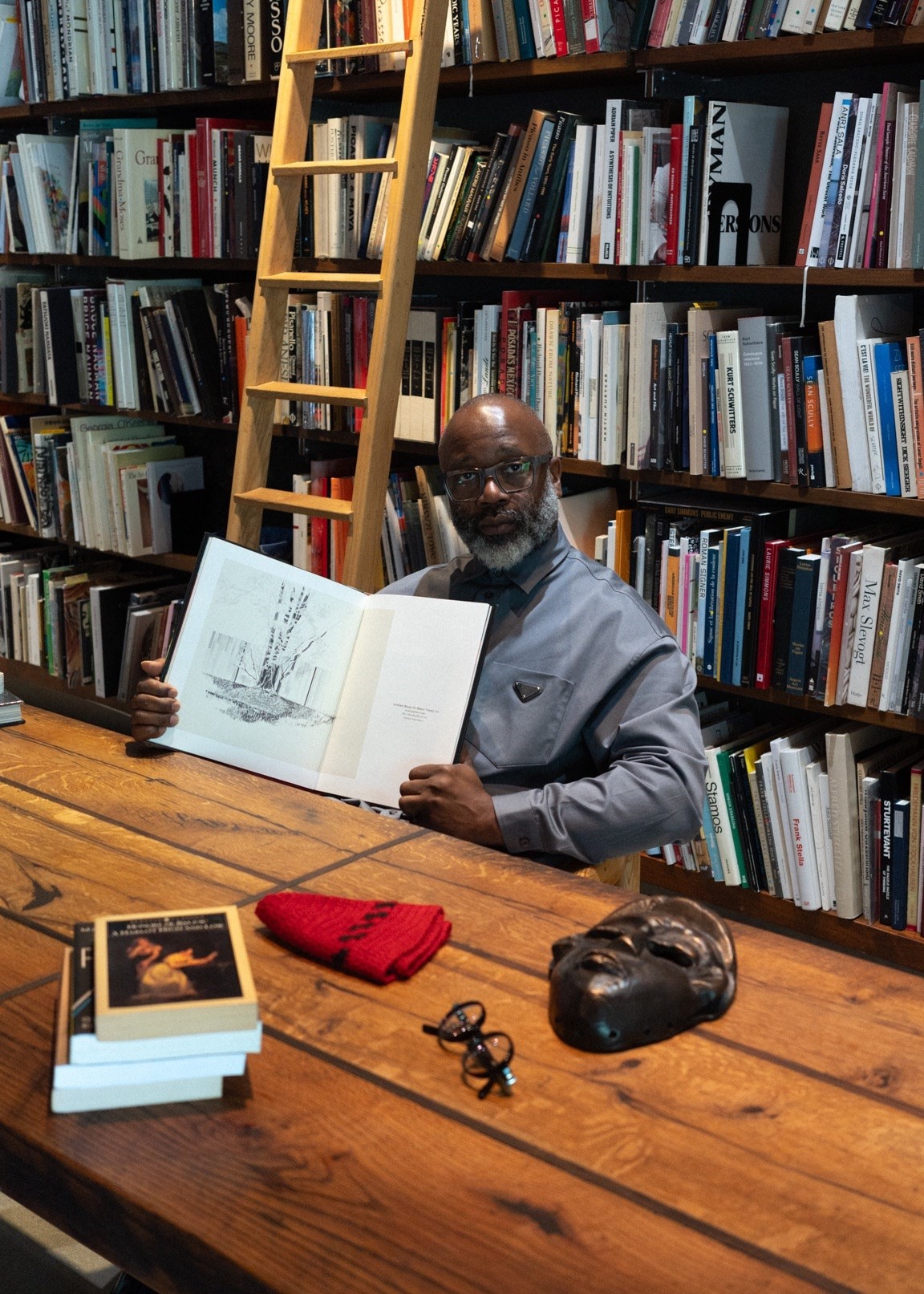

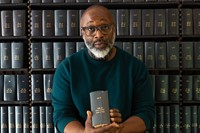

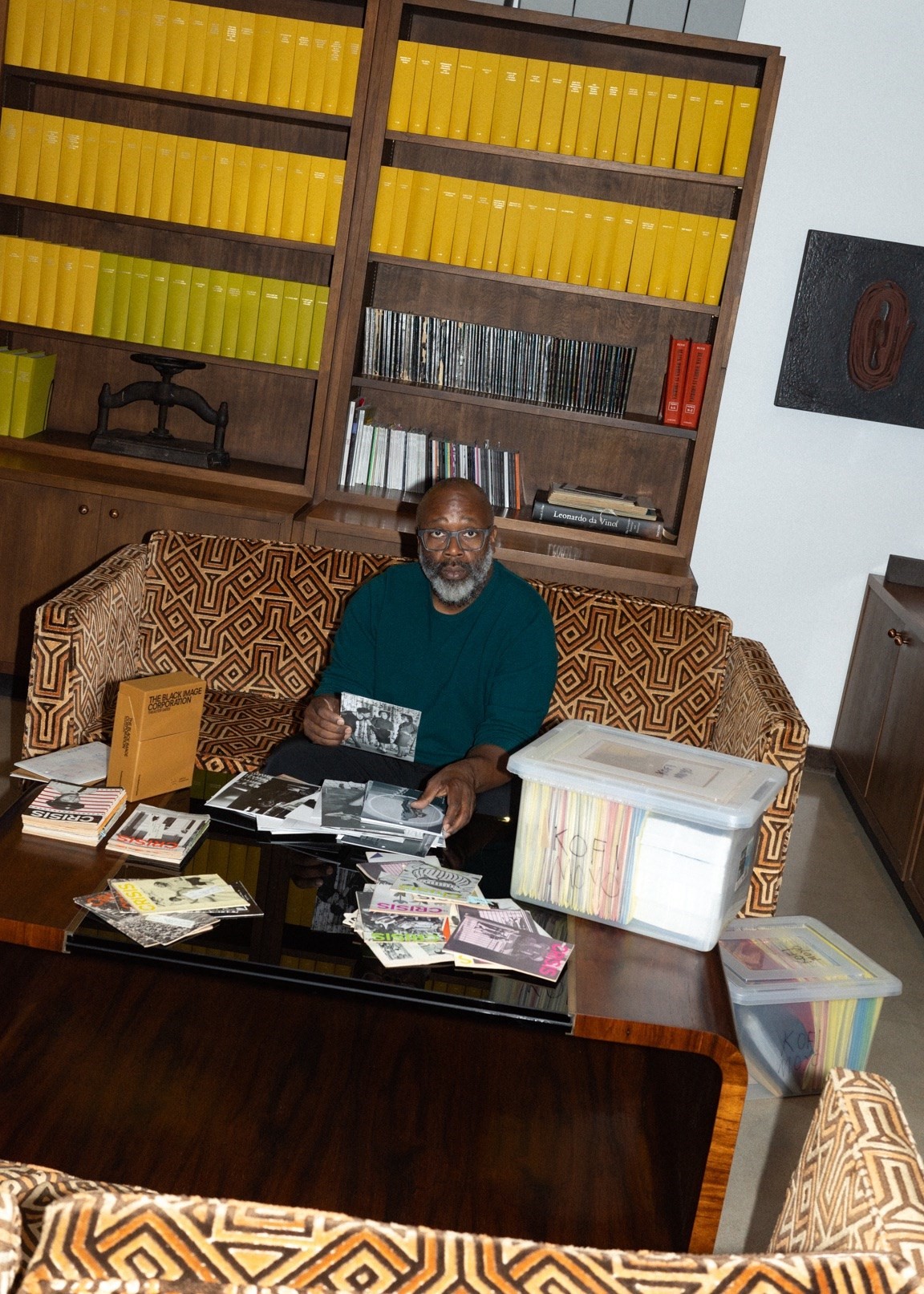

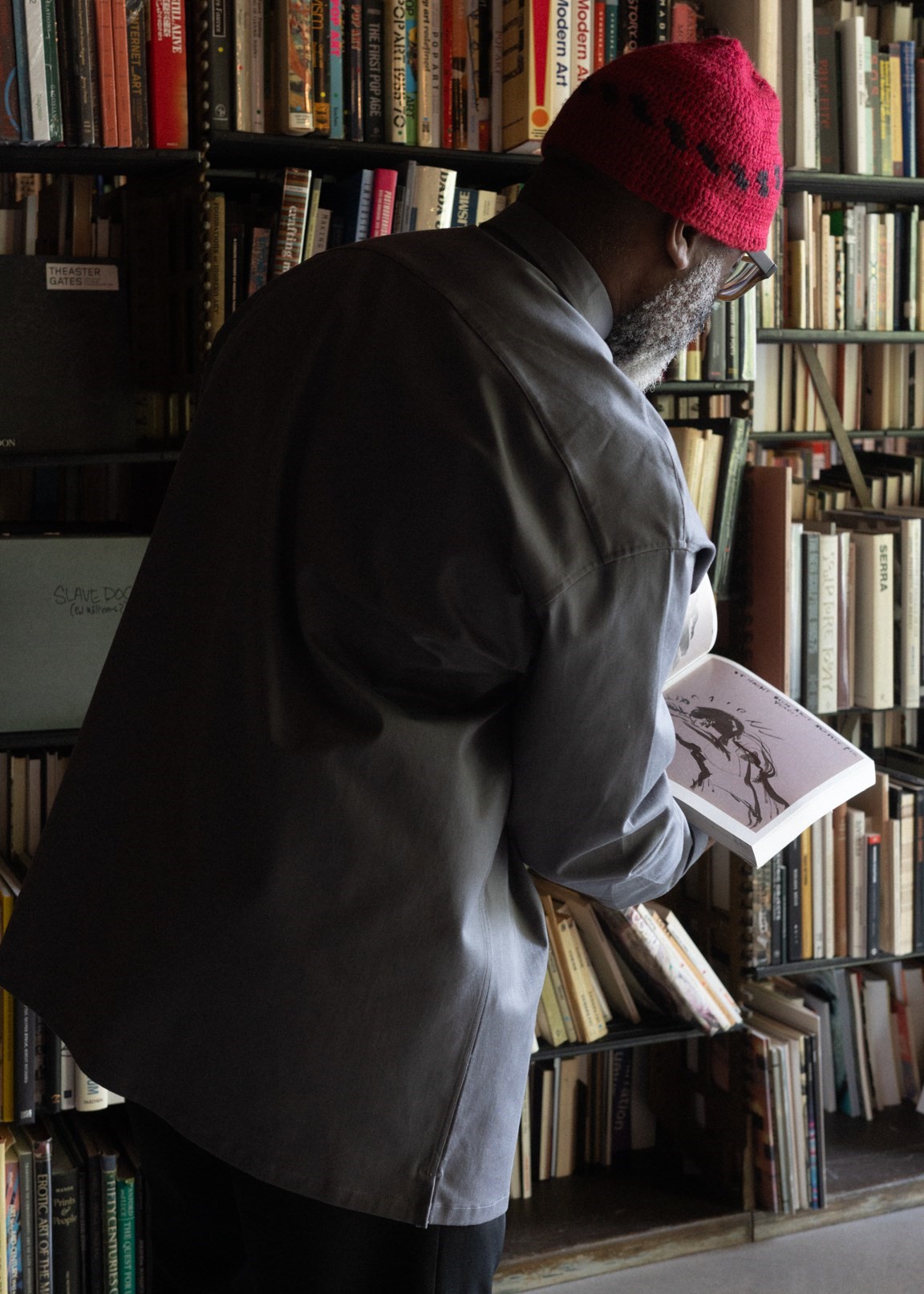

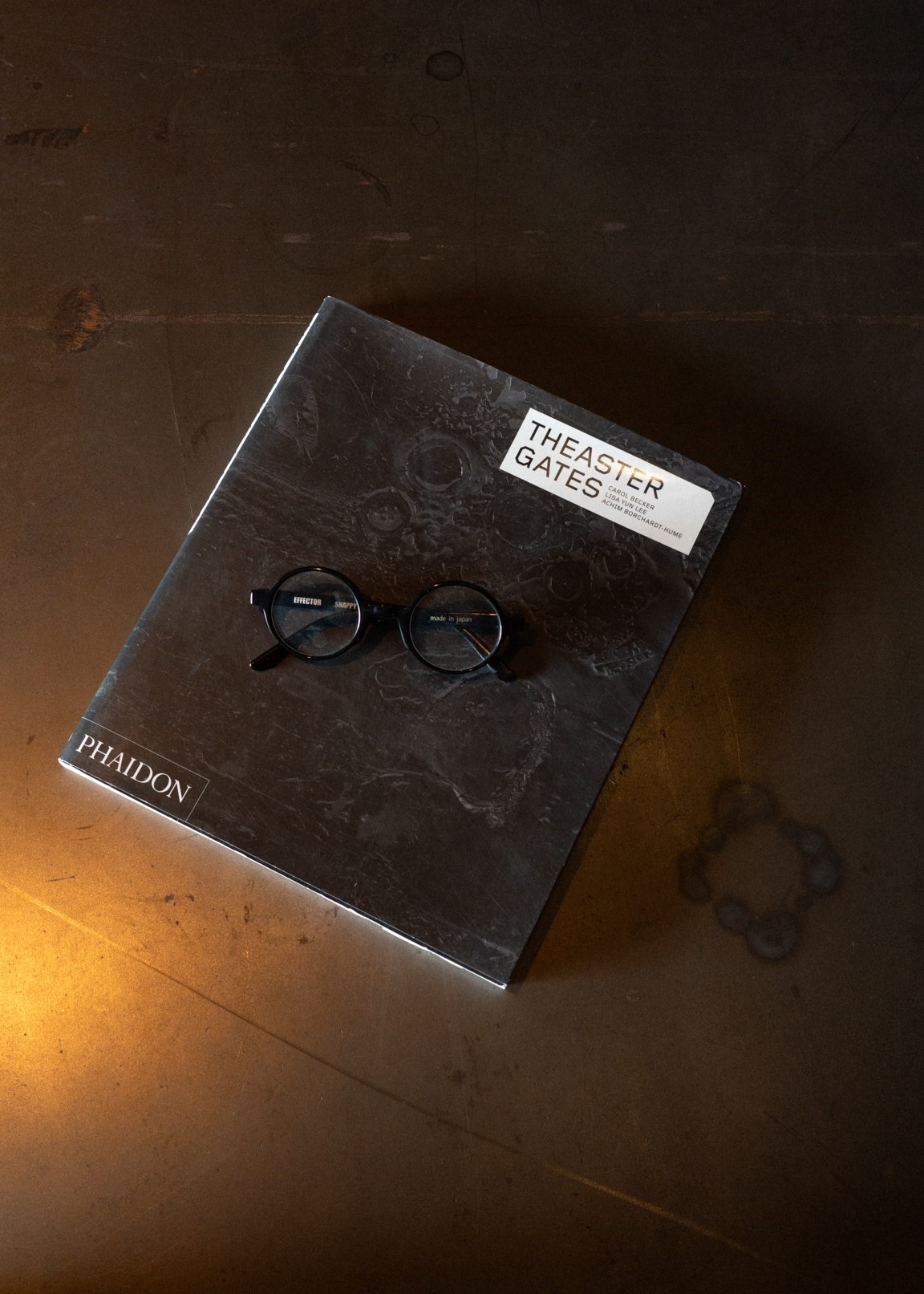

Theaster Gates – the renowned American artist and professor – is speaking from his studio in Chicago, surrounded by his pertinently organised personal archives. I am in the Norwegian woods. Gates has been a long time coming for this column, as he is both a mega private collector and an impressive institutional collector. His space is a reservoir of books and periodicals, but also vinyls and pottery. Each archive is organised, managed and kept separately, whether it be in his Chicago home, in South Side’s Stony Island Arts Bank (a hybrid gallery, media archive, library and community centre that he founded in 2010), or in this art studio. In a way, his collections are placemaking tools. All the branches of archives and libraries are all owned by Theaster, yet some objects made more sense to him than others to be shared institutionally: “they were too big for my personal consumption alone,” he says. Gates’ collection can be seen as a matryoshka doll: within one overall collection, there are many more micro collections.

Collecting has been in Gates’ DNA since early on. In high school, he would go to thrift stores and buy used men’s ties and not only wear them, but roll them up and arrange them by colour and pattern in his drawers. “I have a preoccupation with organising chaotic things,” he explains. His first big collection was his glass lantern slide collection from the University of Chicago: 60,000 images that had been used to teach art history for almost a decade. Gates collects out of love, but also as study aid. “I felt like these glass lantern slides could help me to learn art and architectural history, and further my knowledge and my craft,” he says. “I was imagining that they would keep me busy and give me purpose.” Out of this, his collection started to grow, mostly through personal relations – “it’s not like I’m going around scavenging for things!” – inheriting collections from the likes of the late super athlete Jesse Owens (a collection of “mostly swinging jazz from the 1920s and 30s”), the legendary Chicago record store Dr Wax (a collection of “early, kind of gangster stuff”) and the potter and early queer feminist Marva Lee Pitchford-Jolly (a collection of “albums by female soul singers which was given to me by her partner Earnestine when she passed away”) – all three in which he keeps at home. They all have an end date, whether it’s when the person passed, or when the business went out of business.

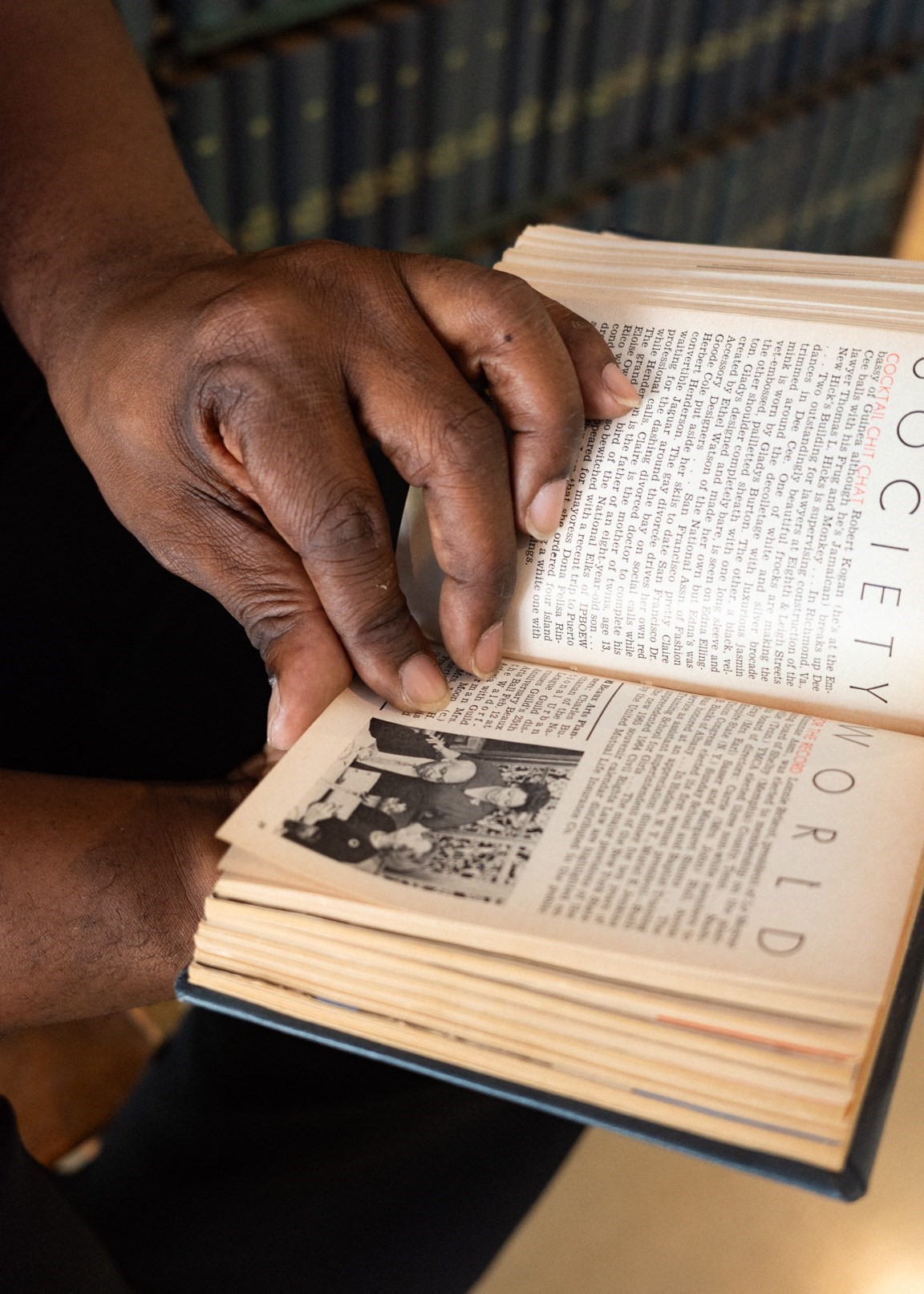

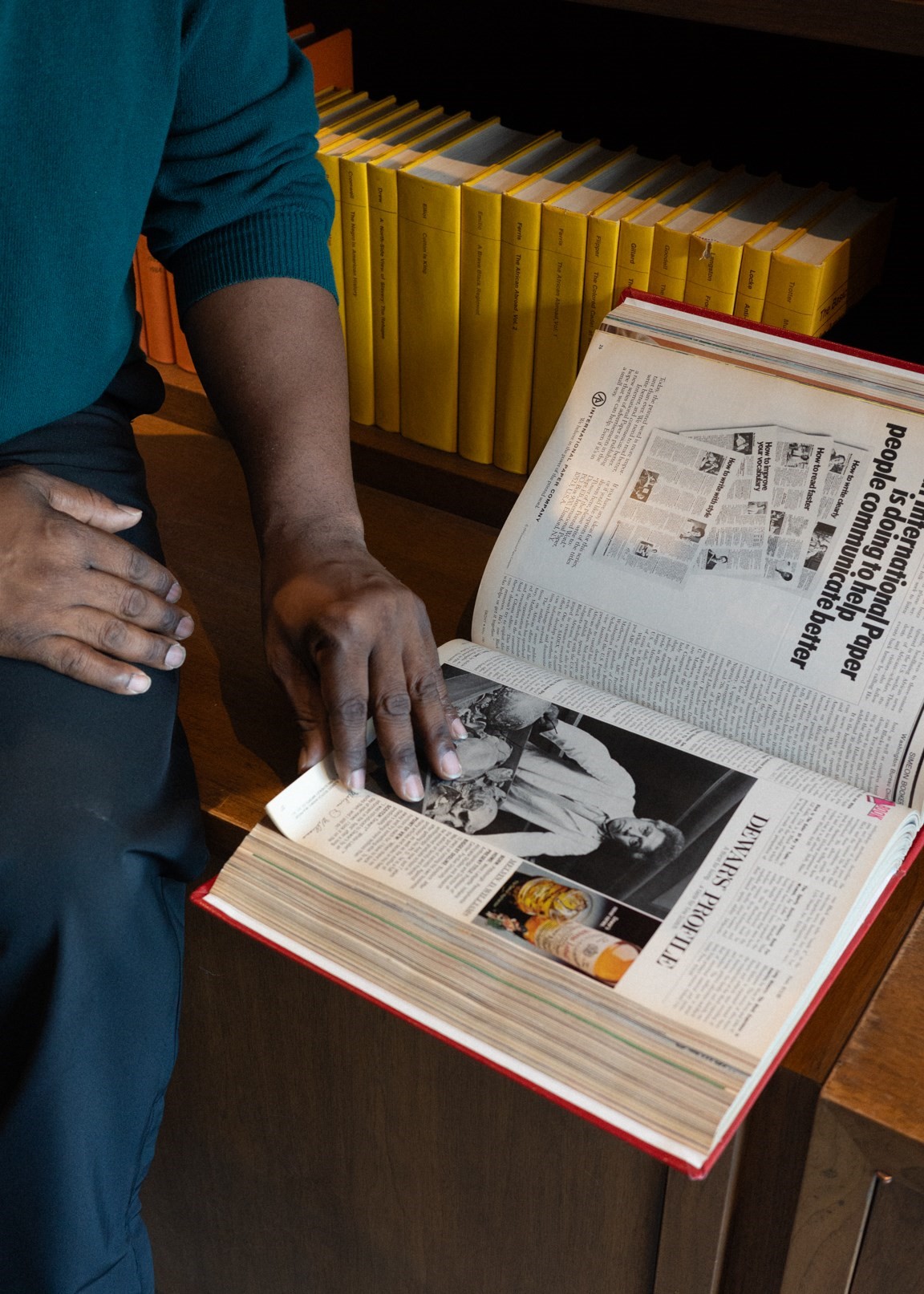

Through his friendship with Linda Johnson Rice, the inheritor of the Chicago Publishing company Johnson Publishing, he personally received the complete collections of two very important periodicals: Ebony and Jet magazine. “These titles published the who’s who of Black America,” he says. “I think it’s the most complete Black-Amercian library that I could ask to have, that’s owned by a single group.” These collections were then donated to the Rebuild Foundation, another of his projects which is housed inside Stony Island Arts Bank. “Linda is extremely proud of her mum and dad for having built Johnson Publishing. She had given me permission to take their books and personal belongings, and to do something with it that would remember the entrepreneurial and intellectual contributions that her parents had made. On one level, these objects carry the power of one of the most important Black legacies in the United States. I had the privilege to try to think whether to exhibit them as historic objects or to use them to continue the tradition of Black entrepreneurship in Southside Chicago.”

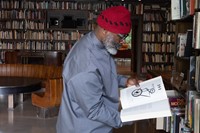

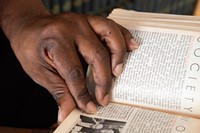

There’s an immense generosity in opening up an archive freely for people to use, yet collections are nothing without the bodies they touch; it’s possible to enter, to go inside and use the collections at the Rebuild Foundation. We discuss the possibilities of ‘usage’ as a way of protecting or conserving. “For me, there are a few ways to amplify memory. One way is to put it in a box and protect it,” says Gates. “Another way is to continue to use it and acknowledge that the reason that I know what I know is because I’m reading a book that is not in a vitrine. In fact, it’s on my desk and it’s open. It continues to age and wither and crack and I get to be the keeper of that knowledge alongside all the other people who read that book. I wrestle with which mode is the most appropriate for various things, and I think that’s part of the excitement of having a living artist work with old things.” Collecting, it would seem, is not a neutral act.

Collecting is also real estate, and the question of ownership keeps lurking in this column. Gates' Rebuild Foundation is increasingly growing, and more entities beyond the Stony Island Arts Bank are being added. For those who collect, there’s a need yet fear for space – a fear for being kicked out of your storage space, your studio space, your apartment, and having to carry all these objects out and with you. Our collections demand space. “We’re fortunate and in pretty good shape because a year from now, the Rebuild Foundation is moving from the Stony Island Arts Bank, which is owned by me, to the St Laurence arts incubator, a building which Rebuild was able to acquire and raise money to renovate,” he says. “We will migrate a series of our collections over to this building so that they can be used by artists and scholars more regularly. I think we have more of an emotional spatial concern, as in: ‘what will this building mean when the archives are gone?’ and ‘will this other building be an adequate space to hold our things?’ We’ve been very fortunate to own our space and protect ourselves from the idea that somebody else looming might kick us out. I would say to you, and to others who are collecting things: allow space to be an important consideration, whether you’re renting or trying to buy something. Talk to people about sympathy and empathy toward the collection being in a particular place. The longer it stays in a place, the more it marinates. If you’re upending it constantly, it could feel hectic and frenetic in a way that might not be so good.”

“Let’s create a deep physical and intellectual encounter with this Black archive. Let’s confront them with the truth of Black radical intelligence and Black imagination” – Theaster Gates

Sometimes, the conditions that govern where our objects are are simply the conditions that we live in. “The truth is, people live with their things, in the conditions that they live with them. So if they’re in the tropics, and they have a very rare first edition of Dostoevsky, it might be a bit humid, the pages might be a little bit wilted and withered when it ends up at a thrift store or an auction … That’s just the truth of the life of a book, or a magazine!” In many ways, the perfect archival situation feels like a utopia. I collect artist’s books, periodicals and other printed ephemera dating back to 1975, which is still a contemporary collection, thus the worry of temperature, humidity or air might not be so potent yet. But it will be soon. “I’d say: don’t be too hard on yourself as a young person excited about collecting. Care as much as you can to protect your things, be a good steward, but I’d say that what happens over time is that some of those things kind of work themselves out,” says Gates, “It’s good that you first get the object, and then you learn over time, and also together with the object, how to care for it. Keep asking questions and remain curious so that some of those good archival practices can be incorporated. In some cases it might be that you have to wrap the object in a paper bag or in a towel or towelette to observe the moisture. It’s not like you need to have a state-of-the-art Swiss stainless steel air conditioned situation! I think that there are modest ways to care for your things. So don’t be overwhelmed!”

Gates started to establish himself as an artist around 2010-2011 – a time when he also started collecting at a rapid pace. “At the time, it felt like the archive was the territory of white conceptualists, especially German conceptualists. In a way, the archive was born under the regime of the state, but if you look at the colonies around the world, they were using the archive to either ensure that certain things were in or ensuring that certain things were left out,” he says. “So the archive was a weapon of knowledge. History-making and archival productions are powerful tools. If you own and maintain your own archive, then you can determine what goes in it and what’s important for an 8-year-old to know, an 18-year-old to know, or a 90-year-old to know. In some ways, the early part of my practice was just ‘practising’ how to make information vital, and then, how to represent that information and create an output for that information, so that others might be interested.”

Today, ‘the archive’ is placed in both the background and the foreground in Gates’ work, as research behind his art-making, but also exhibited in its entirety – Gesamtkunstwerks, if you will. In 2016, he had just received a collection of 4,000 objects of ‘negrobilia’ – mass cultural objects and artefacts featuring stereotypical images of Black people – amassed by Edward J Williams and his wife as an attempt to take racist objects out of public view. He then got a call from the director of the Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria, Thomas Trummer, who asked him to have a show. “I thought, ‘What can I do with this archive?’” Gates recalls. “Austria has always had a very complicated relationship with outsiders and to the topic of race. Let me bring this archive, and have us look at it together! Let’s create a deep physical and intellectual encounter with this Black archive. Let’s confront them with the truth of Black radical intelligence and Black imagination. I wanted to inform them of the possibilities within racial differences.” Increasingly, creative practices include the importance of archive-making, leaving the territory of object-making and moving into the territory of institution-making.

How many things does Gates own? “If you counted a book as an individual object, there’s about 100,000-120,000 things, including albums, books and periodicals, but not including pots that I have made, or artworks,” he asys. “Aside from my life, I think we’re holding about 100,000 things. Yesterday I was at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and my colleague said that they have about 20 million objects! And every year, when they go on, say, a fishing expedition to look at regional fishing in a particular place, they gain another 100,000 fish to the collection of 3.5 million fish! Just in that portion of the Natural History Museum! I can’t say that I have that kind of ambition. But at the Natural History Museum, one is able to look at a swallow, a small bird, over the last 100 years from the same region. They see the effects of climate change by watching a flamingo’s colour change, and genetic transformation and migration patterns! I have respect for that kind of collection.”

What, then, is collecting for the 21st century? “In this digital world we no longer go to libraries, and we no longer sit with the objects in the same way that we used to a generation ago,” says Gates. “Algorithmic intelligence makes it easier and easier for a person to only understand, read or be consumed by things that they like. That can become very telescopic and narrow. These physical objects create new, unexpected, synaptic connections. And by being surrounded with beautiful things that also hold knowledge and memory, I maintain an investment in a wider position of the world. I’m interested in giving order to the things that come across my desk that pique my interest. By doing that, the object will represent a kind of self-portrait. In the end, what I have is a portrait of my interests, and who I am. I like that. Collecting as a kind of portraiture.”