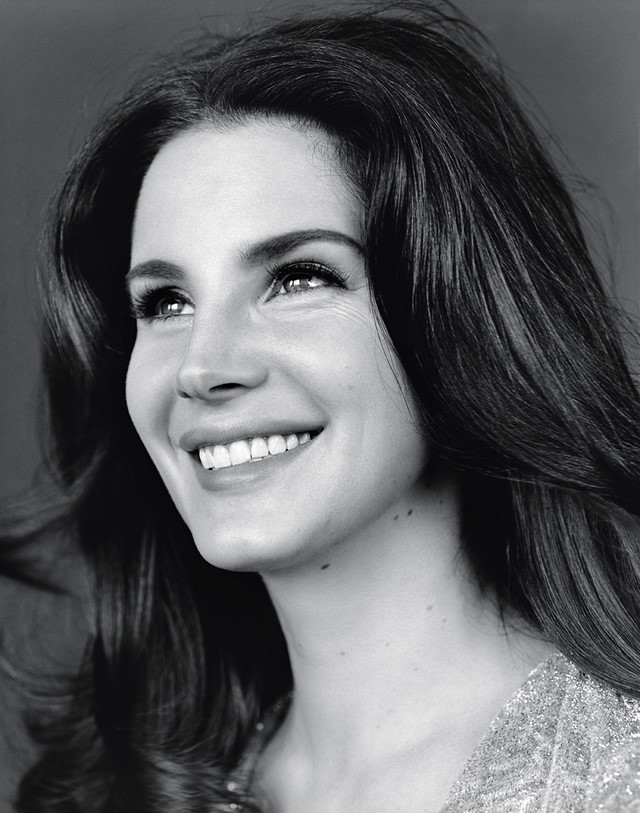

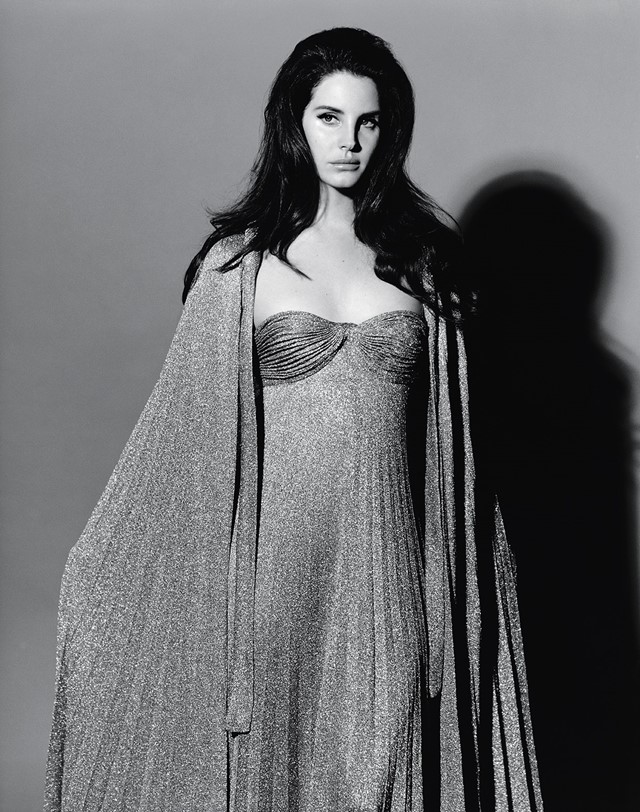

Here, we delve deeper into Lana Del Rey’s literary influences and what they reveal about her complex thoughts on love, freedom and America

In a seedy LA strip club, Lana Del Rey recites the Walt Whitman poem I Sing the Body Electric as she swings herself around a pole, cash tucked into her cherry red lingerie. The 1855 poem is concerned with the corruption of the body and the soul, closely mirroring the themes woven through Del Rey’s Biblical 2013 short film, Tropico.

Few contemporary artists deploy literary references quite as frequently as Del Rey. The singer, who released her own book of poetry in 2020, even has the words ‘Whitman’ and ‘Nabokov’ tattooed on her right arm in tribute to two of her favourite writers. Del Rey’s library is vast, stretching from Whitman’s 19th-century America through to works of more contemporary wordsmiths like Anthony Burgess and Sylvia Plath.

Here, we go on a journey through eight key literary references from Lana Del Rey’s discography that explore her complex concerns with love, time, freedom and America.

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

The text that most likely comes to mind when you think of Lana Del Rey is probably Lolita. While it would be unfair and inaccurate to blame the romanticisation of Vladimir Nabokov’s 1955 novel about child abuse squarely on her shoulders, if you were on Tumblr in the 2010s, you probably remember vignettes of heart-shaped sunglasses, bubblegum and cherries posted under #lolita and #lanadelrey. Del Rey often writes about relationships with older men and, in songs like Off To The Races, Lolita, Carmen and This Is What Makes Us Girls, she refers to these relationships by referencing Nabokov’s novel, misrepresenting it as a tragic, forbidden love story. Since her Born To Die era, these direct references have been retired, perhaps owing to their controversy. However, the girlish aesthetic of lollipops and frills lives on in TikTok’s coquette aesthetic, which is still enmeshed with both Lolita and Del Rey.

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

It’s easy to see why Del Rey might relate to Sylvia Plath. The two women are often conflated with their sadness and share a confessional writing style that touches on themes of mental anguish, turbulent relationships and the weight of being a woman. In hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have – but I have it, Del Rey casts herself as a “24/7 Sylvia Plath”. Plath has become a shorthand for depression, but the song also engages with her work on a deeper level. The refrain of “I’m not, no I’m not” mirrors Plath’s famous line, “I am. I am. I am.” Some fans have speculated that while Del Rey is relating her depression to Plath’s, she is saying that she will not meet the same fate, despite saying in 2014, “I wish I was dead already”.

I Sing the Body Electric by Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman is known for his subversive free verse poetry that mythologises the self and finds beauty in death; themes that run parallel with Del Rey’s own lyricism. He’s considered by many to be the first true American poet. In Body Electric, Del Rey sings that “Whitman is my daddy” while name-dropping Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe in the same song. In her vivid Americana landscape, pop culture icons and legendary poets are part of the same world. Until she deleted her account, Del Rey’s Twitter bio also contained a Whitman quote, “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself; I am large. I contain multitudes.”

A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennesse Williams

At the end of Tennesse Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire, ageing southern belle Blanche Dubois tells the doctor, “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers”. The line is dripping in irony because strangers have rarely been kind to her, unless in exchange for sex, but she still deludes herself into dreaming that this isn’t the reality. Del Rey references this “kindness of strangers” in Carmen and the Ride monologue, suggesting she sees a naivety in the hope for love and kindness that endures through her songs, despite the toxic relationships and objectification she writes about.

Howl by Allen Ginsberg

The Beat Generation, the post-war literary group including Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, is often referenced to denote freedom and nonconformity. In her songs, Del Rey sometimes depicts herself as a tumbleweed drifting up and down America like Kerouac in On The Road. In 2013, her Twitter bio read “Angel Headed Hipster”, a quote from Ginsberg’s generation-defining poem, Howl. Del Rey reads the entire poem in her short film Tropico while a group of women give a strip tease to leering businessmen and, in Brooklyn Baby, describes how she “gets down to Beat poetry”. The Beat Generation’s rejection of societal norms comes across and songs like Ride, Not All Who Wander Are Lost and Summertime Sadness reference American road trips, much like Kerouac and Ginsberg’s cross-country road trips in the late 1940s.

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

When Del Rey released Ultraviolence in 2014, she came under criticism again; this time, for romanticising domestic abuse. The controversial line, “He hit me and it felt like a kiss” comes from the 1962 track by The Crystals, but the song and album title originated in Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. The novel’s aggressive protagonist Alex and his ‘droogs’ consistently engage in what they call “a bit of ultra-violence”, meaning acts of extreme or excessive violence. But the song doesn’t reference the novel beyond the use of this word – Del Rey said she chose the title before writing the album because “I like the luxe sound of the word ‘ultra’ and the mean sound of the word ‘violence’ together. I like that two worlds can live in one”. In Del Rey’s music, love is often positioned alongside feelings of violence or despair. She writes about relationships that are obsessive and fatalistic, sometimes turning towards violence and abuse.

The Great Gatsby by F Scott Fitzgerald

Del Rey wrote Young and Beautiful for Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 adaptation of The Great Gatsby, but this isn’t the only way she has been inspired by the works of the Lost Generation, including F Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. Fitzgerald’s work homes in on the extravagant parties, glamour and faded dreams of the Jazz Age, unpicking how a shiny exterior isn’t always what it seems; there’s a sadness lurking beneath. The same could be said of Del Rey’s work, where glamorous imagery appears alongside emotional anguish. She alludes to Fitzgerald’s work in Tomorrow Never Came, Art Deco and Pretty When You Cry and references Hemingway in Money Power Glory and Religion.

Burnt Norton by TS Eliot

On the interlude of Del Rey’s third record, Honeymoon, she reads TS Eliot’s poem Burnt Norton, a philosophical contemplation of time. Honeymoon is Del Rey’s most sonically nostalgic record, with dramatic orchestral moments that hark back to old Hollywood film scores. Burnt Norton introspects over how the past and the future are always implicated in the present, a concept that feels pertinent throughout Del Rey’s expansive retro-lensed discography. She has always looked to the past while crafting a sound that has defined the contemporary era of alt-pop, combining the past and future into her present output.