As Sundance London brings the director to the capital this month, we present a guide to the cult cinema of LA icon Gregg Araki

One of the foremost proponents of the New Queer Cinema indie filmmaking movement of the early 1990s, LA icon Gregg Araki retains a huge cult following today thanks to his garish visuals, alt-rock soundtracks, game-changing queer characters, and endlessly quotable dialogue. It’s a fandom that has only intensified in the UK in recent years due to the fact that so many of his films also remain criminally inaccessible, even in the golden age of streaming.

True, more recent works such as sci-fi sex comedy Kaboom – the first-ever recipient of the Queer Palm award at Cannes in 2010, later won by fellow New Queer Cinema icon Todd Haynes (Carol) and, most recently, by Japanese master Hirokazu Kore-eda (Monster) – can be found without too much struggle. But by the time of that film’s release, Araki had already delivered a trilogy of left-field teen classics; a string of micro-budget independent works; and a masterpiece exploring the impact of child abuse – all of which have remained largely obscure hereafter.

Thankfully, that changes in 2023, as Sundance London brings the director to the capital this July for a masterclass alongside a three-film retrospective of classic works under the banner: ‘The Totally F*cked Up Cinema of Gregg Araki’. Among the screenings is a restored version of arguably his most legendary cult film, defiant teen crime classic The Doom Generation – while Mysterious Skin will also play on the big screen and at home via MUBI. 1997’s Nowhere, meanwhile, is set for restoration and re-release later in the year via long-time production partners Strand Releasing.

There’s no excuse to sleep any longer on these brilliant, heady, and youth-focused arthouse films – the works of one of the 90s most singular filmmakers, whose inimitable taste for kitsch costumes and pretentious props continues to inspire clothing brands and creatives today. Read on to find out where to start with the gaudy king of 90s gay cinema – whose totally f*cked up filmmaking remains as vivid today as it did a quarter-century ago.

The Living End, 1992

Described by critics as a “gay Thelma and Louise”, The Living End is an early Araki road movie concerning two HIV-positive queer men and their nihilistic journey in and out of Los Angeles.

Jack Daniels-swigging, pistol-swinging drifter Luke (Mike Dytri) is a smooth-chested hunk with nowhere to go. Film critic Jon (Craig Gilmore) is the shepherd who welcomes him into his home – which is full of pink Barbie cereal, inflatable Godzilla toys, and posters of The Smiths and Andy Warhol films. The garish props and outsider protagonists are memorable, but it’s Araki’s incredible use of colour (in his first colour movie) that takes the cake – with dustbowl orange deserts, electric blue road tunnels and neon 7/11 signs creating a vivid visual experience.

Produced on a budget of just $20,000, The Living End offers a highlight of the director’s “guerilla indie filmmaking” era – during which self-made productions were shot on the fly without permits, prompting regular interruptions by local authorities (indeed, the title sequence proclaims it ’An Irresponsible Movie’). Sundance audience members were reportedly outraged by an unprotected shower sex scene between the two protagonists – but the film was still nominated for the Grand Jury Prize.

Totally F***ed Up, 1993

If there’s a moment that best encapsulates the two-fingers-up mentality of Totally F***ed Up – ‘Another Homo Movie by Gregg Araki’, as it is introduced on-screen – it’s the scene where queer-curious Andy (James Duvall, Donnie Darko) monologues on the act of gay sex. “I do think butt-fucking’s totally gross,” he tells a handheld camcorder in flickering, lo-fi footage. “How can anyone put their dick where shit comes out?” The camera then cuts to a close-up, rear-view action shot from a hardcore pornography film – balls and buttholes front and centre.

Shot for “virtually no money” by Araki himself – who drove around Hollywood capturing sidewalk hangouts, poolside phone calls and gas stations at night with his core cast members – Totally F***ed Up stands up against the issues faced by gay teenagers at a time when the Aids epidemic and extremist politicians were stoking widespread discrimination. Across 15 vignettes, the film mixes queer confessionals with industrial rock and hardcore punk music – as bold fashion statements and sassy one-liners (“lick my love gun”; “gross-o-matic”) conjure up a vivid image of mid-90s outsider youth culture.

A $100,000 box office return hardly made it a hit, but it did resonate with those who caught it at Sundance and elsewhere – with Los Angeles Times critic Kevin Thomas placing it in his top ten films of the year list just below Pulp Fiction and Heavenly Creatures. Decades later, the film’s inter-title slogans, typography, and leading man would find a new audience – as Marc Jacobs and Ava Nirui featured them on a series of T-shirt designs via their Heaven label in 2020.

The Doom Generation, 1995

An aimless crime spree traverses an apocalyptic California wasteland in Araki’s expletive-laden counter-culture sensation The Doom Generation – which saw the director work with a modest budget ($800,000) for the first time in his career. It’s the story of a fatalistic ménage à trois of Rose McGowan (Scream), Jonathon Schaech and Araki muse James Duvall – who journey through subterranean clubs, soiled motels and desolate Quickie Marts with little regard for anyone but themselves.

Consisting on a diet of Doritos, Diet Cokes and cigarettes, the trio leave a trail of destruction as they navigate a world where ‘666’ appears on every street corner, and where clothes stores fly banners that instruct to “prepare for the apocalypse”. Indeed, this neon-soaked fever dream – rife with sex, swastikas and shoegaze – is remarkable for its excess, with catchphrases like “eat my fuck!” contributing to a requirement for 11 minutes to be cut to ensure an R-rating upon release.

After its Sundance screening was met with mass walkouts, Roger Ebert famously gave this “sleazefest” a zero-star review, likening it to a trashy Natural Born Killers. Today, Araki’s ‘Heterosexual Movie’ is considered a lowbrow cult classic – even if the released version was “butchered beyond recognition”. The acclaim will no doubt be furthered when the director’s newly-restored version – which restores previously-cut scenes and remixes the iconic soundtrack – debuts in the UK at Sundance London this week.

The Doom Generation is screening at Picturehouse Central on July 7, with the director in attendance.

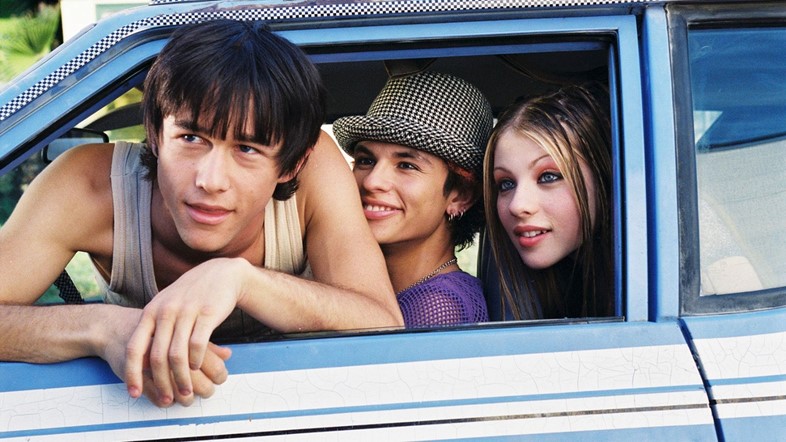

Nowhere, 1997

To understand the cult appeal of Nowhere, you needn’t look further than the reviews at the time of its release. “Completely lost up its own arse,” said Empire – effectively supporting The New York Times’ claim that this was “California’s version of Kids.” Paper called it “Clueless with nipple rings”, while the director considers it “Beverly Hills 90210 on acid.” In truth, it’s all of these things – and a kind of queer counterpart to Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused, too – which is precisely why a forthcoming restoration of the movie by Strand Releasing is such an exciting prospect in 2023.

The final entry of Araki’s ‘Teen Apocalypse’ trilogy takes place, as usual, in LA – where brace-faced students played by emerging superstars like Heather Graham (Boogie Nights), Christina Applegate (Anchorman), Mena Suvari (American Beauty) and Ryan Philippe (Cruel Intentions) amass opposite James Duvall on their way to a vibrant house party. With a mixtape soundtrack combining acts as diverse as Sonic Youth, Marilyn Manson, Blur and Future Sound of London, this hyper-colourful rodeo encompasses everything from drugs and kinky sex to televangelists and giant lizard men – eventually climaxing when a muscleman beats a drug dealer to a pulp with a tin of Campbell’s tomato soup.

A gaudy sensory overload, the film remains a lofty highlight of the director’s 90s filmmaking career. Unbeknownst to many, Araki filmed a mini-sequel in for Kenzo’s Autumn/Winter 2015 campaign, with Here Now packing a plethora of Araki staples into its modest six minutes: sloppy fast food, overblown dialogue, Slowdive, and an eye-catching wardrobe included.

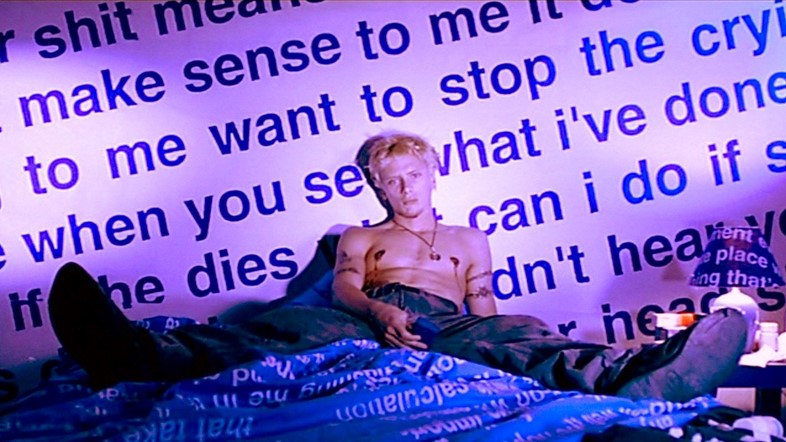

Mysterious Skin, 2004

In the summer of 1981, eight-year-old Little League player Brian Lackey becomes convinced he has been abducted by aliens after finding himself unable to account for five hours of his life. The same summer, teammate Neil McCormick is lured to his coach’s house with the promise of Atari video games and brightly-coloured Kellogg's cereal boxes. He is subsequently molested, repeatedly, by the paedophilic father figure.

A decade later, the boys are teenagers – separately dealing with the aftermaths of their traumas. As bespectacled dork Brian (Brady Corbet) investigates deeper into his past, he finds himself increasingly drawn to handsome rent boy Neil (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) – with their impending reunion pointing to a devastating truth.

Described by Roger Ebert as “the most harrowing and … touching film I have seen about child abuse”, this sophisticated and, at times, intensely uncomfortable coming-of-age movie is Araki’s undisputed masterpiece. Building on themes he had already been exploring for over a decade – queerness, alienation and nihilism among them – Mysterious Skin would see the director provide the essential missing link between Mystic River and The Virgin Suicides, with Harold Budd and Robin Guthrie’s blissed-out shoegaze score an ethereal sensory highlight.

Mysterious Skin is screening at Picturehouse Central on July 8, with the director in attendance. Also streaming via MUBI.

The Totally F*cked Up Cinema of Gregg Araki is part of Sundance Film Festival: London 2023, which runs at Picturehouse Central in London from 6-9 July.