In March 1942, Commando Micky Burn looked over his troop and had a “hideous shock”. He’d briefly caught sight of “Bill Gibson’s face”, he wrote in his memoir, and suddenly “knew he’d be killed”. The day before Operation Chariot, the most dangerous raid of the Second World War, Bill Gibson wrote to his father: “I can only hope that by laying down my life the generations to come might in some way remember us, and also benefit by what we have done.” Burn’s premonition was a true one. He was only 20 years old.

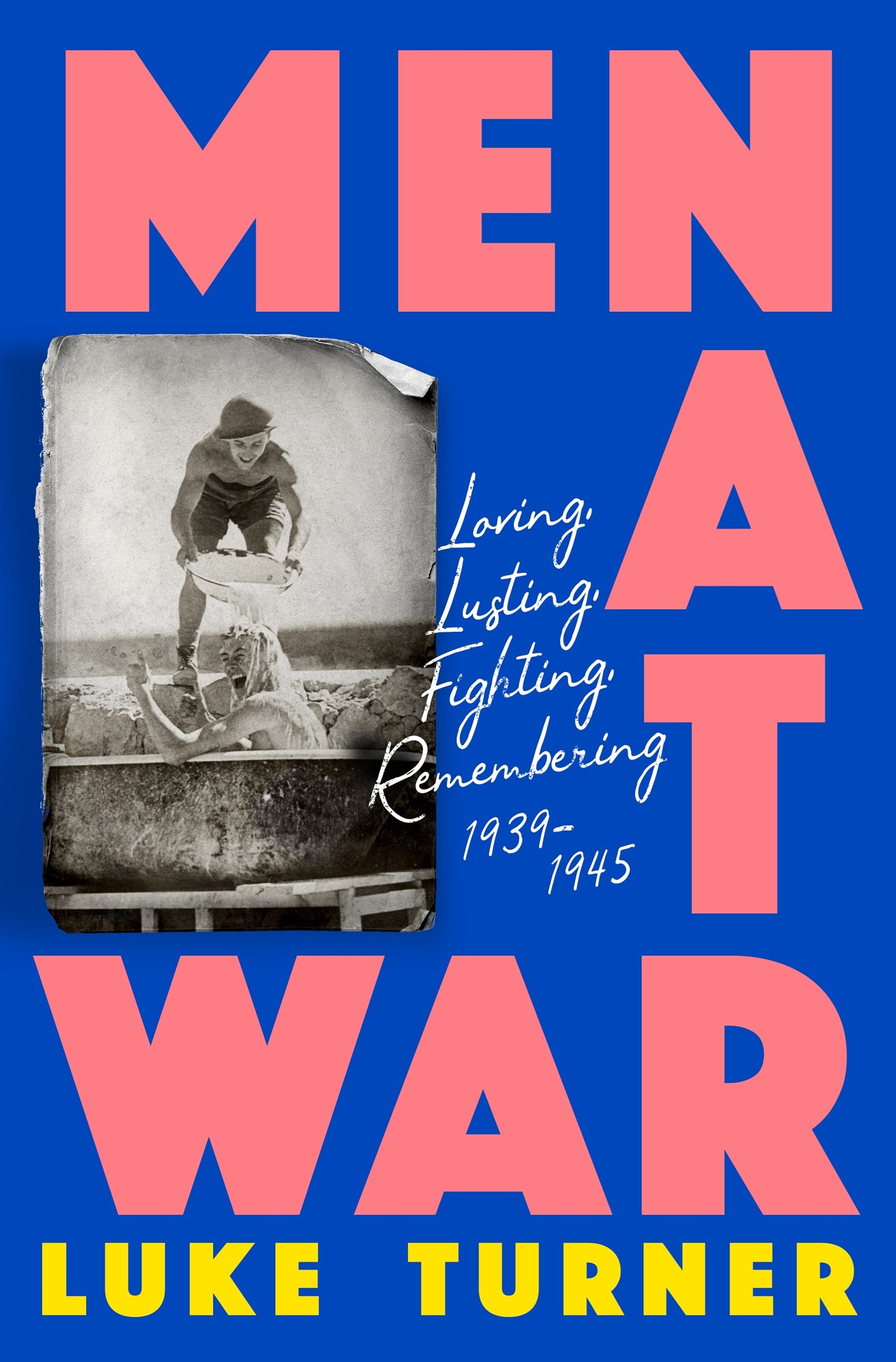

It’s the way we’ve remembered, and what we forget, that Luke Turner investigates in his new book Men At War. Following his acclaimed debut memoir Out of the Woods (2019), Turner strips away the cardboard clichés of those who served in the Second World War to discover who these men actually were. What follows is a complex portrait of the ordinary and extraordinary, of cross-dressing soldiers and queer sexualities; of affairs in blacked-out hotel rooms; and how, as Quentin Crisp put it, London “became like a paved double bed”.

Below, Turner sits down with AnOther to discuss his reasons for writing the book, why we should see past the binaries, choosing to blend history with memoir, and how the way we remember the Second World War is just as urgent today.

Tony Wilkes: You write at the beginning of the book about blowing open the “shallow, easy myths” of the Second World War and looking “behind the bunting”. Can you explain what you mean by that?

Luke Turner: In the past decade or so I’ve seen the memory of the war being taken over by the political right: in arguments around Brexit, Covid, even Conservative Party leadership campaigns. Those people are reducing the war to a very simple cliche and a very narrow view of the men who fought. So I wanted to write the book to say actually these men were not quiet heroes. They were very brave. But they were also very ordinary. And very complicated. They went through a very different experience to us but they weren’t very different. I wanted to look at the true breadth of their experience, and to include sex in that. I felt the thing that was always denied in our dewy-eyed nostalgia was any element of desire.

TW: What so striking about the book is the desire you mainly focus on is queer. And by doing that you show that manhood, that word “men” in the title, was actually much more fluid than we’re led to believe.

LT: Exactly. I really wanted to write about queer men but I didn’t want to write a “queer history book”. I didn’t want to silo queer men away because that’s what happened to them at the time. I wanted to say, “No, we’re part of masculinity. And let’s hold it all up together.” It was really important for me to do that.

There are very few physical documents of queer lives in the Second World War. But what has come to us from men who were openly gay, when they shared their experiences at least, was that the Second World War was a very fluid time for men sexually. That was something I found really interesting and wanted to write about.

“I wanted to look at the true breadth of their experience, and to include sex in that. I felt the thing that was always denied in our dewy-eyed nostalgia was any element of desire” – Luke Turner

I also feel that queer men have a more acute view of masculinity than their straight counterparts. Because we’re on the outside looking in. I’m a great believer that sexuality and gender is a fluid scale and we all move along it throughout our lives. And what I unearthed about the war really proves that. So any of these men didn’t fit into the gay or straight binary as it’s usually assumed.

TW: The book also has a fluid form of its own, part history and part memoir. Why did you choose to write it like that?

LT: I’m not a historian, so I was never going to write a traditional history book, and I think the relationship that we have in Britain with the Second World War is very personal. So I wanted to unpick that.

There are two aspects to the book: my own fascination with the war, and also being someone who isn’t heterosexual. I wanted to show that those two things don’t have to be separate. You imagine your average war enthusiast is some straight bloke over 50. And I sensed some resistance. We’re not meant to be into war as LGBTQ+ people. It’s not the done thing.

But I wanted to say, “No, let’s blur this a bit.” And the way to do that was writing about myself. I get so exhausted by the way everything is incredibly binary. I just don’t see the world in that way. Maybe it’s a lonely battle to be saying, “Hang on, it’s more complex” in these times. But that’s what I was trying to do.

TW: What most surprised you when researching the book?

LT: The most exciting thing I found was about the history of gender-affirming surgery. That pioneering work pretty much entirely comes from military medicine. It’s still used today. I write about Roberta Cowell who was an early if not the first woman to transition in the UK. And she had been a hardcore Spitfire pilot and a war hero and presented as extremely macho. And I write about how after she transitioned she was in a bar and this moustachioed bloke was trying to hit on her and going on and on about his wartime service. And she knew he was bullshitting because he got the technical details of the Spitfire wrong.

“There are two aspects to the book: my own fascination with the war, and also being someone who isn’t heterosexual. I wanted to show that those two things don’t have to be separate” – Luke Turner

TW: That leads nicely back to how the memory of the war is being used and abused. As the men themselves pass away, you write how this history is being exploited by political ideologies.

LT: I think we have got into a state of complacency that these wars won’t happen again. That the Cold War is over and that wars are distant, morally dubious things that happen overseas.

I was in Novosibirsk in Russia eight years ago and it’s a military city that was built during the conflict when they moved all the factories East away from the Germans. And there were soldiers with AK47s everywhere and the opera house is big enough to drive a tank through it for military operas. It’s a crazy place. And everywhere there was Second World War stuff. It was constantly on television. And all connected with Putin.

I felt this oppressive sense that something very sinister was stirring around the memory of the Second World War and it was being used to military and nationalists ends in Russia, and that’s just proved to get worse and worse. So it’s important to remember the Second World War in these nuanced ways because we don’t want to end up going down the same path as Russia has.

Now in this country, we have this right-wing myth of “Britain alone”. Every country thinks it won the Second World War by itself. It’s just like how the Battle of Britain is seen in the popular imagination as plucky Britain against the might of the German Air Force. In reality, the squadron that shot down the most German planes was Polish. Though the war is spoken about constantly, particularly in this country, there’s still a lot more to be discovered about it.

Men at War by Luke Turner is published by Orion, and is out now.