Until a few months ago, when writer Alissa Bennett tweeted about working on a new foreword for its re-print, I’d never heard of Ursula Parrott and her cult Jazz Age novel Ex-Wife, even though their combined lore seems primed for literary star treatment.

An account of an open marriage and eventual divorce taking place against the glimmering backdrop of parties, restaurants and one-night stands in prohibition-era New York, Ex-Wife was an instant hit, selling over 100,000 copies when it was first published anonymously. Later publicly connected to Parrott – who married four times, made (and spent) a fortune writing pulpy women’s fiction, and lived the end of her life hiding from an arrest warrant – the novel gave her both lifelong notoriety and the promise of being a subversive, generational voice she never quite fulfilled.

For fans of Edith Wharton and Jean Rhys – like Bennett herself, a historian of bad behaviour and, among other things, a former model, a director of Gladstone Gallery, co-host of The C-Word podcast alongside Lena Dunham, and admin of the Regret Counter Instagram – Ex-Wife is a kindred star. A younger cousin, maybe, to Wharton’s Gilded Age society girls, or how Rhys’ adrift women might have once begun, its protagonist Patricia is perched in the “chronological barricade” of New York between two world wars, a place, as Bennet says, of “strange public ruptures”.

Told with a polished Jazz Age dandyism, Ex-Wife resonates at a subtle but unmissable emotional frequency, which is what makes it feel so contemporary. While reading, I found myself taking screenshots to send to friends of almost every page, whether about “the preposterous sort of meal women order when they dine together”, watching oneself in the act of being left; “I hoped I looked devastated; I hoped I looked lovely”, or looking back on a relationship with no solution; “I thought of him kindly, as someone with whom I had shared a painful post-adolescence, someone who no doubt had been as bewildered as I about most things.”

Below, AnOther caught up with Alissa Bennett about why Ursula Parrott’s Ex-Wife still resonates today.

Zsofia Paulikovics: In your foreword, you write that when it was first published in 1929, the book was too scandalous, and when it was reprinted in the 80s it didn’t quite match up with the feminism of the era – but it seems to be in a moment of synchronicity now. Why do you feel that way?

Alissa Bennett: In the foreword, I talk about this book being published in a particular moment, wedged between Edith Wharton and Jean Rhys – probably my two favourites. Ex-Wife made Parrott a millionaire, it made her very famous, but it also really ruined her. She dragged the social pressures that piled upon her around forever, and I think it really tainted how the book was interpreted. And in the 80s, we looked at it and thought it was not radical enough, that its philosophies about what roles women were allowed to play were not in accordance with the era. I think that culturally now we’re more interested in introspection and emotional texture, and at this point obviously divorce is no longer verboten. When I read this book, it kind of freaked me out because I felt like my ghostwrote it. I felt like she was in my room. It was so, so, so familiar.

“When I read this book, it kind of freaked me out because I felt like my ghost wrote it. I felt like she was in my room” – Alissa Bennett

ZP: In the beginning of the novel Patricia says “I have never been as sure of myself since, as I was then, when I was 24.” I found that funny, because it speaks to that early twenties kind of confidence, while also being curiously ageless, or more tied to the act of being doggedly in love. Feeling like you can will the other person’s feelings into existence if you want it badly enough.

AB: And the fantasy that as a person you have this intrinsic value that you can force upon someone. When I read it, I was like, “Maybe all divorces and breakups are exactly the same.” There’s a universality in the experience when you read the book.

ZP: Another thing I found interesting in your foreword is the idea that the open marriage becomes “an asymmetrical failure”. Almost a century later, I wondered if open relationships can ever be anything but, if not failures, certainly asymmetrical.

AB: Imagine then the radicality of this gesture in 1929. I just read Marsha Gordon’s incredible biography of Ursula Parrott, in which she does a really compelling and complete sociological survey of how divorce escalated in the United States. By the end of the 20s, it was really skyrocketing, but you couldn’t get a no-fault divorce in New York, you had to go to Reno or Mexico. This is the time of the Hays Code, when Hollywood is controlling the morality of cinema, and this book comes out, and it’s like an atom bomb: not only about divorce, but about open marriages, about promiscuity, about drinking and one-night stands.

ZP: There’s a 2019 Paris Review piece on Ex-Wife that talks about the novel’s treatment of women as objets d’art. The depiction of the clothes, the make-up, the facials, even the interiors is fascinating … Patricia says at one point “[men] were not real. Neither was the office. Clothes were real.” And I thought, “Yes, exactly!”

AB: In the foreword, I write about Patricia spending her whole cheque on Chanel, or Helena Rubinstein, or buying Vionnet dresses that she can’t afford. I remember reading it, and just thinking, “It’s what we do.” Exorcising pain by ornamenting your exterior. Which is the amazing thing also when you look at Ursula Parrott’s life: that is exactly how she lived. She died in absolute squalor, there was a point at the end of her life when she was living on the subway. Her work commanded amazing figures through the 30s; she wrote a book that was adapted for the screen, for which she got 500,000 dollars. She made something like 50,000 dollars or more on a serialised novel. And all of it gets poured back into her artifice. Her deep connection to glamour, in the etymological sense.

ZP: After Ex-Wife, Parrott went on to produce a number of pulpy romance novels and films, with titles like Say Goodbye Again and Let’s Just Marry. With genre fiction, there’s often an assumption that the author is unaware that their work isn’t high literature. Do you think that she was in on the joke?

AB: I don’t think so. I think that she lived beyond her means for many years, and her work was reduced to this cheap, formulaic, automatic kind of writing. And for 15 or 20 years, while she’s churning out this romantic literature, she keeps saying, “I have another serious novel in me”. She was always in debt, she had the IRS breathing down her neck, she was always late turning in copy. It was cheap and I think she knew it was cheap.

I was talking to Gary Indiana once and I said, “I love Horse Crazy so much, it’s one of my favourite books”, and he said, “Do you know how painful it is when someone tells you that your first book is the best?” That was her life.

“This book comes out, and it’s like an atom bomb: not only about divorce, but about open marriages, about promiscuity, about drinking and one night stands – Alissa Bennett

ZP: I really loved the idea of a piece of work being produced not with the goal of “I want to be an artist”, but purely because of her being in a psychological bind. It’s emotionally driven.

AB: It’s interesting also because of the genesis of the book. Peter is her first husband, Lyndesay Parrott, and then she met this guy, Hugh O’Connor. She loved him. He was married but wouldn’t leave the wife; they had an affair for many years. They were at a New Year’s Eve party in 1928, and he started telling people that she was gonna write a novel. She was working as a copywriter for a fashion department store at the time. And he was like, “Now that I’ve told all of these people you have to write it.”

It goes back to when we were talking about wanting to keep someone. Like, what do I have to do to show you that I’m worth keeping around? So she writes Ex-Wife. And I don’t know if it’s a condition of youth, when you’re able to walk through that fire and it all goes into the pages, but the relationship tortured her for the rest of her life, yet she could never replicate thinking, ‘if I can do this maybe I can get him’.

ZP: I’m interested in Parrott's personality later in life and all the scandal that came her way. I wonder if she felt that there was a need to keep people talking, to keep that interest.

AB: Oh yeah, I think [there was] a great need. Also, if your first great success hinged on all these things, there’s probably always the impulse to go back there, to replicate it. It’s repetition compulsion. That really ends up being the most corrosive agent in her life: this attempt to get back to the feeling she had when she wrote this book. She was married four times, all disastrously, many for less than one year. And I sort of related to that too, because I remember when I was younger, thinking, “How do you produce good work if you’re happy?” As an older person, that’s like when people think they have to drink to write. It’s a fantasy narrative that you put in place. But she did this consistently throughout her life.

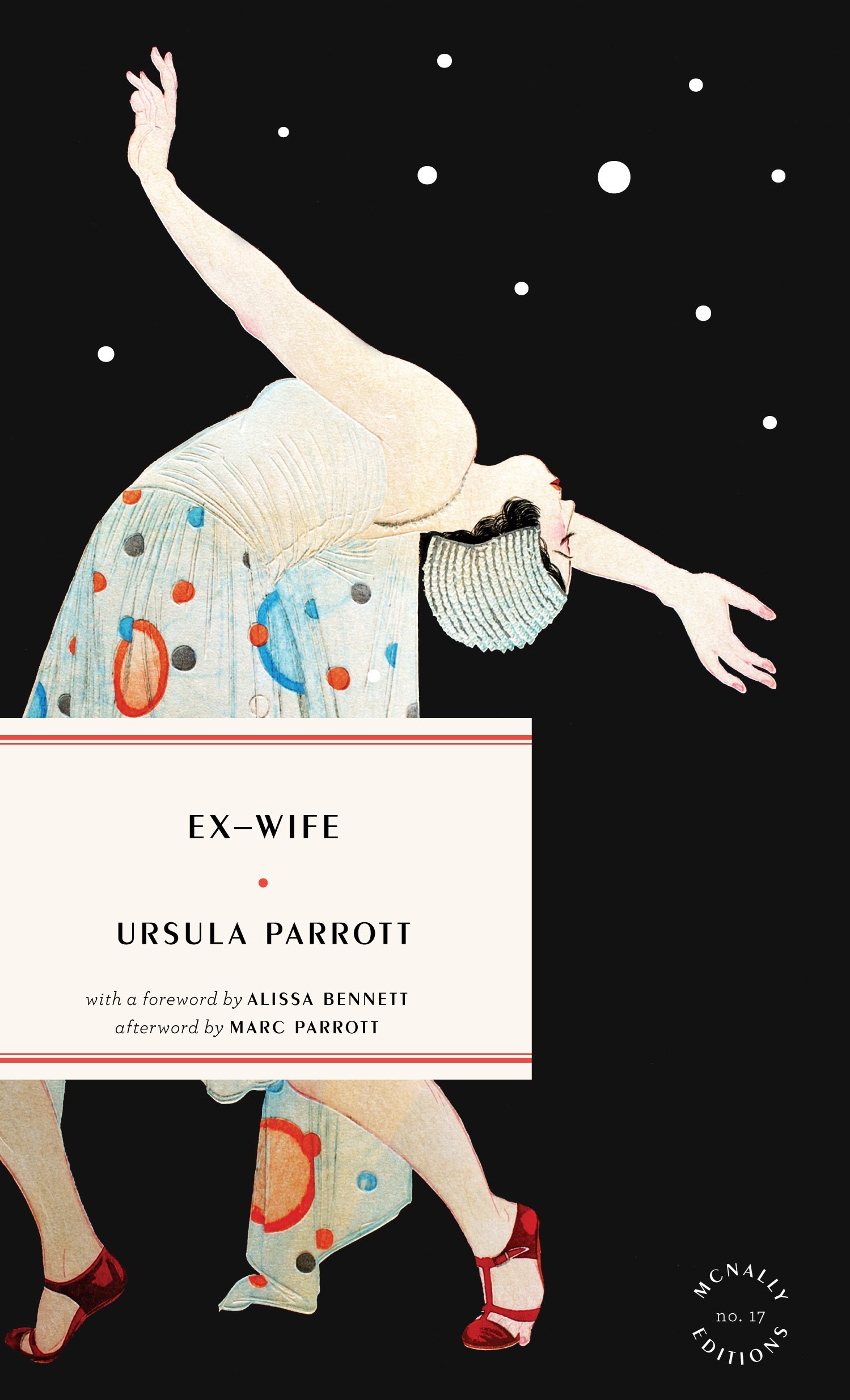

Ex-Wife by Ursula Parrott is published by McNally Editions and is out now.