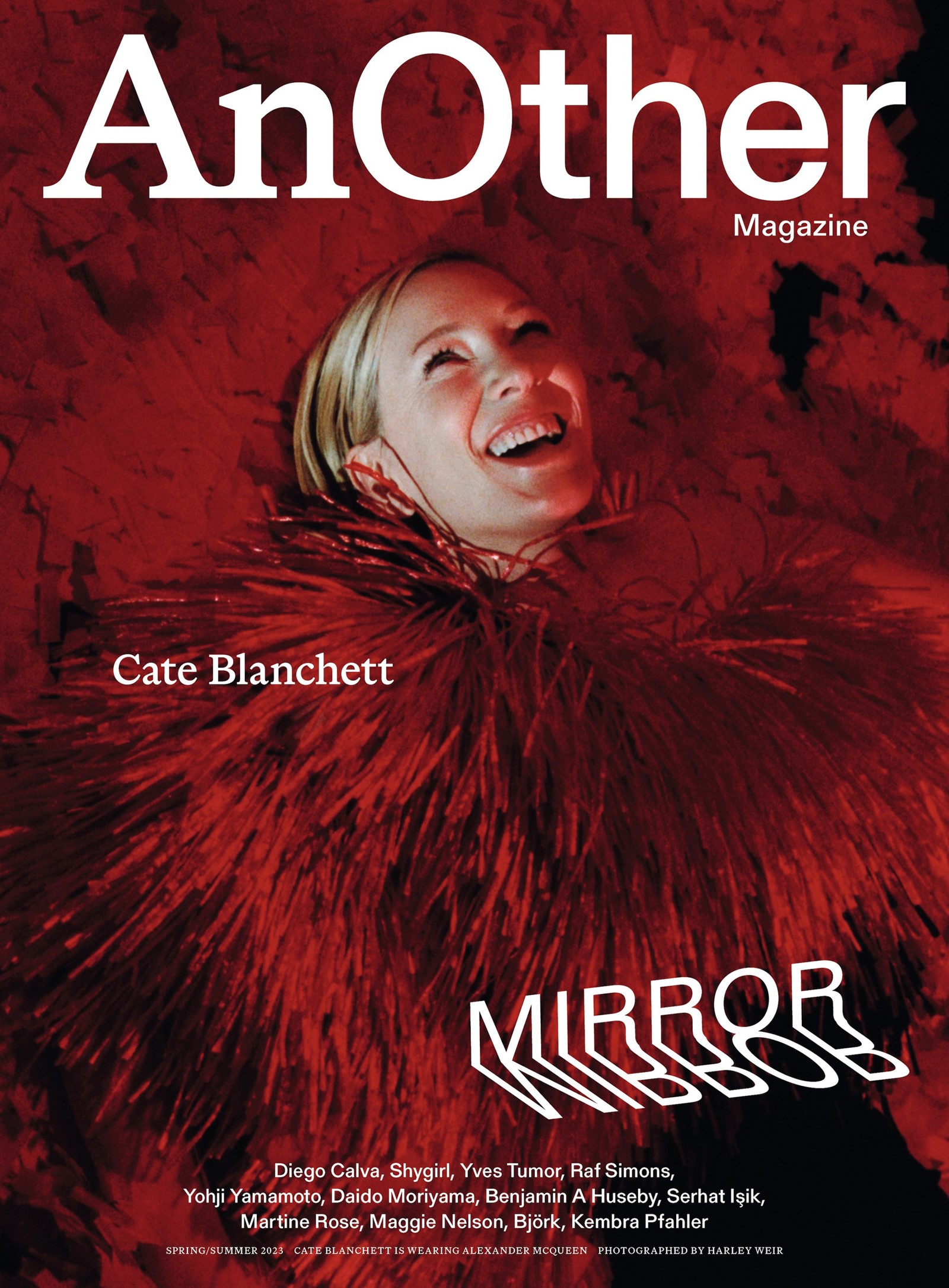

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Cate Blanchett: I’m an enormous fan. Let’s just get that out of the way right now.

Maggie Nelson: Stop it. No, I can’t believe you want to even be here on the Zoom with me, but that’s very nice of you.

CB: Well, it’s so interesting to talk to you about this film because you innately understand all the grey areas. I think I struggle with screened narrative sometimes because the idea of narrative often derails the more complicated aspects of the endeavour. It’s as if we go into a maze, or a labyrinth, and we are trained to expect a minotaur in there. I’m not the person to judge what I make – as actors we just do what we do and it’s for other people to interpret. And there’s no right or wrong way to interpret anything, let alone a film. But people have got bound up in the narrative with Tár, which is quite enigmatic and elusive. And Todd [Field, the film’s writer and director] has deliberately not given the audience a definitive answer to anything, but it’s been fascinating to me that certain adjectives have been levelled at the Lydia Tár character and the situation. I’ve thought, “Oh wow, OK, I didn’t think any of that.” But then it’s irrelevant what I think.

MN: What you say about narrative is so interesting – not only with this movie but also more generally – that we’re supposed to be taken through all these nuanced places and then receive a message at the end that makes sense of them. We’re supposed to find, as you say, the minotaur. It reminds me of how, in writing, you can’t really escape narrative – even in experimental, non-narrative writing – but there are a lot of options for delivering the sense of having had a worthwhile aesthetic experience that isn’t necessarily narratively driven.

CB: But even if you are writing in a fragmentary way, is it just that we’re driven as a species to try to order and make sense of it? In a way, narrative exists because people yearn for a path, or we’re taught to make pathways or connections. That’s what I struggle with in the film because it’s very much a process film – that’s the ‘narrative’. It’s a journey, or a musing, or a poking around, rather than an arriving or landing. There are a lot of opposing ideas that are held within the film simultaneously, which is why it is ambiguous.

MN: And it’s probably why you get so many people throwing out unexpected adjectives, because the film acts as kind of a Rorschach test. I had dinner with a friend the other day, a writer, and she was like, “I just felt like it was a whole movie about trying to take away this woman’s power. She was so powerful and everyone wanted to chip away at her power and take it from her.” It was yet another reading I hadn’t heard before. Then I thought about the particular ways in which this friend is powerful and talented, and I was like, it makes a lot of sense she would feel like that’s what she was watching.

CB: So, Maggie, you teach, right?

MN: Yes, at the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles.

CB: And how are you finding the university system now?

MN: I love teaching, I really do. And that was an interesting angle on the movie – to watch it thinking about the work of teaching, of mentoring, of identifying and developing talent, and of course, the circulation of power. Some of it felt painfully familiar and some of it was obviously next-level, nightmare stuff. I’ve taught almost every semester since 1999 – a long time now. I thought a lot while watching the film about how you can grow accustomed, as a teacher, to the fact that students bring a lot of their baggage to you, projecting onto you and so on, but you sometimes forget that you are bringing all your stuff to the classroom as well. Hopefully the longer you do it, the more aware you can be of these dynamics, the less swept away by them you can become. Anyway, I don’t feel like the young teacher any more, which feels like a good thing.

CB: Well, it’s certainly very difficult to find a forum in which those nuanced, complicated discussions can take place. It’s like people don’t want to expose themselves to potentially dangerous, or truly dangerous, ideas. And we alight in less-interesting directions – me included. And you wrote this amazing thing – I’m going to misquote you – that the search for narrative and morality actually flattens the experience. Maybe it’s speaking to the inadequacies of our education system, but we look to cinema, or to novels, to teach us history, to teach us how to think, how to be.

“This is the thing about people in powerful, unassailable positions – and those who are responsible for placing them there, keeping them there and benefiting from that – they’re often very magnetic and attractive” – Cate Blanchett

So we impose a literal search for ‘truth’ onto a fictitious enterprise, which is strange. Our relationship to it seems foreign to me. I mean, I never knew I wanted to be an actor, but I knew I didn’t want to sit in one place. My only ambition when I left high school was to travel with my work. I didn’t know what that work would be, but I had a sense of that Martha Graham restlessness.

I love keeping ideas aloft without having to pin them down. And that we make sense of them in ways that are not always conscious or digestible through language. Sometimes you make a film, or you write a novel, and you can reduce it to an easily digestible paragraph for people as an entry point. And then sometimes you make, or are involved in, work and you don’t want to get in the way of an audience’s experience. But then there’s that opposing tug – “Well, if I don’t talk about it to a certain degree, then no one’s even going to see it.” So suddenly you enter a dialogue that is fraught with potholes and missteps. And then before you know it, you’ve been reduced anyway.

MN: Yes, which is very odd and frustrating. It’s especially weird when you write whole books that take the time to say everything exactly the way you want to say it, with all the attendant nuance and complication, and you still find yourself getting drawn into reductive conversations. I can only imagine how hard this is as an actor.

I write about art a lot – I’m putting together this book of art essays right now – and someone asked me the other day, “Why do artists always want writers to write about them? Why are they not content to just let their work speak for itself?” And I was like, “Because it’s a service to translate the work across mediums – it gives the work more cultural capital, and it also grants a certain kind of legibility and opens up new angles on it.” Artists need that, though sometimes they understandably hate it – so they ask people like me or other writers to do it, whom they hope and pray won’t reduce them or give only a dry art historical reading or a catty review.

That question of what to do when you yourself are called upon to translate what you did in a movie in which you’ve acted seems to me incredibly difficult. Especially when everyone will be hanging on to every word you say about it.

CB: Or the idea that you are meant to have a definitive grasp on what it is …

The process of making something is entirely different from what happens in post. Of course, I was involved in that, being really close with Todd and being a producer on the film, but in the end it doesn’t have any meaning at all until an audience enters the auditorium. They complete the meaning. But I wonder whether there’s some self-censorship happening with this film. I remember my mother really wanted to see it. I said, “OK, just go in with an open mind, Mom.” And she said, “Well, people aren’t going to like her.” And I thought, maybe they won’t want to like her.

Todd wanted the whole thing to feel fly-on-the-wall. And I hope you feel so inside her psyche that you are experiencing and seeing and witnessing things that the character is almost unaware she’s doing – things that perhaps we’ve fantasised about enacting ourselves, or dreamt of, or consciously decided to do the opposite of because we’re good people. In a way I had no sense of judgement of her whatsoever, but I think there’s something about her we don’t want to admit to in ourselves. This is the thing about people in powerful, unassailable positions – and those who are responsible for placing them there, keeping them there and benefiting from that – they’re often very magnetic and attractive.

MN: That was one of my favourite aspects of the movie – its lens on how power circulates everywhere. People use the word power as if it’s intrinsically a bad thing, but as good students of Foucault we know that power circulates everywhere, in institutions but also in intimacy. We know that there’s power in parenting your children, or in caretaking elders, and so on. I was very interested in the scene with the neighbours, who are living in this squalor, where the mother – or perhaps sister, it’s not quite clear – eventually dies in a way that seems horrifying, perhaps abusive. That situation would certainly involve power, but it’s obviously hyper-complex, in that we aren’t sure what their options are, or what the relationship has been. We also know that while caretaking is a form of power, it can also be a form of servitude. There can be all these different forms of power and abuse and scarcity and care going on at the same time.

With the Krista character, too – clearly Tár’s blackballing of this person is problematic, for reasons that will become clear if you see the film. But there’s also the vexing fact that being in a position to recommend someone or warn against them is always fraught, especially if there are legitimate reasons why you can’t recommend them, reasons why it would actually feel unethical to do so. Then there’s the power circulating in love and attraction, be it requited or unrequited, which usually involves a lot of moving parts and shifting roles.

“[Tár] definitely brings up the scary fact that no matter how well we think we know other people, or how competent we think we are at judging character, other people are essentially uncontrollable and unknowable” – Maggie Nelson

So much of our lives can be spent figuring out to whom we’re attributing power as much as who has the power in the first place. Recognising what our agency is in these power attributions and where we don’t have agency in them. I thought the movie was very effective at running a lot of those scenarios at the same time.

CB: It is a very confronting thing, admitting where we give our agency away. Sometimes we do that in small, incremental ways and sometimes we do it carelessly. We certainly do it in a compulsive way when you fall in love with an idea or a person. But with Krista I was thinking about Tár as a person who prides themselves on their impeccable judgement. She had made a bad judgement call about someone. She had let her guard down. I never allowed myself to say whether there had been some sexual connection with her because it didn’t feel, in this instance, important to pin down. You can be enmeshed with someone without physical contact – you can be psychologically enmeshed.

So there’s a line when Tár says, “She wasn’t one of us.” And there are a thousand ways in which I suppose you could deliver that line but there was a sense of, “I made a mistake.” I remember someone was talking to me about a young sculptor who was incredibly talented, and his benefactor was saying, “I don’t know that he’s a genuine artist.” And I said, “What do you mean by that?” And he said, “I don’t think he has a sense of longevity. I don’t think he can weather failure.” And I think that, in a way, we’ve all had moments of massive inspiration, but if you live your life as an artist you must be able to be brutal with yourself and weather intense failure. Success in a lot of ways reveals who we are, but you don’t learn much from it. You learn far more from failure. Tár made a misstep with whatever happened with Krista, a misjudgment about her character, and then felt she had to extricate herself from it. And if your identity has been built on having impeccable judgement, or any other quality, and you make a fundamental misstep in that direction, then you start making the decision – from whatever lobe in your brain – to avoid confronting it. You then become increasingly estranged from yourself. In a way, that moment is extrapolated out for the rest of the film – you are dealing with someone who is grappling with failure.

And she’s a perfectionist. And perfectionism is just a stick you can beat yourself with – you can find fault with anything. Tár certainly finds enormous fault with herself.

MN: I like this angle on Tár – that she’s tortured by a misstep in judgement, that the thrill and sometimes horror of being in relation to others is that we can’t know everything there is to know about other people. You can only know as much as you know. The movie definitely brings up the scary fact that no matter how well we think we know other people, or how competent we think we are at judging character, other people are essentially uncontrollable and unknowable. They can always surprise us, and – scarier still – we can surprise ourselves!

I also had a question – it felt important in the film that the Russian cellist to whom Tár gives her attention is an extraordinary player. As opposed to, “Oh, I want to get in this girl’s pants and she sucks but I’ll give her special treatment because she’s attractive to me.” It made me feel like, however flawed Tár’s interpersonal judgement is or isn’t, there is still this question of the natural injustice of merit, of talent, of ability. The injustice that there is somebody that’s better than others at this particular thing and that she is going to get picked out and elevated for it, and that it might seem unfair because Tár seems to have the hots for her, but even in the blind audition, the Russian cellist prevails.

There is a certain weak formulation that leads us to ask questions like, “What’s worth it for great art?” The stronger formulation, it seems to me, starts with admitting to the force that great art sometimes entails – the great concentration or commitment or otherworldliness or sometimes callousness to other demands – and then asking how we are going to negotiate that force in a world in which there are so many other demands on one’s devotion and attention.

Well, especially as women and mothers, we want the fantasy that we can be absolutely everything at all times to everybody and still serve whatever power and talent we feel we have. Sometimes this works out, but sometimes it’s not so clear-cut. In coming to talk to you today, I thought about this question a lot because you, also, are a very talented and very powerful person. You have this force moving through you – this force that is so much bigger than ourselves. We may or may not even know why we have it or what to do with it, but there it is, in a life.

Feminists and women have taken very different tacks to this issue. For example, when I got the MacArthur ‘genius’ grant [in 2016], I noticed in all the interviews that everyone really wanted me to weigh in on the word genius – to say I didn’t believe in it, to disavow it, etc. This has a long and important history, especially in feminism – it’s been important to deconstruct the myth of individual genius, as that myth has been constructed in such a way as to exclude certain bodies and minds from its terms. (See, for example, Linda Nochlin’s famous 1971 essay, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?.) And so, understandably, a lot of people who get that award say, “Oh, I don’t call it that, that’s not the word for me.” But I kept thinking about Gertrude Stein, who loved the word genius and uses it throughout The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas, and I started to wonder what it would be like if I just said, “Oh, I think it’s a great word for me. I totally think I’m a genius.” Not that I feel like that – it was just an experiment, to see what would happen if I didn’t spend time and trouble trying to deflect the word.

CB: But those words have incredible weight. So, because that word is put in your in-tray, you’re forced to deal with it. You’re forced to have an opinion on it. So if it helps me circumnavigate this thing quickly, then I’ll say, “Yeah, sure, that’s fine.” But it’s irrelevant to me.

“After we finished, Todd ... just put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘You shouldn’t work for a while.’ Something had happened to both of us through the process of making it. If you’re lucky it happens once, maybe twice in your life ... but this was the process of encountering one another and it was all-consuming” – Cate Blanchett

When you’re in flow, you don’t think about technique, you don’t think about labels, you are just in the middle of the tempest, and you are flying and moving, but then you’ll hit a hump and then you need technique and experience and labels to keep moving. But often we create from a far less literal place. Back to what you were saying about the power of talent – it’s a kind of sorcery. It can, in a way, overtake more susceptible individuals. I think that relates to someone like Krista who gets caught up in the situation and is not able to navigate that – and there’s no judgement in that because I think not everyone can or wants to.

But certain people have an ability and are enlivened and enriched by being in the middle of that tempest, and other people are depleted by it. And in the often-difficult environment of a profession wrought with insecurity and instability and personal confrontation and failure and occasional success, perhaps you need to be able to weather that storm and actually enjoy the instability and be fed by it. I find it hard that people often assume – and I’m sure they do with you, in terms of the extraordinary things you write – that it was ever going to be thus.

MN: Right. And it’s not.

CB: It’s just not. I think we can retrospectively make a narrative about somebody’s creative life, but it never happens in that linear way. And because the film goes inside the maelstrom of the creative process, people reduce that to a simple, moralistic, judgmental narrative. I’m left thinking, “Wow, I’ve really failed there because that wasn’t the endeavour at all.”

MN: I don’t know that people are making that reduction about the film, which I think is good. There’s a problem, though, in what you were describing before, about looking for platforms to discuss grey areas. I wrote a book [in 2021] called On Freedom, and I noticed over and over again that even if you studiously avoid catchphrases that aren’t meaningful to you – like ‘cancel culture’ – the media, to propagate itself, just wants to say them anyway, it wants to treat cultural production as if it’s saying whatever the media wants it to say. Sometimes it doesn’t even matter what the thing itself is or does. But the good news, at least for a writer – and hopefully this applies to films too – is that one can learn to disassociate the moment of publication from one’s experience of the book, because the book will hopefully live on, and people can come to it whenever and have whatever opinion about it in new, changing contexts, and they won’t be wrong.

CB: I feel the same way about the film, but at this point in the process it’s in your inbox. And you must answer it because it’s a catchphrase – it’s like an advertising slogan that we all must have an opinion about.

MN: I had the good luck of not having any substantial readership until I was about 42 – I’d written eight books before I wrote a book that a lot of people cared about. And that was lovely because now my other books have been republished, but in my mind they were never any less than the book of mine that got more attention, The Argonauts. I don’t even think that’s my best book. My point is that I’ve seen how books that were, say, rejected by 27 publishers, can be revalued as good and important on the simple caprice of time and market. It reminds me that the moment of acceptance or publication or release is just a moment to get through, it is not necessarily that movie or book’s cultural life.

CB: Well, after we finished, Todd, who has become a dear friend, just put his hand on my shoulder and said, “You shouldn’t work for a while.” Something had happened to both of us through the process of making it. If you’re lucky it happens once, maybe twice in your life – it’s happened to me in theatre and it’s happened to me a couple of times in film – but this was the process of encountering one another and it was all-consuming. And I said, “Oh yeah, you’re right, but I’m just about to work with Alfonso Cuarón ... I’m committed to that for six months.”

But there was a real wisdom in that because we’re all part of this constant output, and it’s like, would she please shut the fuck up? Just be quiet for a while. It’s such an important part of the process.

“As women and mothers, we want the fantasy that we can be absolutely everything at all times to everybody and still serve whatever power and talent we feel we have” - Maggie Nelson

And that’s what I also love about Hildur Guðnadóttir’s score, that in its absence it’s as powerful as its presence. The film has an invisible strength thanks to the parts of the film that Todd has chosen to excise – all those things he decided he didn’t want in the film exist there homoeopathically.

CB: We think about our output and our achievements and the things that people really want to talk about, but in terms of a process and the life of someone who makes things, it’s also about stepping away and percolating. The work continues to happen there. And that’s why when I first read the screenplay I thought the ending was deeply tragic. It’s a real descent. But in the performing of it, it was absolutely exhilarating because I felt it was breaking beyond the canon of, not only the things that a musician should be playing and making and experiencing, but also about her own inner judgement. She had been released from all of that to find out what would happen next.

MN: She really loves conducting and at the end she is still conducting, and having an emotional experience with that. And it seems to me that a group of dedicated cosplaying fans are ready to have a grand experience with the music as much, or more, than anybody in a stodgy Upper East Side concert hall.

CB: You will never see anyone asleep at a cosplay convention. But it reveals the lenses we choose because the circumstances we know about, not only the character I play but all the characters, aren’t finite. Todd and I were hoping that we could somehow just drop this little gem and generate some interesting conversation. Conversation that would probably be fierce and passionate, that people would come at from all different perspectives. We hoped people would see it in the cinema where the ideas could stay big and a little bit elusive.

Hair: Robert Vetica at The Wall Group using ORIBE. Make-up: Mary Greenwell at Premier Hair and Make-up using ARMANI BEAUTY. Manicure: Shigeko Taylor at Star Touch Agency using PATTIE YANKEE PRODUCTS. Set design: Patience Harding at New School Represents. Digital tech: Pamela Grant. Lighting: Jonnie Chambers. Photographic assistants: Johnny Tergo and Milan Aguirre. Styling assistants: Isabella Damazio, Karolina Frechowicz and Niki Ravari. Tailor: Hasmik Kourinian. Hair assistant: Brandon Mayberry. Make-up assistant: Brittany Leslie. Props assistants: Emahn Ray and Bradford Schroeder. Printing: Artful Dodgers. Executive producer: Kimberly Arms at Partner Films. Producer: Richard Polio at Partner Films. Production co-ordinator: Jonathan Gilcrest. Production assistant: Alicia Portales. Post-production: Output London

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally on 23 March 2023. Pre-order here.