When we speak over video call Constance Debré is in Paris, in an airy apartment with high, corniced ceilings – “but it's not my place.” She has recently returned from a stint in New York, then LA; she loved LA in particular, and apologises early on for her English. I tell her that, to me, she seems more or less fluent-perfect, but as I come to realise, Debré is invested in the power and precision of language, so ‘more or less’ is inadequate for her purposes. She considers beauty, for instance, very important, but as she clarifies, “To me, beauty is not pretty. It’s something which can, not support, but indulge, violence, suffering, cruelty, everything.”

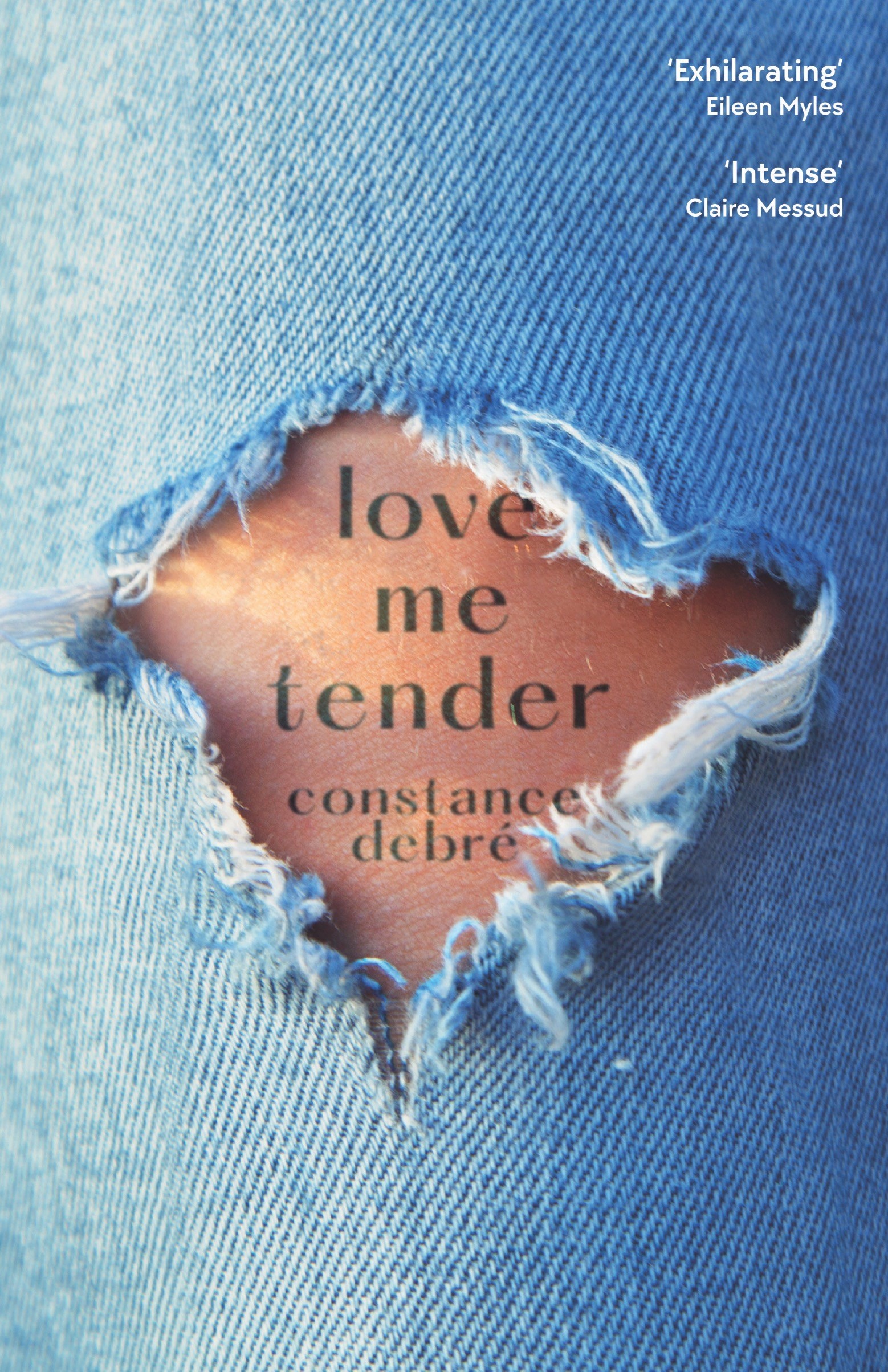

Debré is already a sensation in her native France, where her notoriety may stem in part from perceptions around her ‘esteemed’ family. “I’m very sorry to mention it,” she says, “but because of my name – because my grandfather used to be a prime minister like 50 years ago – they get excited about it.” This month sees the UK publication of her 2020 novel, Love Me Tender, translated by Holly James. A startling, unsentimental and very moving account of the brutal custody battle over her then eight-year-old son – the ‘I’ of the novel and Debré can be treated as interchangeable – it offers a version of motherhood outside of society’s prescribed ideals.

Love Me Tender is striking for its ambiguity. The swaggering, assured confidence of its ‘I’ voice, that sits brilliantly and humanly, against the fact that its position, on love and other things, is constantly being revised. In life, Debré similarly has both a complete conviction in her work and opinions, and a provocative, outlaw sensibility, but also the intellectual curiosity to keep editing and revising even as she is talking. It can be hard to keep her and the novel separate in your mind. Towards the end of our conversation I find myself asking, as if turning the last page of Love Me Tender and looking for more information, “Do you see your son now?”

Holly Connolly: I’m interested in the way other writers may have shaped you, in particular Guillaume Dustan. I could feel his influence in that reiteration of the ‘I’ and the creation of self through aesthetic and there are some biographical parallels too; he was an administrative judge from a respected family before he began writing.

Constance Debré: The first thing is that my taste in literature and the books I read are more classical than contemporary, and it’s normal to compare my writing to other contemporary writers, and of course they matter, but not that much. Except probably for Dustan, you are right, especially for Love Me Tender, because I was reading him a lot at this time.

But I think one of the answers, in terms of inspiration, is not in other books but is in law, and in my legal past. Especially in French case law, which is very different from British law or US law, in that it is very much about language, about a very precise, simple, clear and effective use of language. To me, it's so beautiful. And so I have this very simple, clear, cold, direct style of writing.

HC: It can be tempting to think of your writing as a clean break from your past as a lawyer, whereas in reality that’s perhaps not the case – there’s a lot of overlap.

CD: Absolutely. Another thing is, there's the legal style of writing, and of using language, but there is also the fact that I used to be a defence lawyer. In that role, you have to grab the judge to get a decision, and words have to be effective and not pretty because it’s all about violence, something is happening here. Language is an event, it has to become an act.

I really detest this French bourgeois way of making books, showing at every page that the writer has read Roland Barthes and [Baruch] Spinoza, which we all have done, of course, but we don't have to show it. One of the reasons I love books and literature is because [of] language – it’s the thing we all have.

HC: How easy did you find it to write a novel – can I call it a novel? – that draws so closely from very painful parts of your life?

CD: Yes, it is a novel. I mean, everything is true, and my life is the material of it, but it's not about my life, in a way, because I wanted to build a character, and I had certain ideas about the characters. For certain writers, [when] writing in the first person and using their lives, the goal is to find a truth about what happened in their lives or the truth about themselves, which is absolutely not what I am interested in. The question of identity is not at all something I am interested in.

“One of the reasons I love books and literature is because [of] language – it’s the thing we all have” – Constance Debré

HC: Some people have framed Love Me Tender as this queer identity novel, which I was surprised by – I didn’t really read that in it.

CD: You're absolutely right. The queer thing is a huge misunderstanding of my book. I mean, I am a lesbian, and it's in the book, there’s no question about it, but it’s not about that. But it’s the first thing people see, so they just say ‘the character is a gay woman, so it’s about that, it’s about identity and queer identity.’ Well, no actually. I had in mind, it’s an old way of seeing things, the Greek one, where you have, say, Ulysses, just this guy who is a hero because he’s defying the gods and so he has trials all the time, but it’s because of the trials that he is a hero. Once you see your own life this way, or for instance, what happens in Love Me Tender, as trials sent by the gods – well, I wouldn't say it’s fun but it has its own kind of beauty. There is a [Charles] Bukowski quote: ‘what matters most is how well you walk through the fire.’ I love that, and we can use it for everything in life.

HC: I watched a video of a talk you gave with Eileen Myles, and you had a brilliant line: ‘I don’t like to write about feelings, I like the reader to feel the feelings.’ Can you talk about creating literature that is experiential?

CD: I don’t like to talk too much about feelings. I don’t deny them at all, but especially in books I think it can be very embarrassing. More than that, when you talk too much about feelings they disappear. I think art in general, and books in particular, are there to make us feel things.

I don’t want people who read my work to be convinced that the character or myself is great. I want them to be taken by the book and sometimes moved, sometimes angry, shocked and embarrassed. This is what I want when I read a book, or watch a movie, and keep thinking about it the day after, and this is the sign that it’s interesting. I want my book to do something to people, so it would be useless to say ‘I am sad’ or ‘I do love my child.’ Feelings can make for very bad literature.

HC: I don’t think I’ve read a better account of the fear of a prescriptive model of motherhood than Love Me Tender. I loved this part: ‘I was going to do it my way, without the absurdity that comes with being a woman, the obscenity that comes with being a mother.’ It reminded me of Marguerite Duras’ writing on mothers too.

CD: This was one of my ideas before the book. We all have a mother, and many people have been a mother, and in literature it doesn’t exist. Or if it does, it’s just so boring. You can maybe say, ‘Well it’s not always easy …’ But that was not really my point. I wanted to look at another way of being a mother, another way of loving a child. There was some defying attitude in that, yes.

I think it’s very strange to see that once you become a mother, there are many things you could have escaped before that, from so called heteronormativity, that suddenly are there. It’s very funny to see all those young parents acting as parents, the women; two months ago she was just a girl and then suddenly it’s, ‘Oh! I’m a mum!’ What are you pretending to be? Those things are just ugly and ridiculous and full of lies, and full of violence as well. And we know that a lie produces violence and that families are full of violence. So what are all those people lying about, why are they lying? Because, of course, there’s so much anxiety. But maybe we can talk about it clearly, because there is also something true – there is also love.

“I don’t like to talk too much about feelings. I don’t deny them at all, but especially in books I think it can be very embarrassing” – Constance Debré

HC: Being a parent to Paul is presented as something which is also freeing. You write: ‘I might never have become a lesbian if I hadn’t been his mother first.’

CD: Love in general, romantic love too, is something that can diminish us, it can put limits on what we want to be and what we want to do, and then we are angry at the other person. But it can also give us so much strength. Having a child … you cannot lie. If you hear the false tone of your voice when you talk to your son, and decide then to tell the truth, suddenly you cannot lie to yourself about many things. You come to really love the truth and to believe in it.

There’s also a great pleasure in talking to a child, because at some point this little animal begins to talk and listen and then you have to present the world to him, because he doesn’t know anything. You have to explain everything and then you realise that you have an opinion on the world. It’s very exciting.

Love Me Tender by Constance Debré is out in the UK now.