From Akira to Crazy Thunder Road, Japan’s delinquent biker movies gripped post-war Japan. Here, James Balmont unpacks the legacy left in their tracks

Revving engines and rebellious attitudes are hallmarks of any decent motor-fetishising counter-culture. But in mid-20th-century Japan – a nation steeped in the lore of samurai warrior philosophies and renowned (at the time) for industrial and technological advancement – a subculture of biker gangs became so vividly disruptive that they were allegedly the country’s number one source of juvenile delinquency. The press dubbed them bōsōzoku (literally “running-out-of-control tribes”), and their wild legacy would inspire all kinds of vibrant visual media across the decades.

Biker gangs first emerged in Japan following the country’s destruction at the end of World War Two, as military veterans including non-deployed kamikaze pilots struggled to adjust to post-war society. With many still harbouring ultra-nationalistic tendencies and striving for adrenaline and community, the streets soon became a forum for subversion and new ideas at a time when American occupation was bringing films like Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and The Wild One (1953) into the country. As the likes of James Dean and Marlon Brando became icons, greaser fashions like leather jackets, steel toe-caps and jellied quiffs were reappropriated to form the crux of a new subculture.

By the late ‘60s, following the unexpected success of Roger Corman’s 1966 biker b-movie The Wild Angels, Japanese studios became alerted to the potential of a new sub-genre – and began putting their own delinquent biker movies into production. Toei studio’s Delinquent Boss was one such success, but it was Nikkatsu studio’s Stray Cat Rock series that cemented the female outlaw biker movie as a cinematic sensation.

The first film, 1970’s Stray Cat Rock: Delinquent Girl Boss, serves as a fitting introduction. A female biker dressed in double denim races across the asphalt in the opening shot, surrounded by male riders in leather jackets and shades. As they weave in and out of traffic, chaotic camerawork soaks up disorientating views of Tokyo, while the sounds of burning rubber fill the audio field.

Ako (Akiko Wada) and the Stray Cats gang – led by the tassel-jacketed Mei (emerging icon Meiko Kaji) – engage in knife fights in the street and stunt-laden bike chases thereafter, with 60s psych-rock and hippie fashions accentuating the film’s rich sense of style. The film was such a hit that it spawned four sequels in barely a year, as a new cinematic trend took the nation by storm.

Directors like exploitation king Teruo Ishii would deliver their own grindhouse variations on the formula as the decade went on, with 1976’s Detonation! Violent Games – a violent and bloody riff on West Side Story in which motorcycles are used as weapons – a notable example.

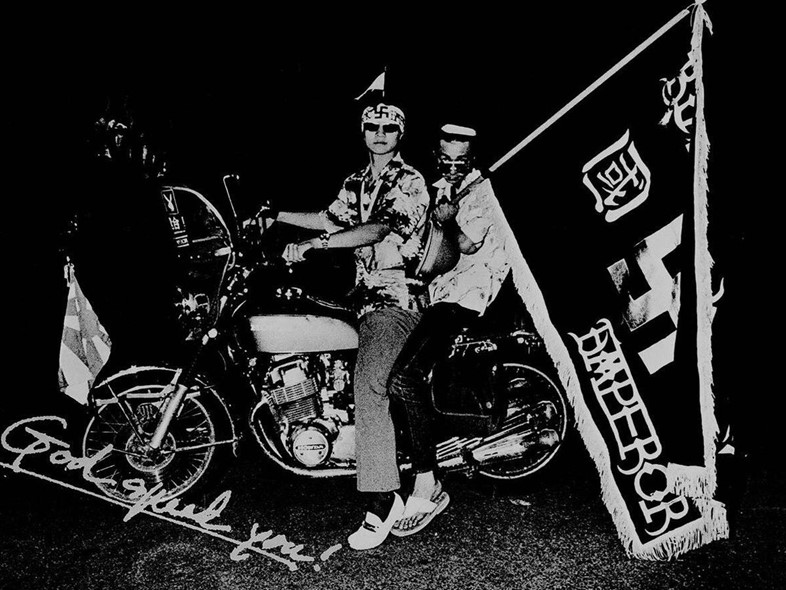

It was that same year that arguably the most important documentary film on Japan’s real-life biker gangs was also released. Mitsuo Yanagimachi’s black-and-white 16mm feature God Speed You! Black Emperor (the inspiration for the Canadian post-rock band of the same name) remains an obscurity in the west, but is an essential historic document that also highlighted a developing trend in low-budget, independent filmmaking.

The film follows the real-life Chiba Black Emperor gang – a bōsōzoku faction marked by their strict governance, tight infrastructure, and a bold visual identity that includes bandanas, shaved eyebrows and the use of the swastika as insignia. They’re introduced with footage of a real-life confrontation with authorities before the engines fire up and a storm of bright headlights fills the screen to the sound of searing guitar riffs and drums.

While this posturing defines the evolution of the subculture, even more revealing is how the film captures the young members’ lives behind the scenes. At a large indoor gathering, new recruits discuss their backgrounds: they’re almost all jobless, working-class boys under the age of 20, looking for a sense of community and identity. “I live in a tunnel. No home,” says one; “I’ve never been to school,” says another.

The bōsōzoku subculture reached its peak in the early 80s, with membership rising to an estimated 42,500 members across hundreds of gangs in metropolises all over the country. They were, by now, widely recognisable for their custom Suzuki, Kawasaki and Honda bikes, featuring bent-down handlebars, huge seat-backs, decals bearing tribal insignias, and flying colours like the famous rising sun flag.

Wearing boots, boiler suits and bandanas – dubbed tokkō-fuku, meaning “special attack uniform” – they roamed the streets wielding baseball bats and Molotov cocktails on weekends, causing public nuisances and engaging in violent turf wars. Their association with Japan’s notorious crime syndicate, the yakuza, reportedly became so pronounced at one point that up to one-third of yakuza recruits were coming from bōsōzoku gangs. In a 2015 documentary by Vice, meanwhile, one former gang member recalled that being a bōsōzoku member was “like being in the military. It was like being drafted into war.”

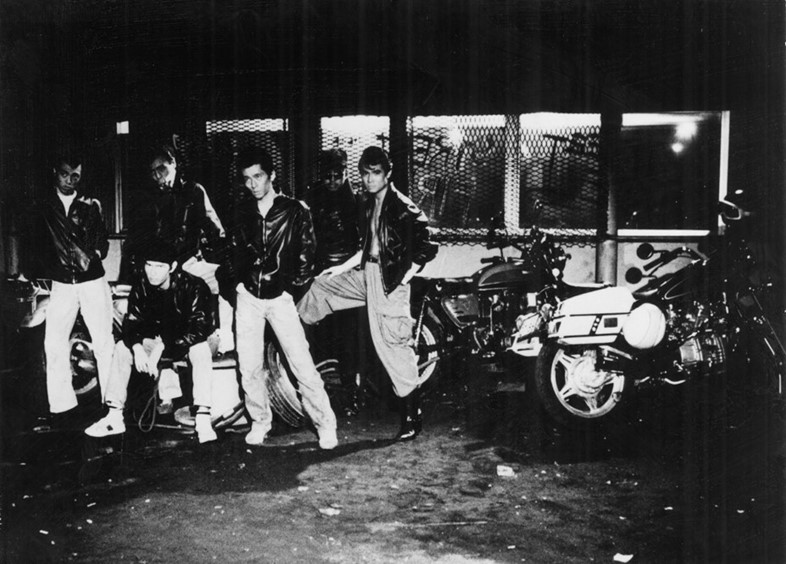

The sentiment was not lost on independent filmmaker Sogo Ishii, who, in 1980, utilised his school’s 16mm cameras to create the pioneering dystopian thriller Crazy Thunder Road. With inspiration taken from the 70s punk movement, and the ferocious biker gangs in Tokyo and elsewhere, the film might be seen as a Japanese counterpart to Australia’s Mad Max – another biker-fuelled dystopian action film, itself inspired by the raw violence seen at Australian gas stations in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis. Set in a dilapidated near-future wasteland, Ishii’s biker battle royale even featured real-life bōsōzoku members as fired-up extras. “We had no choice — we didn’t have any bikes ourselves,” he told Dazed in 2022.

Crazy Thunder Road was such a singular and energetic piece of work that major Japanese studio Toei opted to pick it up for nationwide distribution – launching Ishii’s scintillating director career straight out of film school thereafter. It also laid down the groundwork for Japan’s vibrant and cerebral cyberpunk subgenre, which frequently fused the flesh of man with twisted scrap metal in science fiction stories that warned against the dangers of new technologies.

One of the most prominent of these films, of course, was the global anime sensation Akira (Katsuhiro Otomo, 1988) – itself heavily influenced by the real-life activities of the bōsōzoku, who are depicted in the film as rebellious clans within the lawless metropolis of ‘Neo Tokyo’.

The bōsōzoku would even arrive in Hollywood around this time through films that bore similar aesthetics. Just a few years after releasing his own cyberpunk masterpiece via Blade Runner (1982), Ridley Scott delivered Black Rain (1989), a macho and somewhat racist blockbuster starring Michael Douglas as a bike fanatic detective who journeys to Japan after becoming embroiled in a yakuza conspiracy in New York.

The film opens with Douglas’ character engaging in a testosterone-fuelled drag race beneath the Brooklyn Bridge, but it's Japan’s biker gangs who make heads roll later on. They’re a recurring source of intimidation in violence on behalf of their yakuza buddies in Osaka, showing up wearing bandanas and bearing flags down neon-soaked back streets, embodying what had clearly now become stereotype.

More sympathetic explorations of these rebellious bikers could be found in Japanese cinema by this time, as well. Nobuhiko Obayashi – director of the psychedelic horror cult classic House in 1977 – would deliver a prime example in 1986, via the romantic melodrama His Motorbike, Her Island. Like the aforementioned Crazy Thunder Road, it is released outside of Japan for the first time ever this year via cult distributors Third Window Films.

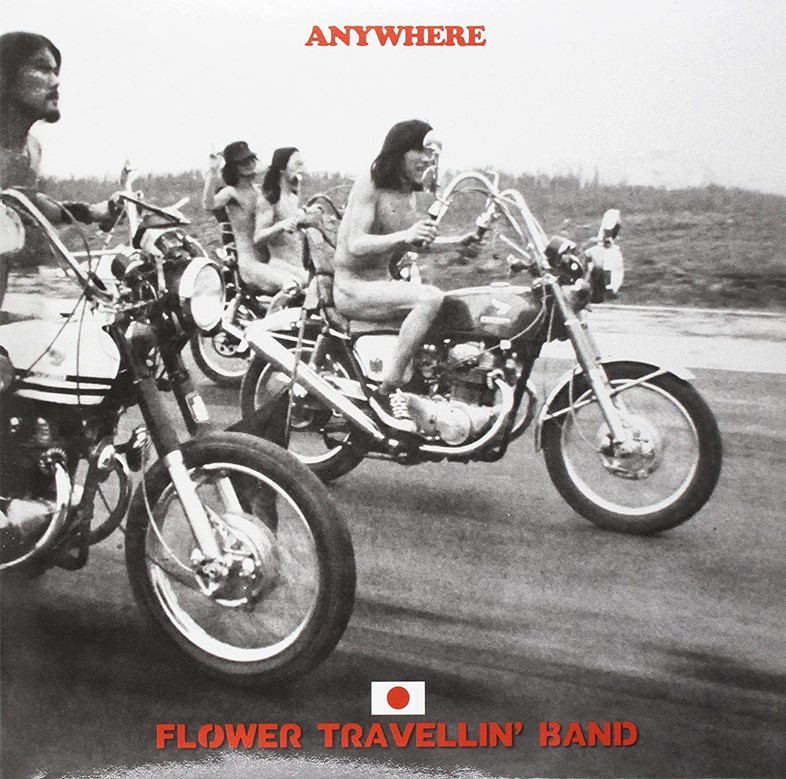

The tale of a loveable rogue (played by future straight-to-video icon Riki Takeuchi, famed for his pompadour hairstyle and zany roles in the works of Takashi Miike) includes naked bike riding and gauntlet duels atop speeding motors – but Ko’s beloved blue-and-black Kawasaki W3 is more of a symbol for freedom than anarchy. From the opening shots, in which the camera fetishises the bike chassis in close-up as the engine gently purrs and rumbles, the bike is a beloved object that brings Ko in touch with the resplendent natural surroundings of Japan’s countryside as well as stoking a blossoming romance.

By the ‘90s the bōsōzoku subculture was already in decline. With the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble (the foundation for three decades of economic stagnation thereafter), there was less disposable income for the gangs’ signature bike modifications. Police crackdowns, fresh legislation and new surveillance technology since the early ‘00s have further limited the bōsōzoku presence and influence on visual culture, as other kinds of juvenile delinquency cinema would cause a storm instead.

They didn’t disappear entirely. In an article titled ‘Motorcycle Gangs Ride Roughshod in Japan’ in 2000, The Telegraph reported a notorious case in which a dentist lost an eye after being attacked by a Tokyo biker gang during a robbery. The culprits were three boys aged 16 and 17. But documentaries like 2012’s Sayonara Speed Tribes, which follows “an ageing Japanese bike gangster and the crop of halfhearted youngsters he mentors” would, nonetheless, paint the bōsōzoku as a dying breed.

By 2017, fewer than 6,200 members remained in Japan. But the subculture has endured as an inspiration on everything from Harajuku high street fashions to contemporary arts and media, with manga series Tokyo Revengers one of the most popular vessels of contemporary biker fiction with over 65 million copies in circulation as of July 2022 (it’s also been adapted to anime and live-action film).

Whether the engines will continue to roar for much longer remains to be seen — but with a visual legacy as dynamic as this, it’s safe to say the bōsōzoku have left a vivid impression in their tracks.