There is a recurring joke in Heidi Sopinka’s new novel Utopia: Paz, a young artist working in LA in the late 1970s, explains that she is quitting smoking and drinking “because women artists don’t make it until they are old”. Her gag is barbed with contempt for the art world’s misogyny, but it also contains a sad truth: Romy, her idol, has just died under mysterious circumstances, leaving behind an unfinished and overlooked body of work. Paz finds ghostly traces of Romy everywhere – first, she discovers her journals, and then postcards with her sketches are delivered to friends around the city. As she retraces Romy’s footsteps, Paz sees how the art world has never really made space for either of them. (Just as Paz tells her own “women artist bit,” the men in her circle have one too – “Riddle: why haven’t women made great works of art? Answer: because they are great works of art.”)

Like the real-life feminist artists Ana Mendieta, Hannah Wilke, Adrian Piper or Judy Chicago, Paz learns to celebrate making work outside of the system – work that cannot be commodified and that rejects the capitalist, patriarchal organisation of the art world. For Sopinka, a writer and designer who also wrote about women and art in her debut book The Dictionary of Animal Languages (2018), these artists used their bodies “as a tool or a material, and so having nothing for sale made it by nature anti-capitalist and feminist as a result.”

From her studio in Toronto, Sopinka spoke to AnOther about paying homage to the feminist art movement and galvanising creativity for something collective, angry, and hopeful – for worlds not yet realised.

Tia Glista: The novel is dedicated to the feminist artists of the 1970s, like Ana Mendieta, Judy Chicago and Hannah Wilke, and many of the characters’ work or lives bear similarities to these real-life counterparts. What do you think it is about their work from that period that still speaks to many of us so strongly?

HS: There’s something that is so the opposite of what we are in, in a sense. Being in a digital age, we are so disembodied, you know? In terms of their work, it’s just so visceral, raw, bloody, bodily. It also truly feels like work from a pre-digital era.

TG: How did you undertake the research on this period? Was it always intended as fiction?

Heidi Sopinka: I did a tonne of reading and I watched some documentaries. I was in touch with Ana Mendieta’s niece who is trying to finish a documentary. I always knew that I am not the best historian, so I am probably not the best person to write a definitive book about them, but I really loved the notion of circumnavigating the legacies of men when it comes to art. I thought, if I use and am inspired by these women’s work and lives, then I would add a level of imagination and fiction to it to posit them in a story that I could grapple with myself.

“Being in a digital age, we are so disembodied, you know? In terms of their work, it’s just so visceral, raw, bloody, bodily. It also truly feels like work from a pre-digital era” – Heidi Sopinka

TG: Speaking of embodiment, Romy often expresses her ambivalence about gender, and later on, there is an implication of gender nonconformity. Can you talk about writing her fascinating relationship to the body?

HS: The epigraph of the book is “the body is not a thing, it’s a situation,” which is Simone de Beauvoir. Now we have all this language around gender identity but at the time [of second-wave feminism] it was really limited, and the movement itself was such an essentialist thing that limited women in so many ways because the definition of woman was so limited. Gender is such a societal construct and Romy’s really aware of that but doesn’t really have the language for it, she just has the feeling of it … and she’s also aware that we don’t all carry the same experience of inhabiting our bodies, and everyone is managing a different level of risk. I think by nature of doing body works, you just absolutely start to really question what a body is, and your own relationship with your body, I guess.

TG: I was really drawn to how you write about the desire to lose the material body, of women courting ghostliness and dissolution. It seems like an effect of being erased by the male gaze, but also wanting to evade it. And it’s also about a wish to give up the physical form, too – to become boundaryless. Is this a feeling that you relate to?

HS: All of those themes are so close to me! When I was writing this book, I went through early menopause in my early forties and at the same time, my eldest child is a transgender person. And so I’ve been thinking a lot about gender abolition and gender anarchy and the constraints of the body. My child just wants to sort of live in the cloud and not have a body and oddly, I have this similar sensation. I feel like men get to sort of feel like they don’t have a body, but women, or the category of people who are assigned the material conditions of women, are always reminded of their body. It was a huge part of my thinking and I tapped into it, also around body works and, as you mentioned, ghosts. I guess I don’t believe that on one side there are ghosts and on the other side there’s the undead, sort of like the dark matter in the book that gets brought up by the Romy character – everything exists everywhere all at once. It’s like the notion of not having to live in a body would be this sort of genderless, borderless place that I wanted to hint at and go into a little bit.

TG: I feel like this also extends to Romy and Paz’s shared love of flying, and then I learned that you were once a pilot? Is this true? What made you want to bring it into the book?

HS: I weirdly got my pilot’s license after I finished university. I worked as a bush cook on forest fires in the Yukon-Alaska border, and we got flown in in helicopters, and I remember I just had this feeling like going off a cliff – just like, “This is an incredible feeling.” And I started to talk to the pilots and understood that they did sort of six weeks or eight weeks of really intense, dangerous work and then that was their pay for the whole year. I thought, “This is the perfect thing to have as a writer!” You could just do this and then write weird stuff that didn’t need to make money for the rest of the year! It’s also a space where, though it is a heavily male situation in terms of flying and being around planes and mechanics and everything, once you’re up in the air, it is just so freeing, in a way that just sounds so cliched, but it truly is just you and the controls and the air.

TG: Speaking of freedom, at one point, you write: “With [the baby] Flea on her lap, [Paz] feels a shift from the belief that freedom and responsibility are opposites. Her desire for freedom, she now sees, has been the desire for a distinctly male kind of power that has always been unavailable to her.” What is Paz – or the book – saying about freedom?

HS: For these women in the book and in that time – and frankly, still in our time – it was sort of about finding ways to live without being limited, damaged, or even destroyed, really, by the violent reinforcement of ideas of what is possible for the kind of body you have to live inside. Particularly, I wanted to explore motherhood, art, and freedom because I think that being a mother and still making art involves absolutely opposite parts of your brain: one is the selfish part, and the other is totally selfless.

I think the characters are realising too, as you mentioned in that passage, that they are defined by a male definition of freedom and that women will never be free if the term of freedom is embedded in the patriarchy – it has to be a different version, it has to sort of be a disruption of that. The notion that actually being committed to another human or to your work is a kind of freedom, it’s sort of self-defined, I think … spending time with a baby, the patriarchy says, is not the stuff of art. But I like the notion of thinking, “Well, maybe it is.” I don’t really have an answer per se, but more just an exploration of the notion that we have to sort of self-define our own freedoms because it’s been given to us in a very particular way that doesn’t work for women.

“I feel like men get to sort of feel like they don’t have a body, but women, or the category of people who are assigned the material conditions of women, are always reminded of their body” – Heidi Sopinka

TG: The book is called Utopia, obviously. Can you talk more about that idea – what does feminist utopia mean to you? What can writing about it do?

HS: I was really interested in utopias because we are so in a dystopia, and the whole pandemic has been a dystopia, and I really loved the notion of looking back at a time of second-wave feminism and first-generation performance art when anything seemed possible. Because of performance being new in that period, it wasn’t male-dominated, which meant again, that there was not the limitation or restrictions or competition with the past – which means with men’s work. So I loved the notion of women making work freely and exploring what that would look like. And then on the other hand, it’s sort of a bit couched in the notion that it was a failed utopia – right after that were the 1980s, which couldn’t have gotten further away from all the things that the women were fighting for then … failed revolutions still have good ideas, even if a lot of it doesn't make for permanent change. I wanted to draw the throughline from the 1970s to now in some ways, in the hopes of showing that women and lots of people have done a lot of this work for us.

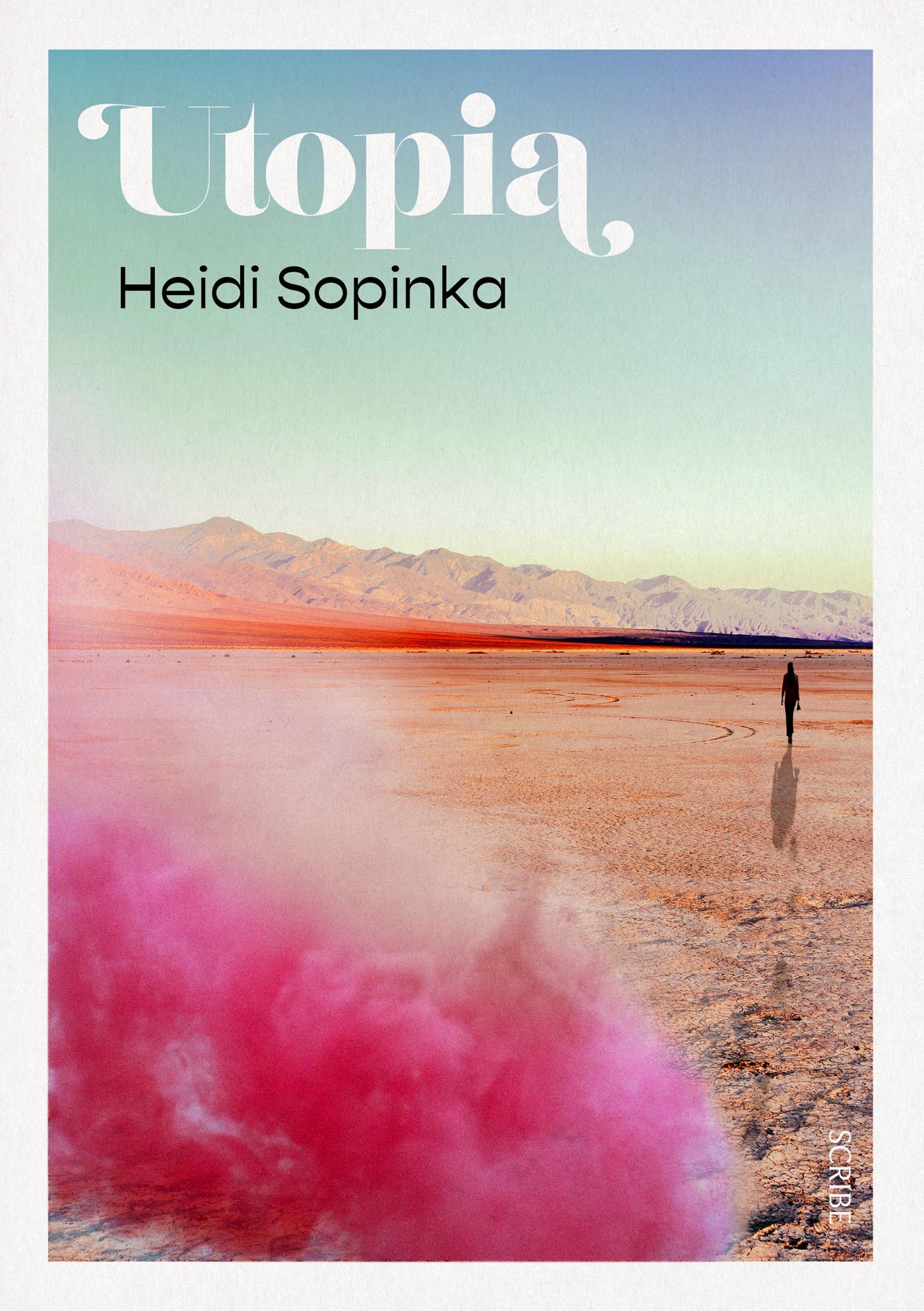

Utopia by Heidi Sopinka is published by Scribe and is out now.