I don’t remember “discovering” Jagged Little Pill by Alanis Morissette. It felt like something that had always been there, like water, or Ant and Dec – a part of the fabric of everyday life. Always booming around the house and the back of the car; one of the only albums in my parents’ arsenal that I didn’t try to drown out with pre-teen angst, shitty headphones and a burnt copy of NOFX’s Punk In Drublic (the height of musical achievement, to me, in 2001).

However, I do remember Jagged Little Pill ‘hitting’ around the age of 13, when it became the album of the summer for me and my girlfriends. We played it relentlessly at house parties, in parks, and on camping trips. We screamed it on the backs of buses and shoehorned personal jokes into the lyrics – partly a way of claiming Morissette’s unbridled sexuality and anger as our own, but mainly to be silly little pricks. At the time it was one of few cultural artefacts my friends and I could enjoy in the privacy of teenage girlhood; something we didn’t have to share with anyone else or justify our relationship to. It was certainly an outlier among the 2000s pop-punk and emo albums we were mostly banging at the time, which were steeped in a culture of male frustration, songs about despicable ex-girlfriends and “oh you like Green Day do you? What’s track six on their second album then?” A fun era, but one that constantly relegated young women to the sidelines. Jagged Little Pill was the first album I remember hearing that turned the feminine experience inside out. It said what it wasn’t supposed to in a way that – between all the threats of violence and harmonica solos – should have been inaccessible, but felt irresistible.

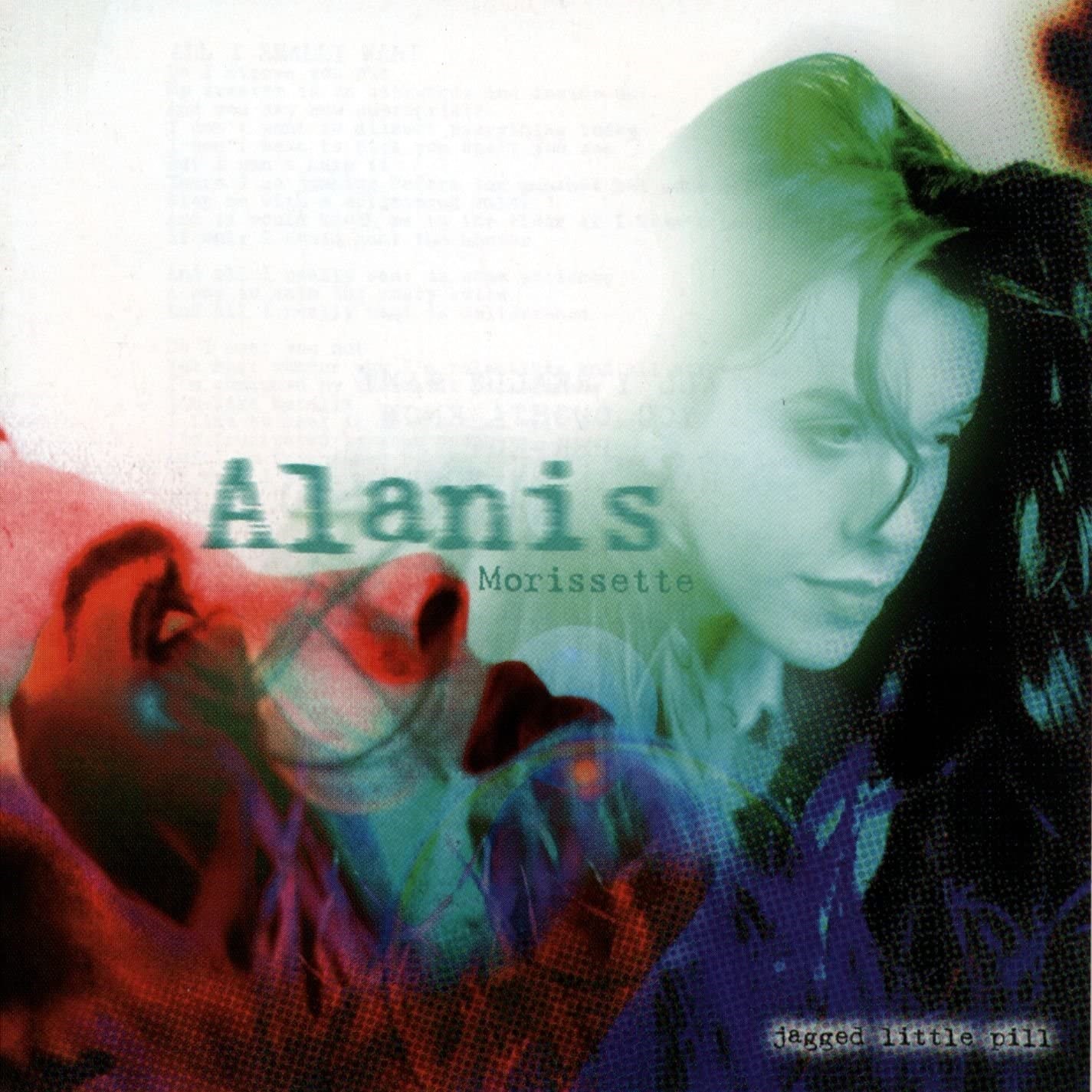

With her anti-objectification anthems and mane of natural brown hair, Alanis Morissette is a Gen X idol in almost every respect. She didn’t reflect the 00s pop factory that I grew up in, and she was glaringly absent from the 80s deluge of dicks-in-spandex that defined my mam’s twenties. And even though we came to it at different ages – me in my pre-teens, my mam in her early thirties – we both consider Jagged Little Pill a formative staple. So when the 25th-anniversary tour finally came to the UK last week after a two-year delay, we went together to see how the album resonates several decades on.

At the second of two dates at London’s O2 Arena, the crowd is notably diverse. There are mothers and daughters, husbands and wives, groups of young girls and gay guys and blokes with their mates; everyone queuing up for pints and T-shirts emblazoned with the lyrics “You know how us Catholic girls can be” in college font. In the seats behind us, two Italian women trade stories of all the times they’ve seen Morissette perform. I ask my mam what she thinks it is about Jagged Little Pill that attracts such a mixed audience. “It’s that angst and frustration,” she suggests. “It’s not just women that are understanding of that, it’s anyone going through something or struggling with their identity. But I do think the timing is right for this album now, because women are going through so much of this stuff again.”

“Morissette found herself singing – often beautifully, often like a sick animal – about exploitation, control, revenge and sucking someone off in the cinema” – Emma Garland

First released in 1995, Jagged Little Pill was a groundbreaking feat of female nerve. The charts at the time were flooded with the male-dominated genres of grunge, hip-hop and Britpop, while women were represented mostly by solo vocalists like Mariah Carey, Celine Dion and Whitney Houston. Third-wave feminism was proliferating through the underground worlds of riot grrrl and indie rock, but my mam tells me that was something you had to seek out. By contrast, Morissette was signed to a major label that was priming her for a career of dance-pop and piano balladry in the vein of Debbie Gibson or Tiffany. Jagged Little Pill, then, was a rejection of mainstream conventions that was impossible to ignore because it was being played on rotation between Bon Jovi and Bryan Adams. Far from the starlet she was expected to become, Morissette found herself singing – often beautifully, often like a sick animal – about exploitation, control, revenge and sucking someone off in the cinema. Things we now speak about publicly were buried within her sarcastic lyrics and blistering choruses. The call was coming from inside the house, and while the references to power-hungry industry executives and sexual abuse went over a lot of heads at the time, millions of people felt the mighty voice behind them.

The show opens with a montage of Morissette’s career highlights around the release of Jagged Little Pill. The lights go dark and there’s a rapid sequence of magazine covers, broadcast news segments, SNL sketches, a clip of her fighting Jewel on Celebrity Deathmatch, a few scenes from her cameo in Dogma, and an interview in which she’s asked where a 21-year-old even goes after spending 11 weeks at number one, having the best-selling album of 1996, and literally playing God. In response, she smiles and laughs. On stage, guitars ring at the start of All I Really Want and her voice – as fierce as it’s ever been – belts out the casually confrontational opening lyric: “Do I stress you out? / My sweater is on backwards and inside out.”

“We screamed it on the backs of buses and shoehorned personal jokes into the lyrics – partly a way of claiming Morissette’s unbridled sexuality and anger as our own, but mainly to be silly little pricks” – Emma Garland

From there, Morissette and her band play the album in full, with brief instrumental segues of songs from later releases. When the setlist reaches Ironic, the screen rolls footage of Taylor Hawkins – the late drummer who, before joining Dave Grohl in Foo Fighters, served as Morissette’s drummer on the Jagged Little Pill tours and appears in several of her music videos. It’s an emotional tribute, and a reminder of just how steeped in rock and roll history the album is despite its pop sensibilities (the credits also feature Red Hot Chili Peppers members Dave Navarro and Flea, Simply Red’s Gota Yashiki, and legendary studio drummer Matt Laug).

It’s hard to grasp the scale of the cultural impact Jagged Little Pill had at the time – especially considering Morissette keeps a relatively low profile these days. It takes a special kind of songwriting to hook, line and sinker everyone from an 11-year-old Avril Lavigne to a twenty-something Kevin Smith to the board of the Grammys, where it swept five out of nine awards. Jagged Little Pill was the best-selling album of 1996 and, at 21, Morissette became the youngest artist in history to be certified diamond platinum (a record beaten by Britney Spears with … Baby One More Time in 1999) and win Album of the Year (beaten by Taylor Swift’s Fearless in 2010). It was a truly cross-cultural behemoth, which partly explains why my mam didn’t come to it the way I came to discover similarly subversive albums by the likes of Hole and Bikini Kill – by digging through music blogs and Limewire in the solitary glow of a computer. Instead, Jagged Little Pill was recommended to her by her male friends. “I think they could see that it was my kind of thing – this woman up there being confident in herself and speaking freely,” she remembers. “I think, especially when you’re in male company, you don’t always show your true self. But it’s interesting that they saw that strength of character in me and thought that I could relate to her and her style of music.”

In 1995, I would have been around six years old. With the tunnel-vision of first-time parenthood in full effect, my mam explains the impact Jagged Little Pill had on her at the time. “When you make that transition from being a single woman with no responsibilities to having this overwhelming love and responsibility for this child, and you’re focussed on trying to do your best, you kind of forget who you are along the way,” she says. “Listening to Jagged Little Pill was like rediscovering who I was, and remembering that I was still an individual, not just a mother or a partner.”

Morissette’s mark on today’s music landscape is inescapable, particularly for women. She’s credited with kicking open the door for pop-rock artists like Pink and Kelly Clarkson in the 00s, and her influence continues to reverberate across all stratas of guitar music. It’s in the colossal intimacy of songwriters like Phoebe Bridgers and Olivia Rodrigo, and the boundary-pushing performances of pop stars like Halsey, Billie Eilish and Tierra Whack. In 2014, Jagged Little Pill even re-entered the charts after featuring heavily on Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon’s The Trip to Italy – a reminder that it wasn’t just female rage that made the album connect with people, but songwriting so undeniable it has middle-aged men on their holidays ugly-screaming “Does she speak eloquently? And would she have your baby? I'm sure she’d make a really excellent mother!”

“Musically, it was really what we needed to hear at that time, because everything in pop was so saccharine,” my mam says of how it disrupted the charts in the 90s. “You went from totally male-dominated cock rock to totally male-dominated grunge. To my mind, Alanis Morissette was the first woman to break the stereotype of women in music at a mainstream level. She came on stage in a baseball shirt, a pair of Converse – hair all over the place – and just kicked arse.”

That image proves to be just as powerful in 2022 as it was in 1995, with teenage girls and older couples alike whooping and cheering as Morissette whips her hair across the stage like James Hetfield in a tumble drier. For my mam, it was the best Morissette show on record. For me as a first-timer, screaming “Every time I scratch my nails down someone else’s back, I hope you feel it” alongside a stadium full of people gave me the same give-no-fucks feeling as singing it with my best friends in a tent in 2003. It’s one of those albums that rearranges your insides for life, which – as much as I still rate it – is more than I can say for Punk In Drublic.