Ione Gamble’s laugh is contagious. Whether she’s giggling at something said on an episode of her popular weekly Polyester Podcast, or through Zoom, as I mention to her that I loved her use of the word “toads” (twice, if I remember correctly), in her debut book Poor Little Sick Girls. Gamble grew up alongside the internet, navigating contemporary feminism, the wellness industry, social media and the rise of hustle culture as any young millennial woman did. But unlike most, she did so while learning to live with Crohn’s disease, the chronic illness she was diagnosed with in her late teens.

While her peers were diving headfirst into life as free, independent adults, Gamble was spending most of her time in hospital wards. Much of the rest of it was spent bedbound, juggling her health with the plans she’d made for herself when she was well. Despite her diagnosis, Gamble attempted to work her ‘dream’ magazine job after university, but with a body failing to comply and an office environment not willing to accommodate her illness, she quit and decided instead to focus on her feminist intersectional art and culture zine, Polyester.

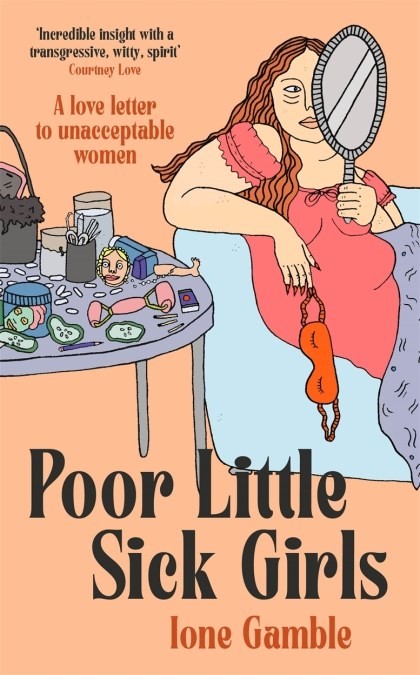

A decade on, Polyester’s success, much of which was forged from Gamble’s bed, can be seen carved in pink on the cover of Poor Little Sick Girls, the collection of essays she writes about health, feminism, the internet and class. There, you’ll see the artwork she fought for (authors don’t usually get much of a say over their covers, especially debut ones) and a pull quote from one of Gamble’s idols, Courtney Love (“incredible insight with a transgressive, witty spirit”). Inside, Gamble perfectly articulates the particular cultural moment we find ourselves in, both online and off, highlighting how our obsession with wellness, work and individual identity politics looks to – and impacts – marginalised people. Not only does she untangle how we ended up with a fourth wave of feminism so co-opted and influencer-fronted that millions are choosing to dissociate entirely, but she provides hope for a future that looks vastly different (even if it’s still painted millennial pink).

Tavi Gevinson, the founder of the groundbreaking online teen magazine Rookie and a woman who inspired a young Gamble to start Polyester, dubbed Poor Little Sick Girls “thrilling.” But it’s Gamble’s own words that capture the essence of her book the most: “Society has no script on how to deal with a fat, chronically ill woman in her twenties who refuses to accept invisibility. Because of that, the potential to write my own narrative is infinite.”

Isabelle Truman: There are constant critiques of the wellness industry, but your perspective – as someone who can’t do a five-day juice cleanse to result in a feeling of optimal health, and who has to practice self-care in the most boring and unintentional ways – is one that’s often completely disregarded in these conversations. The way you defined the difference between health and wellness in the book feels really important here.

Ione Gamble: Wellness is a lifestyle pursuit, but one that’s so tied to our health. Peak wellness is basically symbolising to the world that you have everything together – you’re in a good place in your career, you have great relationships – and it all starts with you and your body. The thing is, it’s a totally faulty idea that relies on us buying into things, whether it’s on a moral level – buying into the fact that fat people are bad or unwell people are scary – or whether it’s physically buying into things, like juice cleanses or athleisure or the right food. It’s so entwined with everything we do, even alcohol now. There are protein shake cocktails. [Everything] has to have the purpose of making us better, whether that’s better in body or mind or, ideally, both. Not only does it not allow for real joy, or doing something for the sake of it, but it completely disregards disabled and chronically ill people as being useless to society. You’re not useful unless you’re a healthy person, you’re not worthy of respect unless you take care of yourself. It’s really dangerous, especially after what we've been through with the pandemic. To see it become more pervasive, rather than less, is quite terrifying.

IT: Another thing that seems to have heightened in recent years is the rise of individualism, which is a topic you recurringly touch on throughout Poor Little Sick Girls.

IG: We’ve had such a fierce focus on individualism in recent years, both politically and non-politically. When it comes to social media activism and celebrity, especially, it feels in such juxtaposition to Tumblr and my upbringing on the internet. Even if you had your own individual profile, Tumblr was very collective-based: I followed art collectives and feminist collectives and met so many like-minded people. Everything is much more skewed to being an individual now, especially online. It’s disheartening because working collectively is not only more effective but it’s more fulfilling.

“Everything is much more skewed to being an individual now, especially online. It’s disheartening because working collectively is not only more effective but it’s more fulfilling” – Ione Gamble

IT: When you were linking individualism to the likes of dissociative feminism, you wrote a sentence I really loved: “Cynicism is a far easier road to follow than true vulnerability.”

IG: We’ve had this earnest kind of feminism in its worst form over the past decade. Girlboss feminism and infographic feminism and ‘dump him’ feminism. That was very earnest in an embarrassing way. It’s just cringe to look at, it gives me the shivers. But then cynicism, when it comes to the internet, is so often just dissociative feminism. We’re more drawn to giving attention to people that exist on either end of the spectrum. I hope people try to find a bit more balance online in the way they react to things and the way they post things because I think in that space, more exciting things can happen than constantly either trying to be a fierce cynic or this weird, self-love girl boss.

IT: One of my favourite essays was where you wrote about “good” and “bad” taste and how it intersects with class. You wrote that taste can be another way for rich people to assert their dominance over the working class. Can you talk about this a bit?

IG: As I say in the book, before I worked in these industries, I thought there were just lots of different people with lots of different interests who found each other and came together to make magazines or fashion brands. And then I found out, it’s actually the same ten people all the time that do everything and they’re all actually descended from the aristocracy. We think we have all of this freedom – the freedom to be ourselves and the freedom to like the things we like – when really, we exist under so many layers of class disparity that always puts working-class people behind. Even if you don’t want to work at a magazine, or be in the creative industries, even if you’re just a consumer of these products, they have an influence on you in a way that doesn’t seem overt. Maybe it’ll make you feel bad about the rug you want in your home or the picture you want, or the television you like. It’s constantly asserting the position that rich people have better taste and know what’s good for them and poor people don’t and therefore they will consistently make bad decisions about their own lives. It’s really fucked up that we live in a culture that keeps allowing that to happen, even though we have all of this kind of false diversity and false inclusivity. Really, that hasn’t changed the make-up of anyone in any industry. I saw a stat the other day that said our generation of journalists is more upper-middle-class than our parents. Like, how has it got worse?

IT: You also mention something I’ve noticed a lot since living in the UK especially, which is rich people trying to assert their hardships as a way to seem less privileged and more relatable.

IG: Rich people have cottoned on to the fact that they might be considered inauthentic. But I feel like it’s more authentic to actually be open about being disgustingly rich. In Bling Empire Season Two, which has just come out, they are so overt about their wealth. It’s entertainment, and rich people should be entertaining, because what other purpose do they serve?

IT: I loved your essay about rage. In in, you wrote: “Women and marginalised people not only do not have the representation they deserve, but the absence of a mirror held up by the world has real implications for our emotions and what we feel we can do with them. We have no framework for where our rage can go, what it can do or the implications of unleashing it.” What has your process been like in terms of feeling and processing rage?

IG: Really difficult. Because, especially as women and marginalised people, we’re taught that rage is inherently unnatural. If you’re feeling it, there’s something wrong with you, as opposed to there being something wrong with the world, or the circumstances that have put you in that position. We’re constantly being told to rationalise our rage. If you’re angry, you almost have to intellectualise that anger in a way to make it valid, when, really, it’s just a product of the era we’re living in right now. I mean, there are so many intellectual and unintellectual reasons to be angry at the world. On a personal level, as someone who probably gets angry quite a lot, it’s accepting that. Obviously, not outwardly taking it out on other people, but accepting there are tangible reasons to be angry and it’s not a personality flaw to feel rage, if that makes sense.

“I feel like it’s more authentic to actually be open about being disgustingly rich ... rich people should be entertaining, because what other purpose do they serve?”

IT: Despite the many downsides of the internet, I get the sense you still feel hopeful about it.

IG: If you take when I first went on the internet, which was like 14 or 15 years ago now, and look at how much has changed in that time, or even how much has changed since we were 18 to now, there have been so many different phases: some incredible and some really terrifying. The next ten years could go either way, but I do think it has such great potential. For example, the internet is kind of the only open resource we have. If we don’t keep closing those doors, it can be such an amazing way to share information and genuinely educate people. It’s like anything else: who gets precedence on these platforms and who we give the power to is really key. Right now, I think we’re at quite a miserable stage of the internet – and also such a weird stage because I have no idea what Web 3 is or what the Metaverse is going to be and I have no interest in it. But I do still think there is radical potential to be had through the internet as a tool for communities, definitely.

IT: It feels almost embarrassing today to say you’re a feminist, which is so vintage – I remember thinking it was crazy our parents’ generation didn't identify with the word. This is a big question, but where do you think the movement goes from here?

IG: Even though I know a lot of people shit on TikTok feminist niches – dissociative feminist ones and bimboism and all of these things – I actually do think it’s a good thing that it’s splintering off into all of these different subsections. Because when you have things painted with such a broad brush, the way we’ve had feminism for the last four years with the like H&M T-shirts and Netflix shows, that obviously doesn’t work because it’s so watered down. I think if people are organised within their own niches, there is potential. In the book, I write about how feminism has become, more than ever, a cultural movement, rather than a political one. And the thing is, we need both more than ever. I really believe you have to just stick with the label, even when it’s embarrassing, and just prove it can be something better than what it is in that moment. And I hope that’s what happens.

Poor Little Sick Girls is out now on Dialogue Books