Ahead of this year’s Cannes Film Festival, we recommend five films by Lee Chang-dong – a director who helped put Korean cinema on a global stage

Korea is gearing up for another big year at Cannes this month, as Park Chan-wook’s Decision to Leave competes for the top prize alongside Hirokazu Kore-eda’s first Korean film, Broker. The star of the latter is Song Kang-ho, whose performance in Parasite helped launch Bong Joon-ho’s Palme d’Or winner into the global cultural zeitgeist – where it has remained ever since.

So successful was Parasite, though, that it often overshadows the achievements of other Korean filmmakers who effectively laid down the path for Bong’s success. One of the most prominent of these is undoubtedly Lee Chang-dong, director of Burning and countless other masterworks, whose Palme d’Or and Oscar nominations in 2018 and 2019 offered a preface to Parasite’s breakthrough the following year.

Lee, an elite screenwriter, director and producer, is himself no stranger to Cannes – four of his six features have appeared in competition at the festival across his career. Famed for his acute presentation, themes of tragedy and psychological trauma, and intricately woven narratives – which often focus on the deeply complex characters from the corners of society (Argentinian writer Eduardo Antin sums up his films as a “social X-ray of Korea”, while actor Steven Yeun describes how he “captures the human condition in all of its forms, whether it’s ugly or beautiful”) – he also boasts an uncanny knack for casting breakout talents in pivotal roles. His awards include the Silver Lion at Venice, the Fipresci Prize at Cannes, and three Best Film prizes from Korea’s Grand Bell Awards; three of his works have also been selected by his home nation as official submissions to the Oscars.

At Jeonju International Film Festival this month, Lee’s latest short film, Heartbeat, received its world premiere alongside a new documentary on the director’s work, titled The Truth of the Invisible. With a full retrospective series of Lee’s films also screening at the renowned festival, AnOther took a closer look at the career of Korea’s most novelistic filmmaker; and one of its greatest contemporary auteurs.

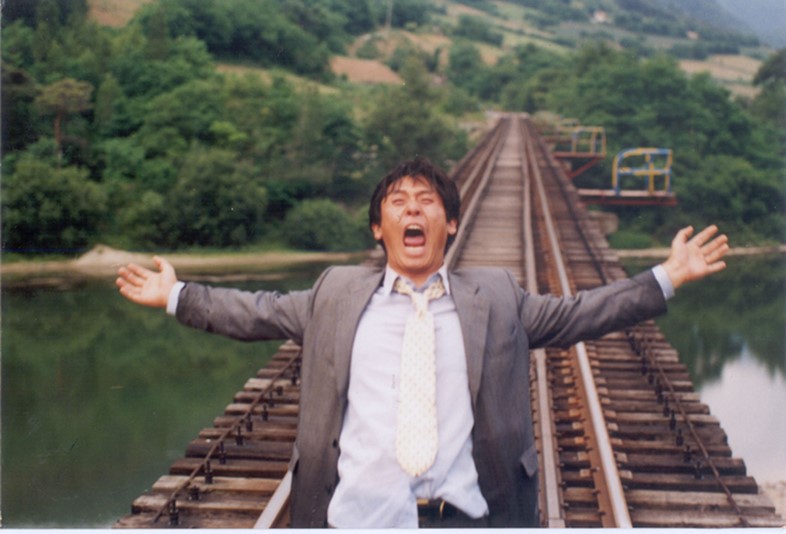

Peppermint Candy (1999)

In the opening chapter of Lee’s second film, a despairing Kim Yong-ho (Sol Kyung-gu) throws himself in front of a moving train in an act of suicide. In a narrative told in reverse chronology thereafter, the film unravels the mystery of why in a series of seven chapters, leading towards the reveal of a great trauma that occurred 20 years prior. All the while, a haunting omen recurs in the periphery: the ominous presence of the train and its tracks loom in every segment of the story, constantly reminding the viewer of the terrible fate that awaits its troubled protagonist.

In a Q&A at Jeonju International Film Festival in May 2022, Lee name-checks Wong Kar-wai and Quentin Tarantino as fellow filmmakers who experimented with time in narrative storytelling in the lead-up to the turn of the century (Christopher Nolan’s Memento, released a year after Peppermint Candy, is an even more apt comparison). But the theme was particularly poignant for Korea, a country which evolved from a developing country and military dictatorship into a democracy and economic power in the 20 years examined in Peppermint Candy. The growing pains of the nation are referenced implicitly and explicitly throughout the film, with images and themes mirroring events such as the 1980 Gwangju massacre and resulting student uprisings.

With such historic and narrative depth on show – capitalised upon by an astonishing, tour-de-force performance by actor Sol Kyung-gu, who won prizes at the Grand Bell and Blue Dragon awards for his work – Lee arrived on the world stage in breathtaking fashion, competing for the CICAE Award at Cannes. The film remains a landmark feature in New Korean Cinema, and one of the country’s greatest film productions.

Oasis (2002)

At the centre of a cold, grey Korean metropolis, a man exits the bus to ponce a cigarette from a stranger. He hunches and fidgets, and the camera twitches as it follows him. This is Hong Jong-du (played by the magnetic Sol Kyung-gu); a loveable oddball who suffers from a mild mental disorder, and who has just been released from prison for involuntary manslaughter. As he attempts to reintegrate, he meets a beautiful woman, Gong-ju (Moon So-ri), who is stricken with cerebral palsy. She’s the daughter of the man he accidentally killed in a car accident – and their would-be romance has no place in the world in the eyes of their families.

Oasis is a beautiful tale of love and loneliness told through the eyes of two misfits who have been rejected by society. With two outstanding performances carrying the film (the same two leads of Peppermint Candy) and Lee’s compassionate, intimate filmmaking spiked with liberal use of comedy, this heartfelt drama is captivating from start to finish.

At Venice Film Festival, Oasis was nominated for the top prize: the Golden Lion. It didn’t win, but it did take home four other awards – including the Silver Lion for Best Direction, and the Marcello Mastroianni Award for Emerging Actress for Moon So-ri – making it only the second Korean film to win a prize at the festival, and the first since 1985.

Secret Sunshine (2007)

In Lee’s fourth film – his first to feature a female protagonist – a young mother named Lee Shin-ae (Jeon Do-yeon, The Housemaid) moves with her only child to the rural town of Miryang following the unexpected death of her husband. But shortly after she arrives, Shin-ae is beset by an even greater tragedy that leaves her in a state of utter devastation.

A local pharmacist invites Shin-ae to join a local religious community, with the promise that allowing God into her life will enable her to see light and happiness in the world, but this path, too, is plagued with difficulty. All the while, a kind-hearted mechanic (Song Kang-ho, Parasite) has taken a quiet affection for Lee, and becomes a kind of guardian angel as she endures unimaginable grief.

Once again, the intricacy and depth of Lee’s novelistic writing ensures that Secret Sunshine is as powerful a story as any of his other works. No shot is wasted in this tale of loss and faith, with motifs such as blue skies and rays of light filling each shot with meaning and thoughtful ambiguity. In the end, it is another sensational acting performance that makes the film all the more impactful to witness, and Jeon Do-yeon was deservedly awarded the Prix d'interprétation féminine at Cannes, while the film itself competed for the festival’s top prize.

Poetry (2011)

Poetry is the quiet, ruminative story of Mi-ja (played by Yoon Jeong-hee, in her first role in 16 years) – a woman living on the outskirts of a countryside town, who discovers she has Alzheimer’s shortly before enrolling in a poetry class. At the same time, Mi-ja is shaken to learn that a schoolgirl has recently committed suicide by jumping from a bridge; in her diary, the schoolgirl named Mi-ja’s own grandson as one of six classmates who had repeatedly raped her in the science lab.

A plot like this could easily slip into melodrama, but Lee’s film instead offers a ruminative character study delivered with poise and nuance, and filmed with bright, natural light that captures a wealth of unspoiled rural scenery. The latter serves as a poignant backdrop as Mi-ja yearns for a spiritual awakening in the twilight of her life. Despite finding herself frustrated as she searches for inspiration, the answer lies right in front of her: “poetry can be found even in the dishwashing basin,” her teacher tells the class.

Lee’s fifth feature film was the recipient of the Best Screenplay Award at Cannes in 2010, and four awards including the Best Film and Best Actress prizes at the prestigious Grand Bell Awards in Korea. The Guardian’s lead film critic Peter Bradshaw would later liken the film to the restrained work of Japanese icon Yasujirō Ozu; he later placed it in a list of Korea’s best modern films in 2020 – ranking it fourth behind only Oldboy, Parasite and The Handmaiden.

Burning (2018)

Eight years passed between Poetry and the release of Lee’s most recent feature – but the wait was worth it. Burning effectively forecasted the success of Parasite a year later, after it competed for the Palme d’Or at Cannes and made the final nine-film shortlist for the Best International Feature Film prize at the Oscars – and it remains Lee’s most internationally revered work thanks to widespread distribution and huge critical acclaim.

Like Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s 2022 Oscar-winner Drive My Car, Burning adapts a Haruki Murakami short story and expands it into something even greater. The film opens with a young man named Jong-su (Yoo Ah-in, of Netflix’s Hellbound) who encounters a beautiful and mysterious young woman, Hae-mi (Jeon Jong-seo), who claims to know him from the town they both grew up in. After a mutual attraction leads to infatuation, she disappears on a trip, only to return with a rich new friend in tow, Ben (The Walking Dead and Minari’s Steven Yeun). The trio form a tentative friendship, but Jong-su finds himself increasingly uncomfortable. And when Hae-mi disappears without a trace once again, and as Ben reveals a curious hobby for burning down greenhouses, Jong-su becomes tormented by an overwhelming sense of paranoia.

By now, of course, the brilliant acting performances are expected – and Yoo, Jeon and Yeun are all outstanding in their corners of Burning’s twisted love triangle. Other members of the crew shine as well; master cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo (Parasite, The Wailing) excels, particularly in capturing the film’s most Lynchian moment – when Hae-mi dances half-naked at dusk to the sound of Miles Davis’ hypnotic jazz number Générique, a pivotal moment of the film. Elsewhere, the desolate and eerie score penned by Mowg (I Saw The Devil) conjures up an atmosphere that guides the film’s subtle shift from mystery into psychological horror.