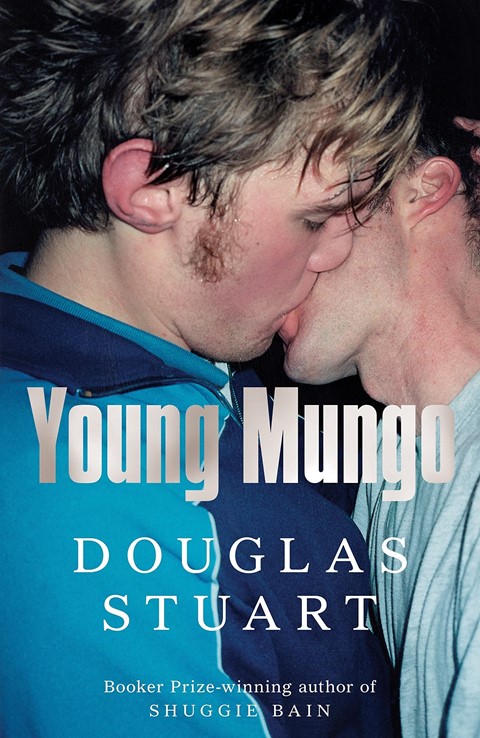

As his second novel is released, the author talks about the changing face of masculinity, gang culture in 1990s Glasgow, and the value of queer visibility in art

Douglas Stuart’s writing isn’t just vivid and riveting; it’s also heart-wrenchingly tender. The Glasgow-born author – a former designer for Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren – won the Booker Prize in 2020 for his remarkable debut novel Shuggie Bain, a poignant modern classic. Written in throbbingly vital prose, it tells the story of a young boy whose childhood is defined by inner-city poverty, his mother’s alcoholism and his own effeminacy, which is deemed “no right” by tough Glasgow locals.

Out today, his stunning follow-up novel Young Mungo is even more enthralling and in places, equally bleak. Like Shuggie, Mungo is a gentle and sensitive young man whose fundamental goodness is being battered from all corners: his brother Hamish is a violent gang leader, his mother is a selfish yet resilient alcoholic, and his smart sister Jodie is perhaps too focused on dragging herself up in the world to fully understand him. The book begins with a fishing trip intended to make a man out of him, but it quickly descends into abject terror.

For Mungo, a ray of hope arrives in the form of James, a self-possessed local boy who has turned a nearby pigeon doocot – or dovecote – into his own quiet sanctuary. But because they live in working-class Glasgow in the early 1990s, their blossoming romance feels impossible even before you factor in one boy being a Protestant and the other a Catholic.

As Stuart says here, it’s a story rooted in truth and designed to inspire compassion and empathy – something Young Mungo more than comfortably achieves.

Nick Levine: Where did the germ of the idea for Young Mungo come from?

Douglas Stuart: I came of age in the very early 90s. We were living under Section 28, it was a time of fear because of the Aids crisis, and masculinity was very narrow. There was no queer visibility in my youth – the first Gay Pride march in Scotland didn't take place until 1995 – so as a teenager I was doing everything I could to conceal my queerness. And at the same time, because I was part of such a tight knit community, I had to try and fit in with the lads around me. In a funny way, I became my own oppressor; I felt like I had to be performing masculinity.

So when I was sitting down to write Young Mungo, I was thinking about performative masculinity and how young lads can get caught up in these gangs. We can egg each other on to be rougher and tougher and more sexualised with girls. I also had a longing to write a love story about two young men who fall in love with each other, which is taboo in a lot of communities, and certainly was at that time. And for these two young men, it's also taboo because it involves crossing some kind of gang divide.

NL: We talk a lot now about toxic masculinity, but the codes of masculinity imposed on the characters in Young Mungo feel like something quite different from that.

DS: I think it’s [a] more suffocating masculinity. I don’t think masculinity is naturally toxic and I think we overuse that phrase. I think masculinity is a great thing, it’s part of society, and I think we’re all complicit in how it shows up. I tried to write a very broad spectrum of men in this book; we have very hard men like Hamish – he’s very violent and his reputation as the gang leader controls everything he does. But we also have the gentleness of [Mungo’s neighbour] Chickie and the gentleness of James, who’s a very upstanding, decent man. What I was trying to write about is more the idea of conforming within masculinity. Mungo is a character who doesn’t have parents; he’s essentially a motherless son. All the people around him are trying to get him to ‘man up’ through lots of different ways. The pressure on this boy grows all the way through this book until at the very end, he emerges as a man. It’s just not the man that anyone around him had expected.

“I understood loss and grief and I understood what it meant to be gay and to have the shit kicked out of you for it. I think that’s important for the authenticity of the work” – Douglas Stuart

NL: Mungo’s neighbour Chickie is such a fascinating character. Because he’s clearly gay, he’s looked upon with pity and contempt by his neighbours, but I found something courageous in the way he navigates his life in the face of so much homophobia. What made you want to include this kind of queer character?

DS: I think he’s really courageous, too. He wasn’t in the book when I sat down to plot it, but he kind of showed up at the side of the page and said: ‘I have something to tell you.’ I was thinking about how so much of our queer canon comes from a place of middle-class life and privilege. There are a lot of boarding schools, a lot of private clubs, a lot of sexual exile to large liberal cities. That’s been the narrative for queer men for hundreds of years: we run away to New York or London to find our tribe and find ourselves. And so I was thinking about queer working-class stories and how they’re often erased. There were always a couple of men on the scheme [estate] that I grew up in who would be referred to as ‘the bachelor’. Maybe they would have looked after a mother, or maybe they lived by themselves. But to me as a young queer man with some kind of gaydar, I always knew they had quite a feminine spirit. So I was really thinking about the loneliness and isolation that they went through and how they’re the backbone of so many queer communities. We look to our elders to guide us and show us how to be ourselves as gay people. Chickie performs that role for Mungo; he’s a real saviour in the book.

NL: Do you find it frustrating when people – journalists, I suppose – try to decipher the precise extent to which Shuggie Bain and now Young Mungo are semi-autobiographical?

DS: It’s never annoying, I just don’t want people to get the wrong impression from it. I felt it was important for me to share my own background when I was writing these books because I wanted people to know that I was writing about the world that I came from. Even if the events [in the books] hadn’t actually happened to me, I wanted them to know I understood gang culture in Glasgow because I’d run with it. I understood loss and grief and I understood what it meant to be gay and to have the shit kicked out of you for it. I think that’s important for the authenticity of the work. So I don’t get frustrated, but I think oftentimes when people talk to me, they jump quickly from my work to just wanting to talk about me and my life. That can be a little difficult, because I’d rather talk about my craft.

“I don’t think masculinity is naturally toxic and I think we overuse that phrase. I think masculinity is a great thing, it’s part of society” – Douglas Stuart

NL: With that in mind, what do you hope people take away from Young Mungo?

DS: I hope they come away with the love story, and I hope they feel bereft when the characters leave them. I write, I think, to engage my readers in some kind of concern for my characters. Like, when they left Shuggie on the brink of his manhood, I wanted them to wonder about what happens to kids that are born into addiction and poverty, who are born so far behind the starting line in life. And I think with Mungo, I want the same thing. Is he going to run away with James? Are they going to be OK? What does the future hold? I’m all about asking people to reflect on how it was for people [back then], not how it might be for them today.

Young Mungo by Douglas Stuart is out now via Picador.