Few bands capture the soulful, freewheeling spirit of the 1990s quite like Primal Scream. The Scottish rock group burst to the fore at the start of the decade with their 1991 album, Screamadelica – a euphoric, 11-track trip through the UK’s then-burgeoning acid house scene. With its fluid approach to genre and its joyous, transcendental production, the record went on to spark its own kind of psychedelic revolution, radically reshaping the way we create and consume British pop music.

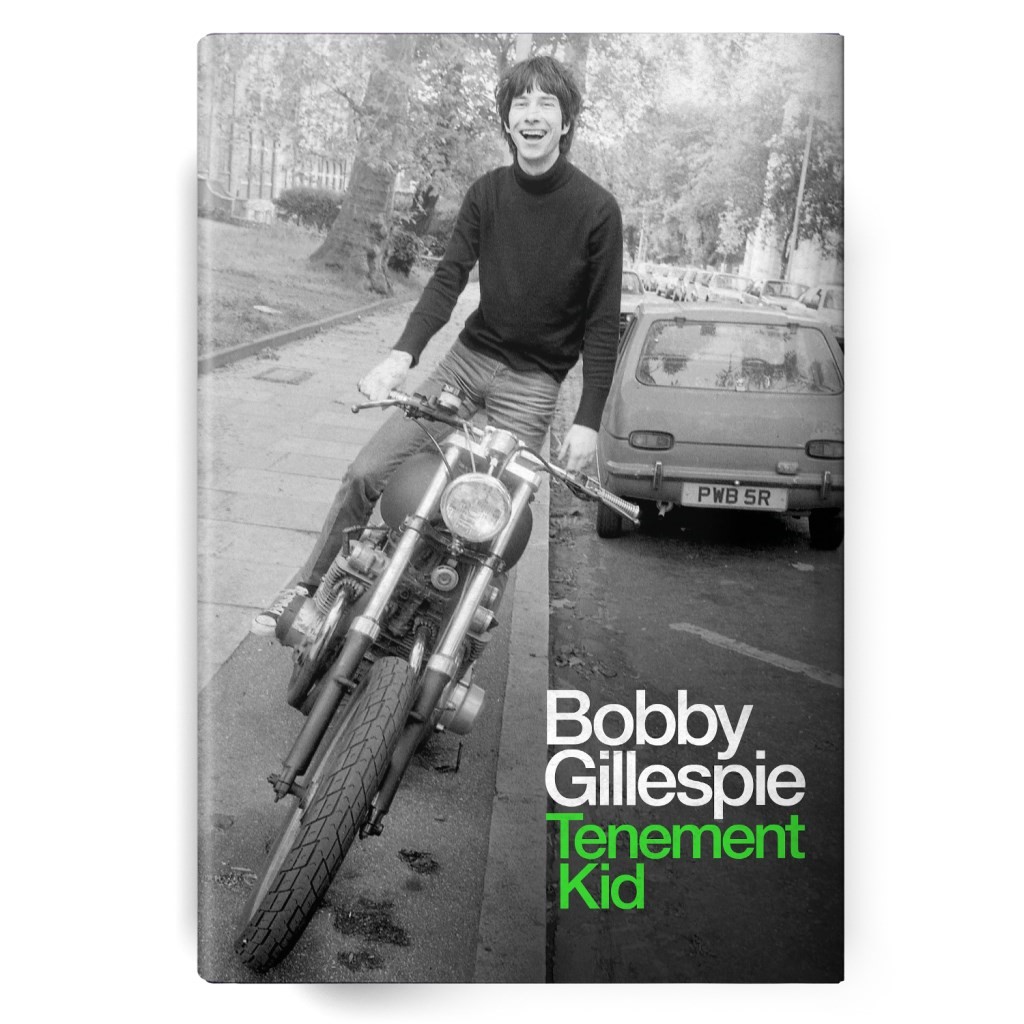

So when Bobby Gillespie, Primal Scream’s frontman, announces a memoir documenting this pivotal moment in UK culture – our second “Summer of Love” – you know it’s going to be special. The book, titled Tenement Kid, is a rapturous account of the acid house movement, as well as Gillespie’s early life; beginning with his childhood on the streets of Springburn, Glasgow, to his gradual immersion into the world of rock and roll. Published 30 years after the release of Screamadelica, Tenement Kid is an impassioned ode to music, love, nostalgia, rebellion and class consciousness – blazing “a righteous path through a decade lost to Thatcherism and saved by acid house.”

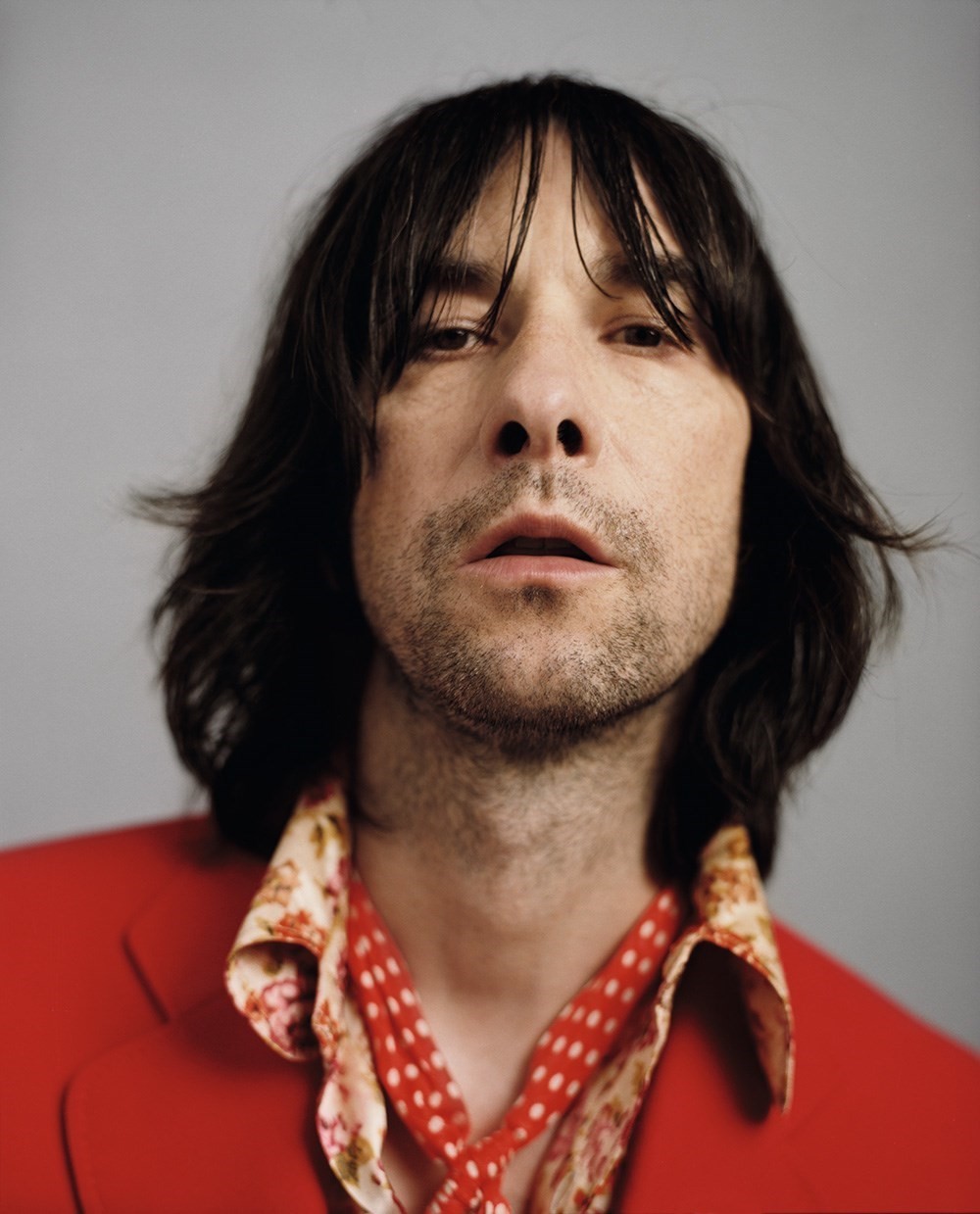

Here, in a candid conversation with Jefferson Hack, Gillespie talks more about the book’s inspirations, his memories of the era, and why his love for dance music will never die.

Jefferson Hack: It’s an amazing book, Bob. Congratulations. I got such a euphoric recall reading it, especially the last few pages when you get into the 90s and start mentioning all the club nights and describing all the parties – some of which I went to.

Bobby Gillespie: That’s good. I was just trying to relay to people that might not have been around then – who were too young or not born yet – the excitement of those days and how important they were. Screamadelica is maybe our most valued LP, and I just wanted to describe how important acid house was to the making of that record.

JH: The book is full of love: for rock and roll, for your family, for your bandmates ... The passion is really infectious. How was the experience of writing it?

BG: There are a lot of different emotions obviously, but I’d say that overall the feeling was one of self-realisation. I became aware that I had pretty good powers of description, and that I could evoke time and place using emotional memory, my writerly abilities, and my imagination. So it was a really self-empowering experience, because I’m a way more confident person now than I was last year when I was deep into the writing process. I feel that I’ve achieved something creatively. Not in an egocentric way, but more like there’s something I’ve now proved to myself, that I can take on a creative endeavour.

JH: What was the experience like emotionally? Was it cathartic, therapeutic, nostalgic?

BG: It was all of those things. It went from elation and joy to pain. But in writing about pain you exorcise yourself; you free yourself from the shame, guilt and sorrow that you may have experienced at the time – whether that’s being thrown out of a band that I really loved being a member of, or whether it’s sadness about the state of my parent’s marriage. It’s definitely a cathartic experience to write about these situations and also come to terms with them.

I also had to be very careful about the way I handled situations in the book that were describing emotional upset. My modus operandi was to set the scene up, describe it, and just leave it there for the reader to judge for themselves. I was trying to not get emotional, to just present the facts from my point of view. From time to time I might have gone off on extended gonzo riffs, especially when I was describing the gigs that I attended as a teenager. But that’s me having fun as a writer. I decided I was just going to let myself go in these parts. I wanted to pass on the revelatory joy of listening to certain artists and the epiphany of the experience. I wasn’t scared of letting myself go emotionally.

“No matter how well I’ve done, I’m always that little kid playing on the streets of Springburn in the 60s. I will always have that feeling, that attitude, that insecurity, and that anger” – Bobby Gillespie

JH: It’s magical – when you’re describing the gigs you went to, it sounds like you’re writing from the point of view of a fan. You talk about rock and roll as a religious experience.

BG: Yeah, when I write these extended gonzo riffs, I’m also having fun. It’s not to be taken too seriously. And the reason I had fun was because I went from being serious – writing about my parents and their marriage, and the violence on the streets of Glasgow – to writing about the joy of being in a town and buying new wave post-punk records, and then meeting other like-minds, and striking up a conversation because you like the look of their shoes or shirt. Those conversations would lead to friendships. These connections are vital. I was fortunate enough to have experiences like that. It never happened by chance; it was because I had a curious mind. I met other teenagers who also had curious minds about the world, and about culture, and that’s what I’m celebrating in the book. I’m celebrating counterculture, and there is no counterculture anymore. To quote Douglas Hart, now we’ve just got “over-the-counter-culture”.

JH: I want to go right back to the beginning of you writing this book. Why did you choose the title Tenement Kid?

BG: I wrote a song about 10 years ago, and it was me beginning to open up and write more biographically. I called it Tenement Kid because I thought it was a great title: it was about a kid that grew up on a tenement.

JH: I guess you can take the kid out of the Glasgow tenement, but you can't take the tenement out of the kid, right?

BG: That’s definitely true, because no matter how well I’ve done, I’m always that little kid playing on the streets of Springburn in the 60s. I will always have that feeling, that attitude, that insecurity, and that anger. You don’t have to be too well-versed in psychotherapy to understand that. But that kid is loved and protected and celebrated as well. It’s not something that I’m ashamed of – it’s something I’m proud of, you know? I came from the streets of Springburn in Glasgow, and I love those streets and I love that city, and I love the Glaswegian character.

JH: It was also interesting how long you remained outside of mainstream success, and yet how committed to your art and music you were. There’s a lot of time in the book that you spend on that part of your life, but there’s a real tenderness to how you write about that struggle. It’s like those formative years are as important to you as the breakthroughs.

BG: I’m writing about those times in an illustrative way, and what I’m trying to illustrate is my commitment to being an artist above all else. For me, it was either earn a living as an artist, or go back into manual labour of some sort.

JH: So why was acid house so important?

BG: The main reason for Primal Scream is that, through acid house, we met Andrew Weatherall, who produced most of Screamadelica.

JH: I love that story in the book, when you go to hear him DJ and you refer to it as “a pagan summoning.”

BG: In the late 80s, if you were into alternative music, you were paddling around aimlessly in a sea of fucking nothing – nothing exciting was happening. There was some good stuff, like the Bad Seeds and Sonic Youth, but it was sporadic. It was at that time when American college rock was big, but when you went to see these bands play the energy was on stage; it wasn’t really in the audience. But when you went to an acid house gig, the fucking energy was in the audience. The DJ was stoking up the fire, but the fire was happening on the dancefloor, and the stars were on the dancefloor.

JH: This idea of total participation.

BG: It was a really sexual thing. There were just girls letting themselves go in this ecstatic reverie. This is what rock and roll in the 50s and 60s was like: this ecstatic, transcendent reverie in the crowds. And that didn’t happen in the 80s for rock music: the crowd were like sheep! Nothing against sheep – they’re beautiful creatures – but it wasn’t sexy going to rock gigs, whereas acid house was so sexual. This was where youth energy was in Britain in the late 80s and early 90s.

JH: You said ecstasy was no good for performing though.

BG: It was good for having sex with somebody, or for dancing. But I don’t think it was good for playing rock and roll.

“When you went to an acid house gig, the fucking energy was in the audience. The DJ was stoking up the fire, but the fire was happening on the dancefloor”

JH: How was it writing about drugs, and all of your drug experiences, with the distance that you now have?

BG: I had to put a distance between the way I live my life now and the way I lived my life then. I wanted to describe the usefulness of the drugs as a creative tool, or as a tool to dance all night long, to meet people, and how all of that was beneficial to me as a writer.

JH: But are you not amazed that you survived?

BG: Well no, because we weren’t taking ecstasy when we were in the fucking studio. We would never have got anything done! We were pretty together. I mean it was a line of coke here, a line of speed there, and if people went out at the weekend they went out at the weekend. But you need some kind of discipline, and people who party all the time don’t make good art – they’re too busy being off their heads. You have to get a balance. Some people in the band didn’t have the balance, but I’m still here. As time went on, through the 90s, my personal experiences with drugs became more extreme and I do think it did eventually have a negative impact on my work in terms of concentration. I wasn’t as rigorous as I could have been. But in the book, I’m writing about a time when it was all fairly new and innocent. We didn’t yet know how insidious hard drug usage is, and how it can deeply affect and change one’s character. If I write another book I may touch on that subject.

JH: How is performing and writing without [taking] anything?

BG: I could have never written this book, or my latest record, if I hadn’t been clean for a number of years. This is some of the finest work I’ve ever done, in my opinion. I would have never had the discipline to write this book before: I was a mess towards the end of my youth. So I’m much better – way happier now, in every way.

JH: I want to talk to you about style. It’s discussed a lot in the book, and you talk about how the way a band was dressed was equally as important as their music. What were some of the most significant images that shaped your early ideas of style?

BG: In the book I write extensively about Johnny Rotten. I remember seeing an image of him before I’d even heard the Sex Pistols music, and I was transfixed by it. It was all about his style: the clothes he was wearing, his aggressive stance, the look in his eyes, and his cropped haircut. I’d never seen anyone look like it before. It burned itself into my consciousness. And you have to try and compare what Rotten looked like in 1976 to anybody else in pop culture at that time: the era was dominated by the Eagles and Fleetwood Mac, guys in double denim with big moustaches, shirts open to the waist and medallions. And Rotten was a collagist, with his 1950s Teddy Boy boots and his 1940s old man trousers and his 1960s short, collared mod shirt which had been distressed. He also had a haircut like a guy who had been in solitary confinement – he looked like a deserter from the French foreign legion.

JH: I love it when you wrote that style is survival, that it is a way of asserting one’s individuality in the face of straight conformity, and that it’s a kind of street theatre. I just love the energy of that writing.

BG: Personal style is a form of psychic and cultural armour. That whole passage isn’t meant to be taken too seriously, it’s just about celebrating that street style and that individuality. Back in the day, when I ran with this kid Rab H, he had incredible style. He had nothing, but style gave him a way to walk through the world with his back straight.

JH: You dedicate the book to Robert Young and Andrew Weatherall, and you say thanks for the trip. What did you mean by that?

BG: They were my soul brothers and we had many great adventures together. By ‘the trip’ I mean the creative journey we undertook together beginning with Screamadelica and everything else that led in from that. I had a deep connection to both of them and I still feel their presence with me.

JH: One of the reasons I wanted to do this interview is because you’ve been such a great influence on me creatively. You, the band, and Screamadelica came out the same year as the first issue of Dazed, so for me, your album was really the sound of youth rebellion. And I just really liked the way that you collaged ideas in that album in such a powerful way, so I wanted to say thank you for the inspiration.

BG: Thank you. I think we were ahead of the times with that record. That was 1991. When we went over to America they didn’t know what box to put us in. [American accent] “Are you indie, are you rock? Are you dance?” I would say, “we’re everything really”. And they could not get their head around it. Then in 1998, 1999, The Chemical Brothers, Prodigy and all of these bands exploded all around the world. I think we were 10 years ahead of our time. At least.

JH: I think you’ve always been in your own time.

BG: [Laughs.] At that point we were somewhere else.

Tenement Kid is published by White Rabbit, and available to buy now.