In my early twenties, out of impatience with my life and a sudden sense of certainty that made my head feel clear as caffeine, as cold rain, I developed a bloody-minded desire for details.

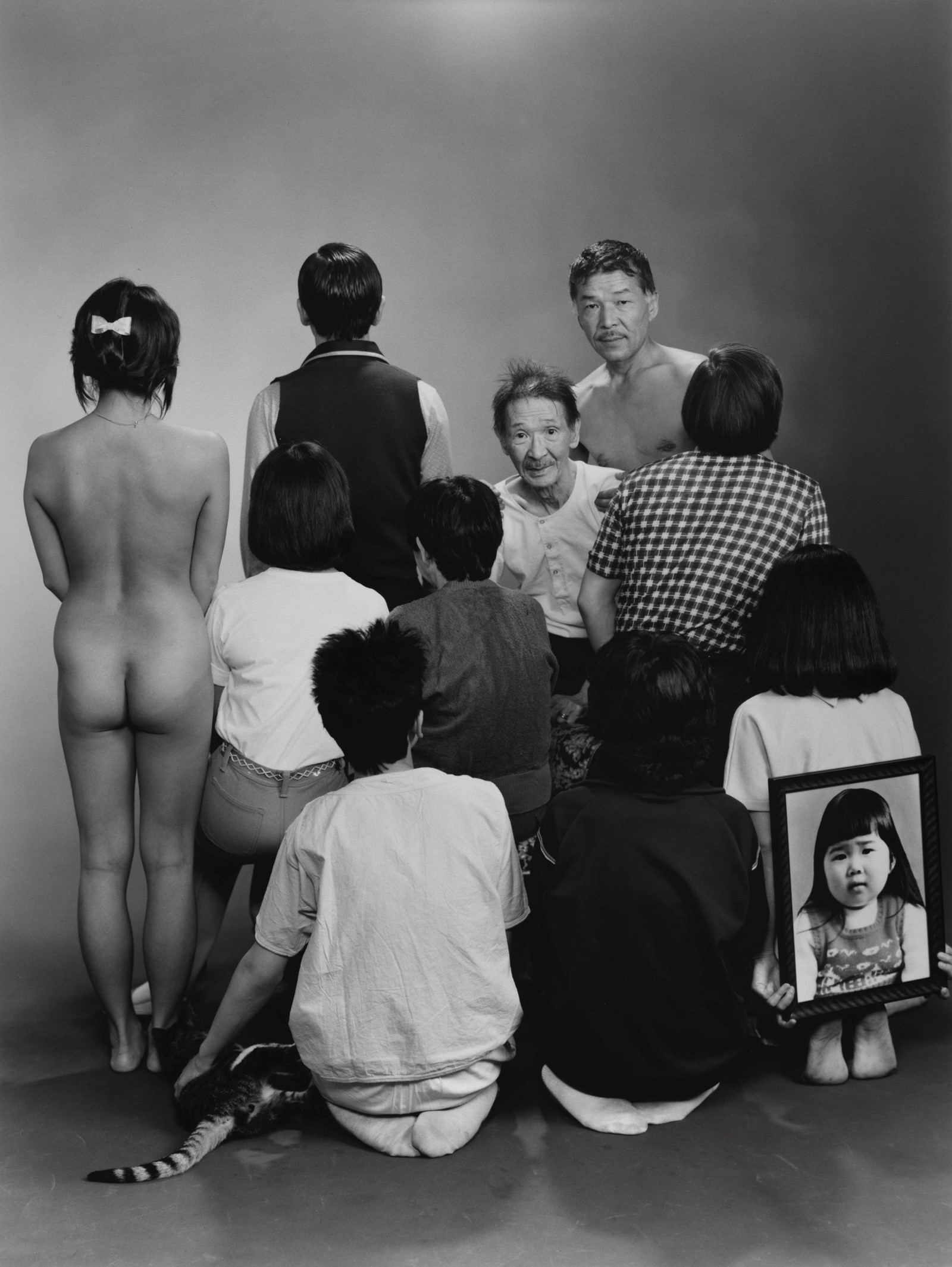

Writing comes on at thresholds, gateways where all the contours of a world we’re leaving behind are illuminated in a glare. But if we write to prove our agency at moments the self pulls against the environment that made it, and tries to assert its own edges, the casualty is often family.

The Polish poet Czesław Miłosz summarised this process with diplomacy: “When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.” As I started putting together this piece, wondering if there was something irreconcilable in being a writer and being a member of a family, I sent out a call to authors. The reaction was instant: many volunteered to answer my questions, and I supplemented their contributions with conversations I’d had in the past. The writer Jen Calleja was forthcoming, freely admitting in a message, “A lot of my writing is trying to express and work through feelings and experiences from my childhood”. But most others wanted to have their stories anonymised. On that condition, one author wrote to me: “I found what Patricia Lockwood said in Priestdaddy, about how much easier her childhood would have been if she’d known her only job was to notice rang true, and I worked that out quite young.” Another author and editor observed, frankly, in the tearoom of a hotel, “I’d hate someone in my family to write a book.”

The family is a narrative-forming machine, and accounts within it, even those that are obviously fantastical, accumulate legendary importance over their repeated retellings. My grandparents once took a road trip from France to rainy Wales based on my great-grandmother’s belief that we were descended from Sir Lancelot. There is a silent agreement in families to honour the collective story – dissent must be short-lived, or muttered quietly then ridiculed. In this context, a writer is a parasitic individualist, a tell-tale, a petty, self-indulgent control freak with one foot in, one foot out.

As Don DeLillo wrote in White Noise, “The family is the cradle of the world’s misinformation. There must be something in family life that generates factual error. Over-closeness, the noise and heat of being. Perhaps even something deeper like the need to survive. ( … ) Facts threaten our happiness and security. The deeper we delve into things, the looser our structure may seem to become. The family process works towards sealing off the world. Small errors grow heads, fictions proliferate.” The author who sent me this quotation commented, “Isn’t that the antithesis of what writing feels like?” Her question prompted one of my own: we tend to see family as foundational and fiction as make-believe, but what if it were the other way around?

The issue is partly a practical one: can anyone claim to be a proper participant in the family, let alone deserve to use family lore, if they are observing over their Weetabix? “I was worried they’d think I was a sneaky person who was always writing things down – which would be a fair judgement,” a novelist told me. Her mother’s reaction to her book was as much jealousy as a charge of duplicity: to tell her she herself could have been a writer. Childless forms of kinship are just as vulnerable in the face of fiction. In the winter, the novelist and essayist Madeleine Watts emailed me: “Nearly all the women I’ve known to publish debut books in the last year or so have broken up with their partners (but only if their partners were also writers).”

The trouble with writers in families partly hinges on a tendency Joan Didion identified: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images.” Especially if we are writers: writers live more entirely through this tyranny, Didion insists – but that doesn’t discount the other people who need stories too, and dislike their experiences being redrawn along the writer’s narrative line. One author went further, telling me her novel was partly drawing on “my desire for some kind of revenge. That was all in the book in the form of some kind of feverish fantasy.”

Many of the authors to whom I spoke presented their family’s response to their books as accusatory. “I’m very worried about what you’ve done to your uncle,” was one mother’s first comment, though the description to which she objected turned out actually to have been based not on the uncle, but a beloved if grotesque politico. Relatively flattering portraits, mixing familiar interpersonal dynamics with the iconic traits of cultural figures, were deemed cruel. In fiction, betrayals are difficult to map. While nothing is concerning (or, at least, threatening) in your son writing a history of the radiator, and memoirists can be held accountable by those around them, fiction-writers assemble their work according to strange logics – the way the language feels or sounds once it’s written down – pulled along by currents they don’t fully grasp: to be funny, to serve a plot, to shadow characters who are amalgams or never existed.

Working with the unconscious seems to be at the core of writing, and of course the family is very formative in that regard. One writer put the unconscious front and centre in her answers. “I started Jungian analysis earlier this year,” she says, “and I have begun asking the question whether writing the book actually was a plea to be seen and heal the wound. Did I unconsciously hope that my mother would read this and feel the truth of it, see what I had lived through, even if the characters were nothing like us?”

She continues: “I named the character of the husband after an uncle who I absolutely detest. I didn’t even realise it. Everyone in my family was sort of going on about it. I had actually forgotten that was his name.” She adds, “It is hard to feel truly responsible when I am not entirely convinced the book came from a place I have access to. Am I letting myself off the hook? In a way I suppose I only felt a responsibility to the story, which had its own internal ecosystem.”

A fiction writer is, on some level, proclaiming their desire to play with uncertainty and transformation, maybe even trying to find out how they feel. But reality is even more ambiguous than fiction: relationships change, they move, they exist in time. Fiction only seems to pin things down, the way a photograph both captures the soul and reveals the unnerving impossibility of doing so. Presumably, for a writer to be any good, the narrative line described by Didion needs to be flexible, to stir and shift with perspective. Sometimes I think, superstitiously, that the shape of a sentence is the shell of the experiences that produced it, and that I will need to keep having new experiences. I once expressed this fear to an editor at a party who warned that it might result in “Ted Hughes behaviour”. Another writer told me I had experienced enough, and now I had to go over it all.

Ultimately, it is alchemy – not just the use of material from experience, but its alteration – that can feel alive, to me, on the page. “My stories usually get so twisted in the fictionalising process that I don’t think they should ultimately be a problem for anyone but they probably are,” one writer remarks. In another author’s novel, based on events in her family, “the bones of it are salacious and true but the flesh is entirely imagined.”

Fear of familial reaction can make the process of writing fiction harder: to do so relies on being able to believe in your own freedom, a freedom that’s hard to balance with domestic allegiances: “The rule of ‘write like nobody is ever going to read it ever’ seems key.” A writer working on her second book told me: “I used to be able to tell myself that no one would read what I wrote and that made me feel ‘free’. It is harder to do that these days.” Another was convinced someone would be badly hurt as a result of her writing her novel. Her mother told her that her dad might kill himself when she got a deal.

The search for fragile freedom may explain the importance of literary community, a surrogate family that imposes different ethics to the nuclear family. The artistic communities that writers find can teach them to also give attention, patience, and energy to those closest to them. “I love collaborating with people, it’s something I learned from playing in DIY punk bands and from working with authors and editors translating German-language fiction,” says Calleja.

All the writers I spoke to had tactics to mitigate the destruction they feared their work might cause: waiting for deaths, avoiding using other people’s raw trauma, acting responsibly toward a community – producing more characters with different gender or racial identities, for example – and even asking individuals for permission. After the period of alienation between writer and family, they find a new footing.

“My mind is elsewhere some of the time,” one novelist writes to me. “On the other hand, it also enables me to do the work I do within my family (general support, translation – not literal – and listening) … I have more authority in family conversations now, which is weird ... I also have some family members who are under the illusion that debut novels are in a Hollywood situation and are subsequently jealous.”

At the extreme end of this ability to integrate possibly contentious material into family life, and to do it in real-time, one writer expressed the idea that writing, rather than being solitary, is a deeply generous act of understanding. “Which I experience in my family – open lines of dialogue and communication and the desire to understand one another and the world around us.”

For me, it isn’t so instant. Every part of this process takes time. I think that imposing a story on others is the basis of narration, and that it’s a good idea to acknowledge that from the beginning. Despite coming from a family that values books highly, and from parents who have their own writing and translating projects, I still feel I have to distance my work from them. Yet it would be dishonest to pretend that telling stories is an individualistic pursuit. My family is where I heard stories first: being told guilty moments my mum remembered from her childhood; being read to by my dad when he came in after work in his suit, or by my grandfather as my sister and I coloured the squares on a sheet of graph paper into a mosaic. When I was writing my first book, I was convinced everyone around me would suffer, but as my grandmother was dying she told me at lunch that I couldn’t do otherwise than to use my life. These days I’ve noticed myself holding on to notes for longer before transforming and publishing them, giving experience time to become material and hoping for that clarity I had in my early twenties again, the way you hope for rain.

A member of a family publishes a book. Behaviour around her adjusts, there are fewer unconsidered moments, but now some deeper stories emerge. Are her family telling her these so that she will set them down? Her mother embarks on a story the daughter shouldn’t repeat as she walks her daughter around a lake. The walk is an act of kindness: the lake is beautiful, the daughter would never have gone there alone; the daughter has been having a bad time and her mother is helping her. And yet, despite all this, the daughter records what she says.

The Weak Spot by Lucie Elven is published by Prototype, and is out now.

Lucie Elven has written for publications including the London Review of Books, Granta and Noon. The Weak Spot is her first book. She lives in London.