As the Candyman remake arrives in cinemas and Deep Cover, Jungle Fever and Menace II Society celebrate three-decade anniversaries, James Balmont explores the 90s ‘Golden Age’ of Black cinema

With the hit release of Jordan Peele and Nia DaCosta’s horror remake Candyman late this summer, a wave of critically-acclaimed and financially successful Black cinema continues.

So recognisable, in fact, are the likes of recent Academy Award winners Black Panther, Get Out and 2016 Best Picture winner Moonlight, that it’s easy to forget that it was only in 2015 that the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite went viral after the Academy awarded all 20 acting prize nominations exclusively to white performers. The Oscars repeated the same lamentable snub the following year, but thankfully, ceremonies since have been marked by increasing diversity. And as the wider industry takes slow steps towards a future that’s more inclusive, audiences have voted with their Monzo cards to support a breadth of films that reject white homogeny.

Wind back to 30 years ago, and Black cinema was in the midst of a similar ascendency. With Do the Right Thing and Boyz n the Hood, directors Spike Lee and John Singleton laying the foundations, a new wave of Black filmmakers would temporarily disrupt the white monopoly of Hollywood with their own brand of cinema. These were stories directed by and starring African-Americans, set in traditionally Black neighbourhoods like Harlem, New York and South Central LA, scored with Black music, and featuring Black perspectives and experiences otherwise ignored by mainstream cinema. Come the early 90s, Black films were not simply being financed – they were also producing significant financial returns at the box office.

“Just about every studio in town has a project in development with a Black director … or wants to,” read a March 1990 New York Times article, titled In Hollywood, Black Is In. And truly, Black culture would experience a meteoric rise in terms of mainstream visibility in the years that followed. The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air became a television hit, running for 148 episodes between 1990 and 1996 – as then-broke rapper Will Smith became a bankable acting star via films like Bad Boys. African-American music like hip hop and gangsta rap, meanwhile, transformed radio as NWA, Public Enemy, Dr Dre and Tupac registered major hits – just as fellow rappers like Ice Cube, Queen Latifah and Ice-T were establishing themselves on the big screen.

By the late 90s, Black actors like Wesley Snipes, Samuel L Jackson and Denzel Washington had become global stars, cinema superheroes and even Academy Award winners, as the 90s Golden Age of Black cinema petered out having confirmed its place in film history. With Bill Duke’s Deep Cover, Lee’s Jungle Fever and The Hughes’ Brothers’ Menace II Society celebrating three-decade anniversaries this year via BFI and Criterion restorations – as Tony Todd’s 1992 Black slasher icon Candyman also re-enters the public consciousness – 2021 now provides a fresh springboard into this vital 90s mainstream cultural insurgence. A vibrant journey begins below.

Do the Right Thing, 1989

An untouchable entry point to the “Black New Wave” of the late 80s and early 90s remains Spike Lee’s sweltering New York pinnacle, Do the Right Thing. A racially charged tale of a vibrant Black community and an Italian-American pizzeria during a heatwave in Brooklyn, the film is ripe with memorable characters, rich colour imagery and a soundtrack built around the sample-heavy hip hop of Public Enemy’s Fight The Power.

Boomboxes, bling, bright clothes and New York slices serve as a vivid snapshot of late 80s East Coast America – but the film also introduced the dynamic and astute craft of director Lee to a wide audience, put race relations to the fore, and even picked up two Academy Award nominations. Moreover, with supporting performances from the likes of Samuel L Jackson, Giancarlo Esposito (Breaking Bad, The Mandalorian) and John Turturro (The Big Lebowski, Barton Fink) – all of whom would collaborate with Lee for years to come – it provided a lofty benchmark for all Black cinema that followed.

Lee rolled out almost a film a year in the aftermath, with the critical and box offices successes of Mo’ Better Blues (1990), Jungle Fever (1991; re-released on Blu-ray by the BFI in May 2021) and Malcom X (1992) confirming the director’s place at the centre of the Black cinema revolution. More than 30 years later, Lee’s still on top – he headed the Cannes Jury this year, after 2020 Black Vietnam war drama Da 5 Bloods was recognised by the Oscars and the Baftas, among others.

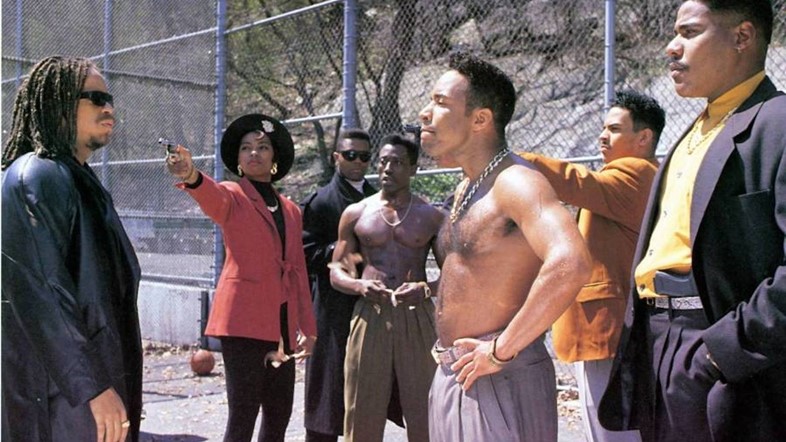

New Jack City, 1991

In 1971, Melvin Van Peebles directed Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song – a hallucinogenic tale of a Black pimp on the run which, alongside Gordon Parks’ Shaft, sparked a 200-film-strong boom in Blaxploitation cinema that decade. 20 years later, Melvin’s son Mario directed his own tale of Black entrepreneurialism set at the height of the crack epidemic in Harlem, New York. And New Jack City’s legacy was no less impressive.

The film opens with a news commentary that alludes to an escalating turf war between rival gangs, before cutting to the sensational killing of a white man dropped from the side of the Brooklyn bridge by crack kingpin Nino (Wesley Snipes). From there, we’re introduced to Ice T’s fearsome cop Appleton and Chris Rock’s perspiring drug addict Pookie, as an ensemble of emerging stars light up the screen. It’s a towering chronicle of megalomaniacal drug lords and perilous crack houses, replete with Kangol berets, big suits and bling – and while the pacing is erratic and the plot full of clichés, New Jack City brims with action and atmosphere.

While Brian de Palma’s Scarface is referenced several times throughout the film, Thomas Lee Wright’s original treatment for New Jack City was actually commissioned as a draft for The Godfather: Part III. After bringing in around six times its $8m budget at the domestic box office it became the highest-grossing independent film of 1991 – and the subject of countless rap verses. In 2019, Warner Bros announced plans for a reboot.

Boyz n the Hood, 1991

Four months after the theatrical release of New Jack City, John Singleton’s directorial debut traded New York for South Central LA in a coming-of-age tale that cemented Black cinema for a generation. Featuring a powerful turn from Laurence Fishburne as a hard-talking Vietnam vet determined to keep his son (Cuba Gooding Jr) out of trouble through strict paternal guidance, Boyz n the Hood was recognised with two Oscar nominations – making 24-year-old Singleton the youngest-ever filmmaker, and first African-American, to be shortlisted for the Best Director prize.

“One of every 21 Black American males will be murdered in their lifetime,” reads the opening titles of this tale of street violence, temptation and hard life lessons. It’s a death sentence that hangs over the film’s focal characters, introduced as children in the Stand By Me-style opening act – where troublesome ten-year-old Tre, fearless fatso Doughboy, football-loving Ricky and afro-haired Chris discover a dead body hidden in a back alley. Seven years later, with the boys schooled by their various experiences with sexual desire, juvenile detention and gang affiliation, adulthood and responsibility beckon – if only they can surpass the violence and crime that plagues the ghetto they call home.

Drawing heavily on Singleton’s childhood experiences, this landmark text introduced the wider world to harsh urban realities experienced by Black citizens in low-income areas across America. It featured breakout roles for Gooding Jr. and rapper Ice Cube (whose track Boyz-n-the-Hood for NWA inspired the film’s title), and a stellar soundtrack that fused the delirious jazz fusion of Stanley Clarke with West Coast rap and R&B. But the film’s legacy is perhaps best summed up by Barack Obama, who, via Twitter, testified upon Singleton’s death in 2019 that Boyz n the Hood “opened doors for filmmakers of colour to tell powerful stories that have been too often ignored.”

Deep Cover, 1992

Director Bill Duke might be better known for brutish acting roles opposite Arnold Schwarzenegger in both Commando and Predator. But as a director he made a huge splash in 1991 when crime-comedy A Rage in Harlem (starring Forest Whitaker) was nominated for the prestigious Palme d’Or at Cannes. A year later, Duke returned with the brilliant and underrated crime noir flick Deep Cover – which threw Boyz n the Hood standout Laurence Fishburne into a violent world of drug lords, double-crosses and duplicity as a begrudged undercover cop in LA.

Fishburne, later of The Matrix, and only a year prior to receiving a Best Actor Oscar nomination for Tina Turner biopic What's Love Got to Do with It, is a compelling lead in this gritty crime drama – and his co-star is no less captivating. Portraying the role of a crooked lawyer and formidable cocaine trafficker, and described as “so wildly out of place … he becomes [the film’s] greatest asset” in the Washington Post in 1992, is Jeff Goldblum – himself only a year shy of turning in a career-defining performance in Jurassic Park. As an unlikely tag-team of morally dubious drug-runners in cahoots to take down the top dogs, their presence trumps even the many dramatic set pieces, beat downs and courtroom climaxes.

The film’s soundtrack, meanwhile, is of unique historical relevance. Title track Deep Cover, also known as 187, was the first solo single from Dr Dre – and includes the first commercial appearance of a rapper then known as Snoop Doggy Dogg. The single was due to appear on the former NWA. member’s three-time platinum-selling debut album The Chronic but was abandoned after another track about violence against law enforcement, the Body Count single ‘Cop Killer’, drew controversy.

Menace II Society, 1993

Like a fatalistic counterpart to the coming-of-age tale of Boyz n the Hood, Menace II Society arrived in 1993 to deliver a gritty take on life in the Black neighbourhood of Watts, LA. It is the story of Caine, a young Black man born to a crack fiend mother and a murderous, drug-dealing father (played by a pre-Pulp Fiction Samuel L Jackson). “When the riots stopped, the drugs started,” he remembers of his childhood, in the aftermath of the racially-charged Watts Riots of 1965. “Sometimes Mom would use ‘em all up before he could even sell ‘em … Then he’d have to beat her up.”

While the vivid colours and lights of whiskey-soaked parties and reefer-fugged living rooms would contribute to Lisa Rinzler winning an Independent Spirit Award for her cinematography, the most memorable facet of Menace II Society is undoubtedly its bleak and intense violence. Beyond the many car-jackings, drive-by-shootings and gang-bangings, no moment is more visceral than the film’s shocking opening, in which “America’s nightmare” O-Dog – another Black youth who “didn’t give a fuck” – brutally murders two Asian liquor store owners in an unprovoked attack. It’s a scene that remains terrifying to this day.

Made on a budget of $3.5m when directors Allen and Albert Hughes were just 20 years old, Menace II Society was originally slated to star Tupac Shakur in a supporting role – but the rapper was fired after an on-set altercation with the directors. The film, nonetheless, went on to premiere at Cannes – before raking in $30m at the box office.