There are precious few spaces on the internet that you can read articles as wide-ranging as “Is Space Gay?”, “Am I Hooked on Male Validation?”, “Top 5 Rat Movies I Made Up”, and “Do I Have a Latino Fetish?” without changing websites – and that’s the beauty of ¡Hola Papi!, the “preeminent deranged advice column” from writer, author and “Twitter-addled gay Mexican with anxiety” John Paul Brammer. As touching as it is funny (and occasionally unhinged), it began life as a column on Grindr’s LGBTQ+ digital publication Into. “I named it ¡Hola Papi! because it’s something that a lot of Latino guys get from people on Grindr, this moniker of “Hola Papi” – you know, it’s a little bit fetish, it’s a little bit sexual. Insulting is way too strong a word, but it’s a little bit silly,” says Brammer, speaking over Zoom from his home in New York. “I thought it’d be fun to turn that on its head a little bit and use that as the title of my column.”

Initially, the idea was for it to be a joke column, but then Brammer started to receive serious, heartfelt and even intense letters. Pushed through Grindr, Brammer was introduced to the global LGBTQ+ community and the various, sometimes very difficult challenges they are confronted with in their day-to-day lives. “I realised I needed to take it more seriously,” he says. “And so that’s why it’s kind of funny. It plays with the fourth wall, but at the same time, it’s very heartfelt. All of its origins kind of come into play when it comes to writing the column – it has to have a little funniness, a little weirdness and a little sincerity. That’s still very much the recipe.”

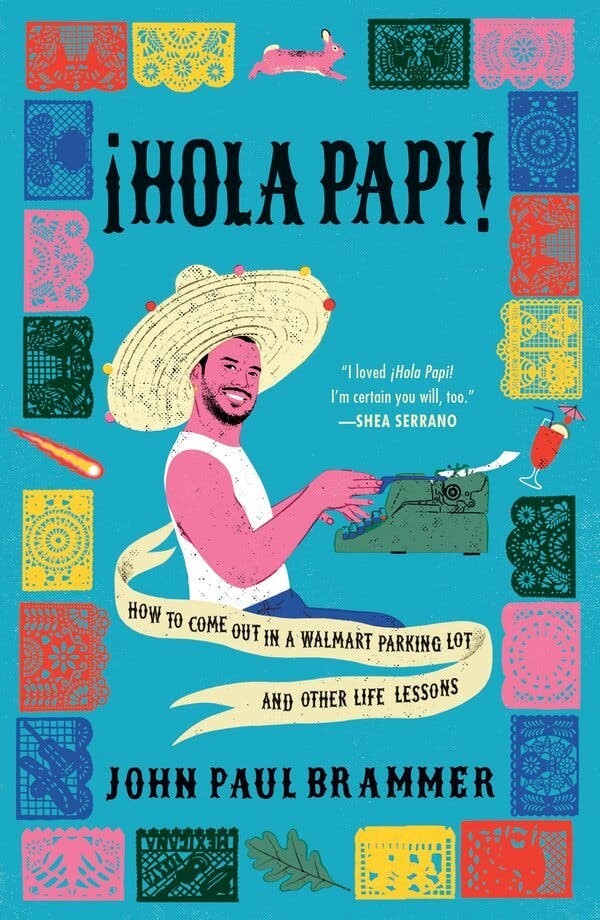

Now living on Substack, Brammer’s column has amassed a cult following (which includes this writer) and has recently taken on printed form in his book Hola Papi: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons (Simon & Schuster), which, in a series of essays, chronicles “his journey growing up as a queer, mixed-race kid in America’s heartland to becoming the ‘Chicano Carrie Bradshaw’ of his generation.” With all the wit and wisdom of his column, the book is a hilarious and heartwarming memoir of modern queer life – and a testament to Brammer’s talent and creativity as a writer. In the wake of the book’s release, Brammer opens up to AnOther about the story of ¡Hola Papi!, how he feels about being the internet’s agony uncle, and the piece of advice that changed his life.

Ted Stansfield: Have you always been someone that people have come to for advice?

John Paul Brammer: That’s what’s funny – not at all. I mean I’ve always been a supportive friend, but that’s different to people approaching me and being like, “hey, I need your help with this problem.” That’s a weird position to be in. The book is about me finding myself in that position and being uncomfortable with it. It opens with me getting a really intense question in a coffee shop in Brooklyn, and wondering, “OK, what about my life lends itself to me being able to give someone else advice?” It’s me rifling through some of the more prominent stories of my life, and wondering if all they can culminate into a CV of some kind to actually be able to give someone advice. What I find, in the end, is that they don’t.

TS: Now that you’re known as an advice giver, do you find that people – and I’m thinking specifically of strangers here – tend to open up to you about their problems a lot?

JPB: My friends, no, which I find really funny. They never ask for Papi advice. But strangers? Yeah. I do find my DMs filled with problems, and it’s upsetting to me because I can’t actually help these people. The advice column exists as a public artefact. It’s something that a lot of people are meant to look at and get something out of – it’s not me trying to fix one specific person, it’s me creating a piece of writing. But I’m not very good at [giving advice] on the spot – I need so much time to put a piece together. If someone asks me on the spot, like “what do I do?” I tend to freak out and be like, “oh god, I don’t know.”

“The advice column exists as a public artifact. It’s something that a lot of people are meant to look at and get something out of – it’s not me trying to fix one specific person, it’s me creating a piece of writing” – John Paul Brammer

TS: Going back to that idea of authority and of what qualifies a person to tell another person what to do or how to do it, over the years, people have written to you about very real, very heavy and very intense issues. I wonder how you feel about having that kind of responsibility as an advice giver?

JPB: Yeah, I’m very lucky on that front, in that I am both lazy and anxious. So if I find that I get a letter that is too [much] for me, I’m just like “I don’t really feel like tackling that.” That keeps me from putting my foot in my mouth. Because I think if I was even just an ounce less anxious, I would probably tackle all sorts of questions. A lot of them are very heavy and very intense – and of course you want to write a response to those because those are the big ones – but I’ve often found that I actually don’t know what to say there, so I have to forgo it. Most of the letters that I do write a response to tend to be ones that are a little bit abstract – they hinge on identity or expression or reckoning with their past or moving on. Those are subjects I’m comfortable with and I think the language I use in my writing lends itself to them because I enjoy giving texture and weight to abstract thoughts and ideas. I think that’s where I shine. And I think that is medicinal in a way, because a lot of people don’t necessarily have the language that they’re looking for to contain their problem. And if they did, then they could think about it in a different way and that is hugely therapeutic. I think that’s where I’m most helpful. I’m probably least helpful when I’m doing the whole, “break up with him, sis” sort of thing.

TS: Your column first ran in Grindr’s digital magazine, Into. And in your book you talk about your relationship with Grindr – I wonder how that relationship has evolved, and what it looks like now?

JPB: It’s a lot healthier nowadays because I approach it with a lot more whimsy. I used to approach it as if it was this thing that could validate me at any given moment. So if I was feeling unattractive or lonely, I turned to it in the hope that it could supply me with something. And that’s a really horrible way to approach Grindr, or any dating app, because other people are very unpredictable. They’re bringing their own baggage to this veritable nightmare playground of anxieties. You’re in for a bad time if you have expectations out of Grindr. Nowadays, I approach it with [an attitude of] like, “yeah, if something happens out of it, that’s fine, good for me,” but I don’t need something to happen. That has been very helpful to me because the fewer expectations I have, in general, the happier I am.

“I was on my way [to my first homecoming dance] with my mom and I told her I was really afraid. She was like, ‘oh, nobody will be looking at you,’ and I think about that all the time” – John Paul Brammer

TS: Obviously this is a book of life lessons, of advice. I wonder if there’s a piece of advice that someone has given you, which has been particularly impactful?

JPB: When I was in middle school – I went to a middle school in rural Oklahoma, out in the middle of nowhere – I had to go to my first homecoming dance and I was really anxious about it. I was on my way there with my mom and I told her I was really afraid. She was like, “oh, nobody will be looking at you,” and I think about that all the time. Because it’s helpful. There’s a difference between someone seeing you and someone seeing you as a person, seeing all your dimensions. Those parts of yourself are pretty well hidden, actually. So people can have their impressions of you, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that’s who you are. So I think a lot about my mom telling me that nobody will be looking at me like that. But then, on the other hand, that night at homecoming, they were drawing names out of the fishbowl for who the homecoming king and queen were, and they happened to draw my name. So in the end, a lot of people did end up looking at me. [Laughs.].

TS: Are you able to take your own advice?

JPB: Not really. I think that the Papi voice is very helpful because it’s a more confident, healthier voice than the one in my head. So it’s fun to step into that character and tell the jokes and be earnest and display all the emotions that I would like to on any given basis. But I have much more freedom because it’s on the page and I have complete control over what goes on to the page. So I think that that is a separate voice from the one that I use when I’m making my own decisions in my everyday life.

TS: I’m a big fan of the Still Processing podcast and I’ve been thinking a lot about this thing that Jenna [Wortham said] on their episode about Are You the One?. She said, “I do think there’s something about having a queer orientation that pushes you to look at yourself and understand yourself, not always, but a lot of the time before you ever even start dealing with someone else’s drama.” And I wondered if that was something that you agreed with, or that resonated with you?

JPB: Absolutely. I think when it comes to how we express ourselves in the world, how we move through it, how we interpret other people’s reactions, all of that is deeply informed by our early experiences that teach us that we might be punished for looking or acting a certain way, or expressing a certain thing. But the way you dress, the way you move, the way you talk – all of that is language. And I think that queer people have to be more fluent in it than other people, because we have to navigate more tight ropes to meet each other to, find each other, to avoid violence etc. And I think it means that we have to be hyper-aware of how we utilise language on a daily basis. And that naturally means, of course, having a more intricate relationship with it. It’s been the case for me and the people that I meet, where we’ve had to negotiate way more with the reality around you than other people have. And that sort of lends itself to picking more closely when it comes to yourself.

TS: Finally, what’s the feedback on your book been like?

JPB: It’s been overwhelming. It seems like every day that I get an email from someone who has been touched by the book, and it’s quite a ride, because I still don’t know how to respond when I hit something that’s positive and emotional. I have a little folder in my email that I send them to. They make me happy, and I enjoy getting them, but at the same time, part of me recoils a little bit. Maybe I don’t want to disappoint that person by engaging too much or maybe I don’t want to get too close because I might run away or something. But yeah, I keep them all and maybe on a stormy day I’ll need to take them all in.

Hola Papi: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons by John Paul Brammer, published by Simon & Schuster, is out now.