What exactly is a “missing person”? This question lies at the heart of journalist Francisco Garcia’s debut book If You Were There: Missing People and the Marks They Leave Behind (Mudlark), which explores the missing persons crisis which has exploded in the past ten years. Because it deals with such a multifaceted problem, the book is expansive almost by necessity – it takes in everything from homelessness to modern slavery, mental health, addiction, and young teenagers being roped into the drug trade. None of these problems take place within a vacuum, and If You Were There offers a sharp critique of the ways that the UK’s social fabric has been dismantled over the past decade. There is no longer much of a safety net for anybody.

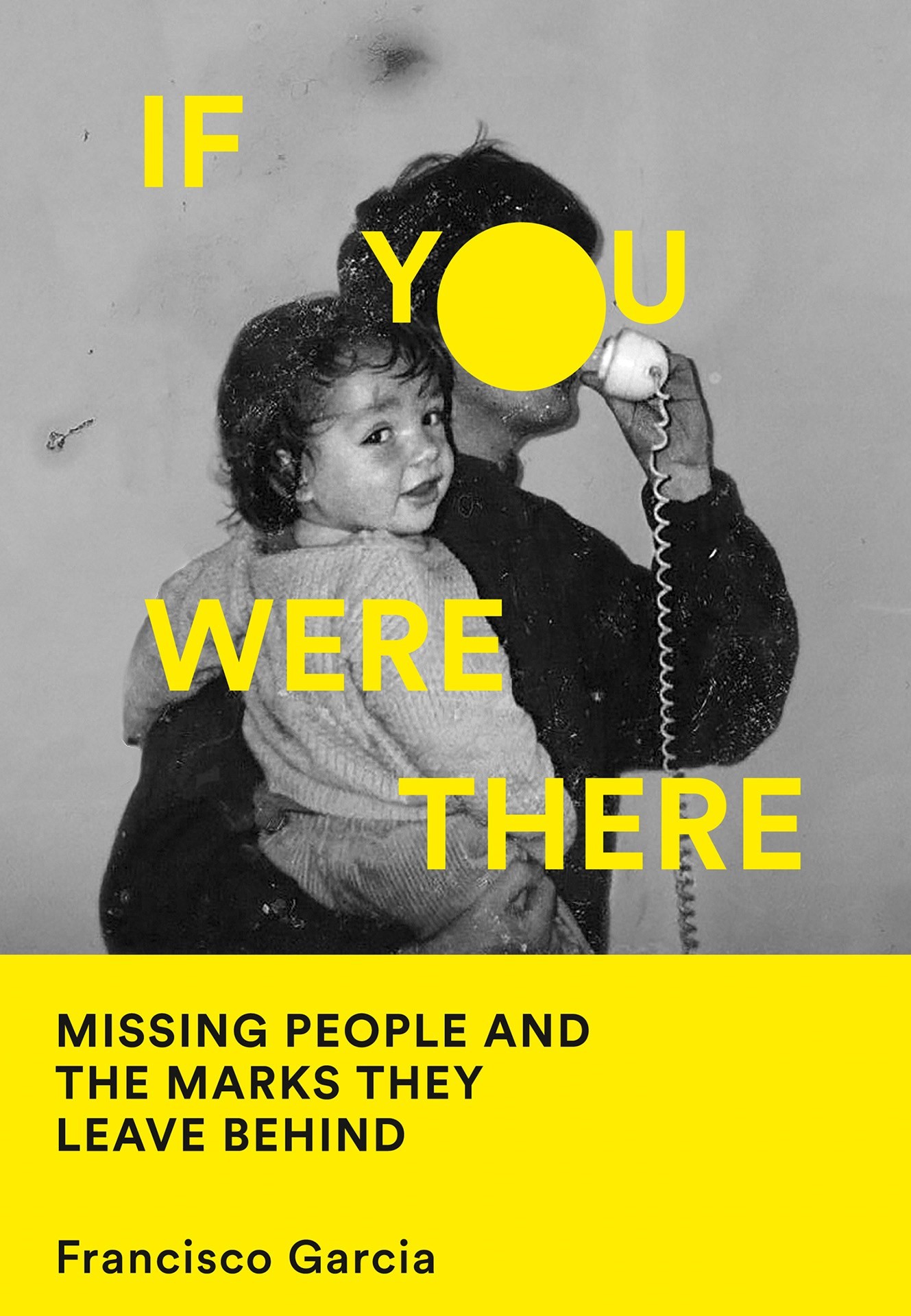

But as well as a portrait of a society in crisis, the book is also a moving and beautifully written memoir which deals with loss, grief, and the story of Francisco’s own father’s disappearance, not long after the death of his mother. You could be forgiven for thinking this sounds like prime “misery memoir” material but it’s not like that at all: Garcia reflects on his (objectively pretty difficult) experiences with generosity, dry humour and a refreshing lack of self-pity. I spoke with him to talk about what’s causing the missing persons crisis, the role social media plays within it, and more.

James Greig: What is a “missing person”? And why is that such a difficult question to answer?

Francisco Garcia: It’s one of these questions where it depends on who you ask. Police have one idea. And even within police, they have different attitudes towards it: some believe it’s wildly over reported, some people believe that it’s under reported. Charities will have a different definition. And of course, loved ones and people left behind by the missing will have a different idea as well. I tried to keep a strain of ambiguity in the book because I don't have the answer. When I started writing it, I came to things with the same misconceptions that a lot of people have. We all grew up with this particular cultural idea of missing people – you only ever really saw it reported if it was about abduction or a particularly harrowing case of someone who’s ever been found, right?

I also would say, and I can’t stress it enough, that I have never thought of myself as an expert on missing people, because I’m not. Even though I’m a journalist as well, I’m writing from a layman’s perspective. I wanted to get across this idea of there being a spectrum. Because, it’s amazing that this state exists, which is maybe the closest thing we’ll ever know to a third state between being alive and being dead. When you’re “missing” you’re in neither camp. But that range of experiences covers everything from a teenager who’s gone out drinking with their mates in the park, and is home a bit later than their curfew, right through to someone who’s been abducted, and something dreadful is happening to them. It clearly encompasses a hell of a lot of stuff. So how could there be a clear answer? How could there be one definition that encompasses all of these incredibly disparate experiences?

JG: One of the aspects of the book I found quite troubling is the idea that being active on social media doesn’t provide any safety net or make it any harder to disappear from view. We may think of ourselves as being very connected but social media has done nothing to ameliorate the missing person’s crisis. Why is that?

FG: I don’t want to generalise but I think for a lot of us who use social media regularly and heavily, it does give birth to this quite fragile idea of connectedness, right? But if someone deactivates Twitter or takes a break, no-one’s keeping tabs on that. Really, it’s not a substitute for an actual interpersonal relationship. The social media companies have sold us this idea that their platforms have made us more connected than ever. But I think it’s a complete myth that this connectivity exists beyond the very superficial element.

“I’ve always been drawn to stories that don’t have a neat resolution – maybe because of my personal experiences, maybe not. That tension and ambiguity is what’s interesting to explore. It’s not about solving it” – Francisco Garcia

JG: What about people sharing posts about missing people on social media – can this not be a helpful aspect of it?

FG: For very good reason, we’ve recently seen a huge uptick in people showing missing persons appeals. I interviewed this very interesting woman who runs the Centre for the Study of Missing Persons at University of Portsmouth, and she co-authored a paper about the effectiveness of missing persons appeals on social media – their conclusion is that they don’t even know how effective they are. For example, say you see an Instagram story about a missing person. Think about how fleeting that experience is. You might even pause it on the picture and think “oh, that’s terrible,” but then seconds later you’re scrolling through again to your mate’s karaoke party and you’ve forgotten it already. Also, it’s not the way memory operates, right? You don’t see a picture and it’s screenshotted in your brain with perfect clarity. You might see a picture [of a missing person], and then literally pass them in the supermarket but they’ve had a haircut or are wearing a scarf.

Also, it’s important to be very careful about these things because they can have unforeseen consequences. For example, I interviewed a woman who was an admin in one of the biggest Facebook groups searching for missing people in the UK. And she told me on the phone that they’ve recently had a big uptick of situations where a man has shared a picture of his wife and children going, “they’ve gone missing, can you please help? I’m beside myself! Can we please amplify this and make it go viral and find my loved ones.” With the best will in the world, that might get 10k shares – but then it turns out that woman is fleeing domestic abuse. I don’t really share these appeals as a matter of principle. I’m not saying I’m above it, but because of the nature of my work I’ve had to think about it more.

JG: I wouldn’t describe this as a “true crime” book but in some respects it has some of the trappings of the genre. Reading the book I felt this real desire to find out what had happened in some of the cases you mentioned, and you never do, and there’s a sense of frustration that comes with that. But it also seems like that frustration is kind of the point. How did you deal with that lack of resolution as you were writing?

FG: You have to embrace it. I’ve always been drawn to stories that don’t have a neat resolution – maybe because of my personal experiences, maybe not. That tension and ambiguity is what’s interesting to explore. It’s not about solving it. I’ve tried to make the point that this idea of resolution and closure is a fantasy, right? And I think writers are very guilty of buying into that and trying to shoehorn the narrative. But it’s more interesting to embrace that ambiguity. Life doesn’t have easy resolutions a lot of the time: things are very complicated and open-ended.

JG: The book has, to my mind, a pretty strong political message. What would you like people to take away from it and think about after reading it?

FG: I don’t want to dictate to people what they should or shouldn’t think about certain issues. I tried to explain why some of this framework is crumbling without battering people’s heads with it, because people are intelligent and can draw their own conclusions. If someone reading it has experienced someone going missing or is dealing with some kind of estrangement, I would like to just give that person pause to think about the fact they’re not alone in this, and that it’s a common thing. It’s not shameful or embarrassing. I hope it will make some people feel less alone.

Also, I would like people to see the terrible things that have happened to the fabric of this country in the last decade or so: everything from housing to the shameful and disgraceful way people with disabilities in this country are treated. The missing persons crisis is a political issue, which is not divorced from the world at large. There’s a reason why so many people are going missing. Mental health support has been slashed to the bone. We can see how little provision there is for people experiencing domestic abuse.

It’s going to sound corny but I do honestly think we all have a responsibility to other people, as well as there being a political element. It might be as basic and silly-sounding as checking in with people around you, and talking to people, and trying to understand the pressures in people’s lives that might lead them to thinking that their best bet is to fuck off. People only go missing because a vulnerability has opened up in their life.

“If I’ve written it when I was 14, you’d get a very different bit of writing. But I’m 28. I’m nearly ten years older than [my dad] was when he had me. I want to put my arm around the guy! If I felt negatively, I wouldn’t have written it, because the world doesn’t need another book about ‘absent daddy’ – who cares?” – Francisco Garcia

JG: The book deals with some very bleak subjects but at the same time, there is this strange allure to the idea of chucking everything up and clearing off. Do you think there’s something appealing in the idea of going missing?

FG: That must be one of the most ancient impulses people have. There are times when life is difficult, say you’re stressed out about a personal relationship or even just if you’re bored. I’m not saying it’s the same thing as going missing but I have a terrible habit of fantasising about moving to different places. I’ll go on Reddit and type in, “what’s life like in Philadelphia? I might move there,” despite the fact I know nothing about it. Of course, there are times when there is a very natural and enduring impulse to think, “what would it be like to just walk out for a bit?” But that isn’t even the same thing necessarily as going missing – that’s very normal.

JG: I found the portrayal of your father in the book to be very generous and humane, and completely without bitterness. How did you go about narrativising and characterising him?

FG: Well, I tried really hard. I never had any resentment towards this guy and I mean that sincerely, I’m not just saying that for effect. It’s not in my nature, I’ve never been a resentful person. It’s also because he didn’t wrong me. Nothing happened. How could I be angry at this guy? I was never angry. I felt very sad for him, more than I felt sad for myself. Which is actually a very weird and bad emotion to feel about your dad. You don’t want to pity your dad, but I did pity him. And I don’t mean that as like, “he’s a creature of pity” – I felt a real pity for him.

JG: I think it’s more empathy or compassion, right?

FG: I felt compassion for him, because he didn’t have it easy. Neither him or my mum had it easy, they were people who didn’t have a fair chance in life. And he must have been about 21 when he had me. I think about him more and more these days. It’s just like, yeah, how could I be angry? What is there to be angry about? If I’ve written it when I was 14, you’d get a very different bit of writing. But I’m 28. I’m nearly ten years older than he was when he had me. I want to put my arm around the guy! If I felt negatively, I wouldn’t have written it, because the world doesn’t need another book about “absent daddy” – who cares? That’s a very outdated trope. That’s not interesting.

If You Were There: Missing People and the Marks They Leave Behind by Francisco Garcia, published by Mudlark, is out now.