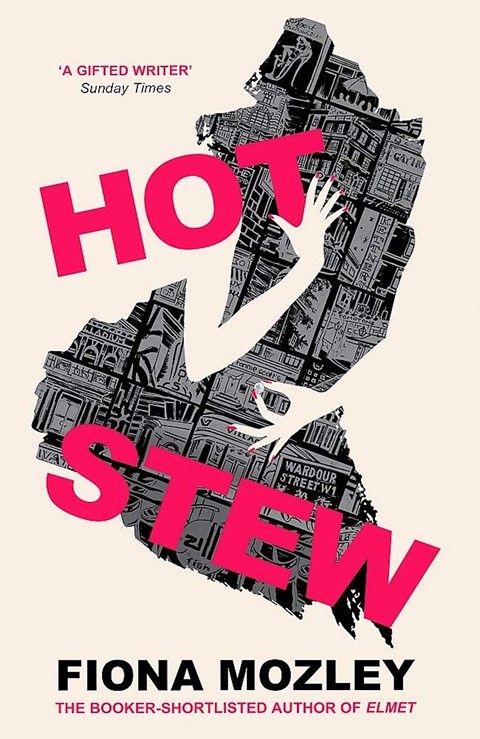

The Booker-nominated author talks about her newly released second novel, Hot Stew – a raucous celebration of Soho’s forgotten inhabitants

In 2017, Fiona Mozley stunned the literary world with her Booker-shortlisted debut, Elmet. The noir novel was a suffocating study of gentrification and property ownership, following a family living self-sufficiently in the wilds of Yorkshire.

Elmet’s long-awaited follow-up, Hot Stew, was released earlier this month. Although set in the bustling heart of London’s Soho – worlds away from the forests of the north – it deals with many of the same issues as its politically-charged predecessor. Like Elmet, Hot Stew explores the ways we find, shape and protect our communities, and the external forces that threaten their existence. It tells the story of old Soho’s survivors – sex workers, ex-cons, addicts and cult leaders – as they navigate new, increasingly hostile forces in their neighbourhood.

As well as being a love letter to London, Hot Stew is also a eulogy: a bittersweet farewell to a city being swallowed by billionaires and capitalist property developers. For 33-year-old Mozley, who was born in the capital but now lives in Edinburgh, it was a subject that felt particularly pressing, both politically and personally. Here, she reveals more about the novel’s inspirations, as well as her hopes and fears for London’s future.

Dominique Sisley: When did you decide to become an author? Why did you want to write about these issues?

Fiona Mozley: I never really knew that I wanted to be a writer, and I still only vaguely consider myself to be a writer. I started journaling and travel writing when I was in Buenos Aires teaching English. And then, when I moved to London in the spring of 2013, I started writing my first novel, Elmet. At the time, I was working at a Flight Centre travel agency, which didn’t really suit my personality – it was very sales driven, and you had to be quite extroverted. But a friend of mine knew someone who had a cheap room going on Dean Street in Soho. There wasn’t a contract, because it was a 17th-century building that was covered in scaffolding and liable to fall down, so it was all a bit dodgy. But it was absolutely amazing. I was there for four months until the council found out and I had to leave. By that point, I’d had enough of London.

“I thought the property bubble would have burst by now, but it’s just getting bigger and bigger. It’s terrifying” – Fiona Mozley

DS: A lot of people tend to give up on London. How do you feel about the city now?

FM: I had a great time there, but it was just quite difficult. I don’t want to create some sort of sob story: I was living with other graduates and we were all fine, we all had jobs, we all had our health. But it was just such a precarious living situation. It was a case of constant movement, going from houseshare to houseshare.

DS: I’m guessing that’s why you felt compelled to write Hot Stew, as it’s all about that ambient instability of London living.

FM: Yeah, I’d say so. Both of my books have been concerned with property ownership and people struggling to find a home or creating a home for themselves. Property ownership is obviously a huge issue; there’s a huge class divide with it ... And it’s important, when you’re talking about gentrification, to keep the conversation focused on people rather than whether or not the neighbourhood is aesthetically pleasing. People should be able to develop communities in a longstanding way, rather than being constantly worried about having to move somewhere else.

DS: There does seem to be a clear gap forming when it comes to property ownership in London. You either have to have had substantial help from parents, or be extremely well paid – and it seems increasingly likely that anyone outside of these categories will just be forced out of the city.

FM: I thought the property bubble would have burst by now, but it’s just getting bigger and bigger and bigger. It’s terrifying ... I’ve got friends who decided to take their Cambridge degrees and become social workers or teachers – professions that society really needs – and they’re not able to contemplate buying property. It’s just the lawyers, really, that can. Good luck to them, but we can’t have a society that’s completely full of lawyers. I think graduates should be commended for going into professions that do good in the world.

“I wanted to create this sense of the city consuming itself, and I wanted that to be a metaphor for capitalism” – Fiona Mozley

DS: Gentrification and property ownership are profound, complex issues. How did you approach the vastness? Did it take a lot of research?

FM: I read a lot of fiction, and also nonfiction and politics books. I read a lot of journalism and memoirs, I watched political YouTube videos. I’m not really sure what constitutes research and what doesn’t, because sometimes a chance encounter or a conversation with someone, in a totally normal and natural way in the middle of Soho, will have a profound effect on you, and that’s not really research per se. But I always wanted this book to wear its artifice on its sleeve. It’s made up; it’s an alternative universe.

DS: There is a lot of unexpected surrealism weaved in, which adds to that “alternative universe” feeling. How else do you think that helps the story?

FM: There’s a grand tradition of writing about London in a surreal way. That’s what I was thinking, without sounding too grandiose. I wanted to create this sense of the city consuming itself, and I wanted that to be a metaphor for capitalism. So there are lots of metaphors in there: descriptions of eating and consumption, going down passageways and into the bowels of the city and being vomited out.

DS: Sex work is also a very important part of the story, too. Did you feel pressure to get that right, to honour the real-life sex workers of Soho?

FM: I really did try my best. My main focus was making those women well-rounded: I wanted them to be funny and intelligent, and also different from one another. I wanted to treat them like everybody else. I read a lot [about sex work], had a lot of conversations, and I wanted to be balanced. I didn’t want to glamorise anything, and I didn't want to present them as victims. I am totally convinced by the arguments for sex work decriminalisation, and there are many absolutely amazing activists who are much better placed to present those views and their policy ideas than me. I just wanted to present well-rounded characters who happened to be sex workers.

DS: It feels like a political fable in many ways. Are you comfortable with that classification? Would you call this an anti-capitalist book?

FM: It’s definitely anti-capitalist. I wanted to show how everybody is caught up in the system of relentless capitalism and gentrification. And while the book definitely plays on caricatures and is cartoonish, I was trying to present the system as the problem. It’s less about the moral failings of individuals … I am interested in these ideas because I feel angry about society in its present form. It just felt obvious to me to try and grapple with them.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Hot Stew is published by John Murray Press, and out now.