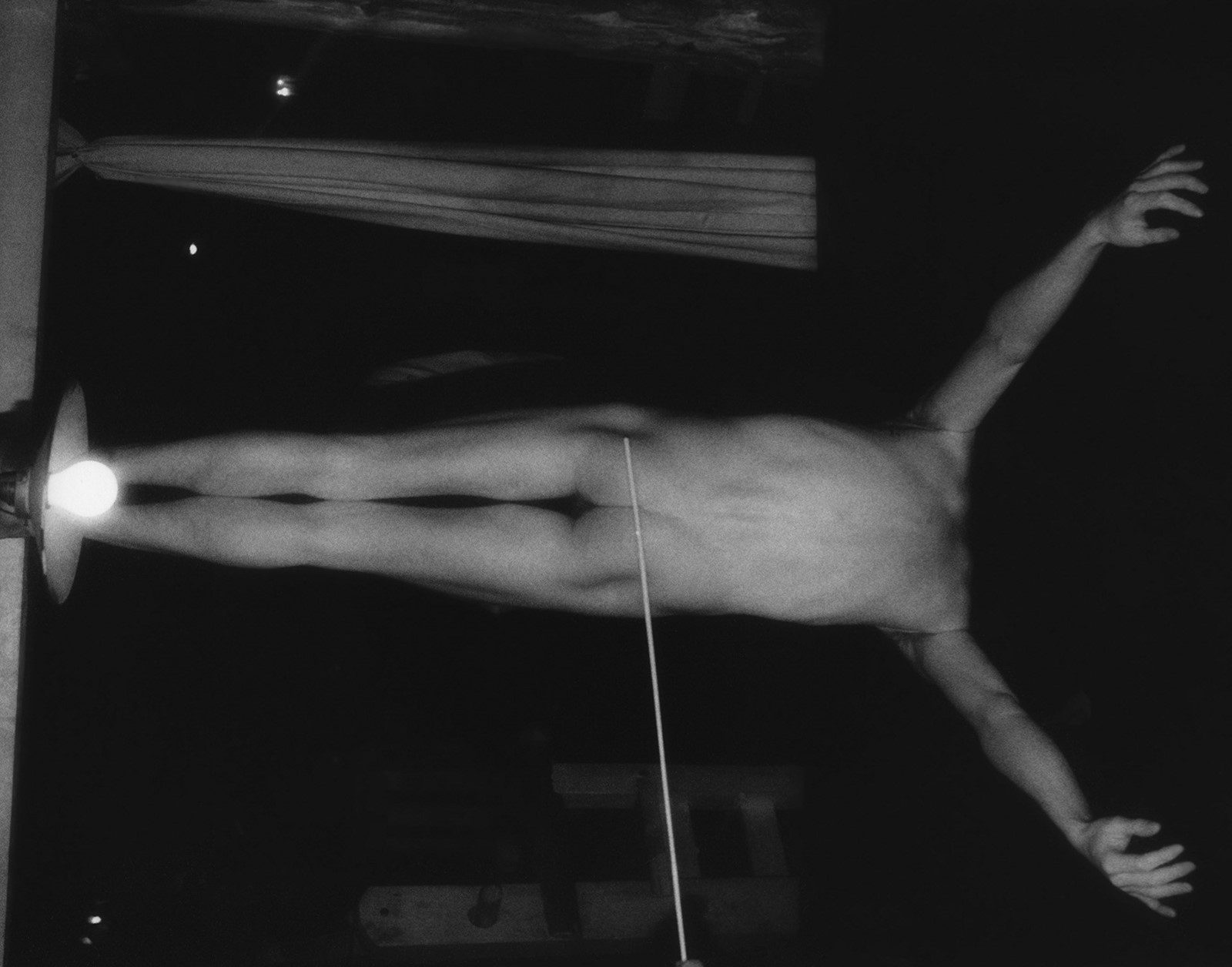

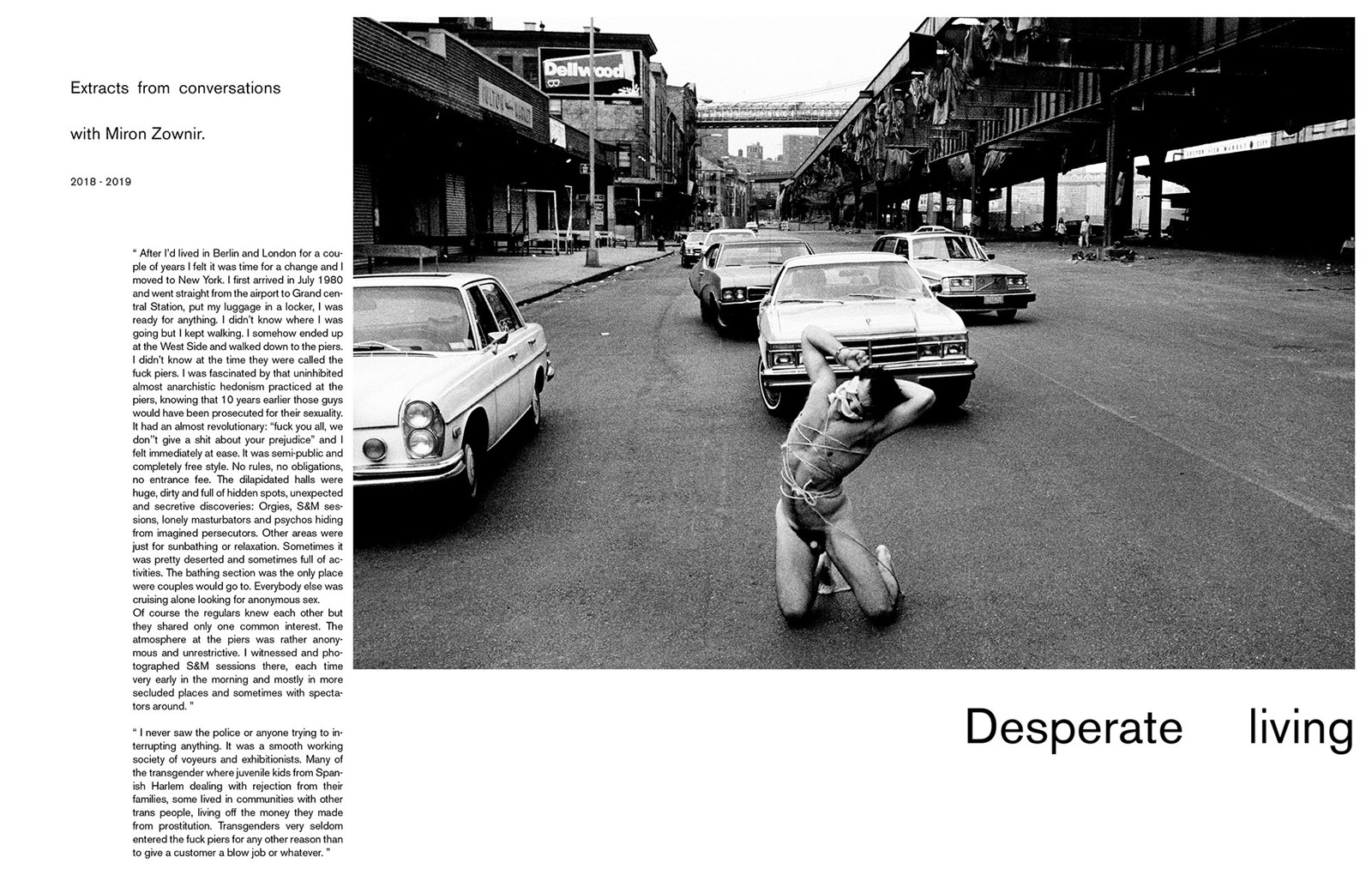

Pillage is an LGBTQ+ magazine – but not as you know it. Launched in February, it’s described as being “by and for sex-positive types”, merging, as co-founder Nicolas Santos says, “independent media, new online realities and historical context”. And it really is: the publication is a blend of the indie fashion magazines you might find at Wardour News (RIP); the ways we might think about and express ourselves sexually these days, particularly in relation to the internet; and reference to and reverence for LGBTQ+ history.

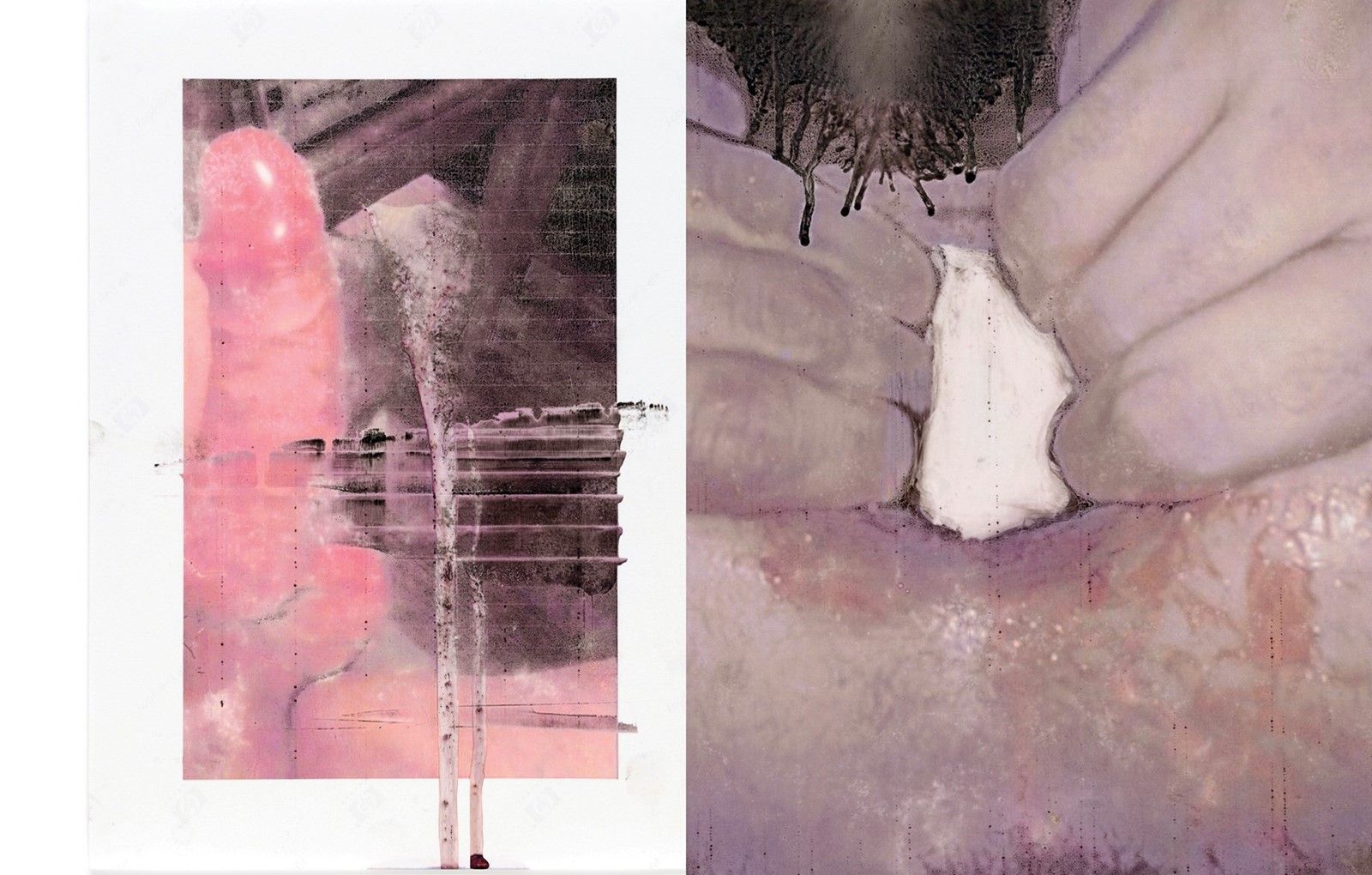

Pillage was created by Santos, a creative director and the founder of independent publishing house In Present Tense, and Benjamin Kirchhoff, who predominantly works as a stylist. Friends before they were collaborators, the pair came together with the aim of making a magazine that explores “personal yet unspoken realities surrounding sex”. “Pillage is a magazine dedicated to contemporary sexual culture,” explains Kirchhoff. “Our stance is not pornographic, nor apologetic. What we wanted was to create non-judgemental pages to discuss openly modern realities of sex practices, show living and complex artists, but also raise questions and generate ongoing dialogues with our readers. We want the magazine to be reflective of queer life realities – the good and the ugly. I see the magazine as much a portrait as a mirror.”

Out now, the first issue features interviews with the likes of Miron Zownir, Anton Stoianov, Hermes Cevera, Dan Kane, Michael Sayles by Stefano Pilati, and David Lindert. It feels new and yet familiar, intelligent but not intimidating. And as much as it is beautiful in its design, it’s practical too: the whole thing is littered with classifieds, contacts for community-based and non-governmental organisations, and information about queer archives, museums and libraries. As well as giving a voice to the lives and lived experience of LGBTQ+ individuals, the publication is also quite clearly about fostering a sense of collectivism, with “no projection, no idealisation, no censorship, and no filters.”

Here, Kirchhoff and Santos tell AnOther more about the project and what they hope it achieves.

AnOther Magazine: How do you know each other, and how did you come to make this magazine together?

Benjamin Kirchhoff: I met Nicolas back in 2014. I had a shoot commissioned for a magazine and Nicolas was the art director on the project. We met again when I moved to Berlin the following year and quickly became friends. We share a similar upbringing, similar life experiences and viewpoint, but in many ways we are very different people. It’s through conversing that we talked about doing this. Nicolas had at that point launched In Present Tense. Both of us had wanted to create publications based on personal yet unspoken realities surrounding sex: stigma, addiction, intimacy, but also attitudes, censorship, consumption, and culture.

Nicolas Santos: Berlin brought us together, but there’s a deep respect and appreciation for each other’s work, and many overlapping interests. Over the past years we started casual talks around life, death, and sex – as friends do – that quickly turned into more meaningful conversations. And we found that it was time for a new way of telling stories that are pushed to the sidelines but that form a big part of our identities.

“Both of us had wanted to create publications based on personal yet unspoken realities surrounding sex: stigma, addiction, intimacy, but also attitudes, censorship, consumption, and culture” – Benjamin Kirchhoff

AM: The magazine opens by saying that it is created by and for sex-positive individuals. What does sex-positivity mean to you?

BK: Personally, sex-positivity is an enlightened attitude towards sexual consumption and sexual outlook. I accept that I will always have much to learn from others, and therefore myself. It is deeply personal and ultimately comes with self-acceptance. But sex-positivity isn’t a recent “subcultural” phenomenon as many would like to have us believe. What is recent is the commercialisation and the digitisation of a visual culture geared towards one very specific consumer group.

NS: To me, sex-positivity is the realisation that we are driven by many forces that limit us in our sexual beings, and the desire to understand these forces in an open and constructive way. In more mundane terms, it’s your doctor being able to give you correct and comprehensive treatment without judgment, your partner being open to understanding and respecting you and therefore satisfying you. Or just simply learning to not be conditioned by what society expects of you and actively affecting change.

AM: In your editor’s letter, you discuss the raison d’etre of the magazine, but also your own sexuality, gender identity, and HIV status. Why did it feel important to you, and to this project, to disclose these things?

BK: For me that isn’t about disclosure. I make no apologies for my status but it isn’t to say I don’t recognise that there is still “that” weight attached to being positive. HIV is an undiscriminating reality, and each person it affects, deals with it in very different ways. Stigma is still a heavy and unfortunate reality that most of the people touched by HIV will have to deal with. I haven’t always been comfortable about discussing it, when I was diagnosed 14 years ago everything was set in a very different context, in general and in my life. To talk about HIV status, sexuality, or visual presentation isn’t a way to set myself apart or mark so called tribal allegiances. It is simply a way of acknowledging this reality in order to get past it: this is me … now what? It is also a levelling step with our contributors and readers.

NS: It is important to be in touch with one’s condition and relation to gender and sexuality in order to understand others. We felt we had to put ourselves into question from the start if this project was going to work and by doing it publicly it can allow for others to start that realisation privately. We don’t feel it’s necessary for anyone to disclose anything specifically, but there is a process one must go through and we wanted to honour that.

AM: The magazine brings together some amazing people – from artists, photographers and curators, to writers. What are some of the contributions that you’re most proud of or excited about?

BK: It is difficult to say, not that I want to be the mum who says she has no favourite kid … But this was considered as a curation. It was about having space for generational voices and different work methodology … we wanted to gather individuals who would not otherwise meet, and make space for questions and ideas to develop within the reader.

NS: Personally, I thought it was very interesting to see how, given the freedom to reach out and connect with others, people that submitted personal ads were not looking for sex but for meaningful personal connections. In an age of dating apps, the intimacy we crave is more complex.

Something I loved about the magazine was that it felt useful, practical. You have classifieds, contacts for community-based organisations and non-governmental organisations, and information about queer archives, museums and libraries, as well as a call out for personal and business ads. What was the thinking behind this?

BK: The idea was mainly to encourage greater engagement within local peer groups but to also foster direct dialogue between us and our readers. I’ve always liked directories of all sorts – they are to the point and anonymous. These community pages act as highlights throughout the magazine. They are a reminder to the individual and the community at large that one cannot exist without the other. I want to take this opportunity to encourage people to send us their work and stories.

NS: In our search for these personal realities, we found that many answers could be found already in the stories of people that came before us, or are next to us. Community, information, and culture are fundamental pillars of what we want to do. Allowing for these to take centre stage creates a richer environment where you are always exposed to different – yet similar – points of view.

“Pillage gives power to the individual, trusting that people want to connect on that personal level and are willing to discuss openly without taboos” – Nicolas Santos

So much of queer life is now experienced and expressed online – from the ways we connect and to the spaces we congregate in. Since the pandemic, even more so. What are your feelings about the digitalisation of queer identity and community and how does Pillage relate to this?

BK: I feel it is a double-edged sword, on one hand it offers contact, information, and potential opportunities, but on the other it is no substitute for many other things. The way we connect and the spaces we gather online? I think they offer only a fraction of the solution, especially since your interactions online depend on a series of algorithms. We have to acknowledge the importance of technology but we also have to remember it wasn’t always there and that so much can be achieved when individuals get together with a purpose.

NS: We live in an age of what feels like an overload of information. But this information is fed to us through companies that tend to look for the lowest common denominator, and punish stories that deviate from the norm. Pillage gives power to the individual, trusting that people want to connect on that personal level and are willing to discuss openly without taboos. Unfortunately this isn’t possible in the current digital landscape and a print project seemed for now like the only way forward. We had intended to create in-person events that best suit the purpose of the magazine, obviously this had to be postponed, but we are working on how Pillage’s mission can translate online and we are looking forward to being able to come together again. In that sense Pillage’s mission seems to be more urgent than ever, both online and offline.

What are your thoughts on the current state of LGBTQ+ publishing and where does Pillage fit within this landscape? It feels like we have the mainstream gay media at one end of the spectrum and then the indie fashion magazines (which despite often being run by and aimed at LGBTQ+ people, are ultimately still fashion magazines) at the other. Pillage feels like it bridges the gap between the two, in its directness about its queerness but its style; its beauty as an object.

BK: We don’t have to promote an artist or a brand so it makes it a lot easier to be cohesive and not compromise on either the content or the layout of the magazine. We could focus purely on content, idea development, message and graphics, and give appropriate space to each contributor. We also wanted to define an aesthetic that wasn’t going to depend on filtered codes for what queerness should look like.

NS: There’s a difference with wanting to portray a collective, and wanting to show their individual stories. We don’t aspire to represent any given collective, but show the beauty of personal individual differences. This is sometimes uncomfortable, contradictory, but we encourage these discussions. Focusing on only one letter of the LGTBQIA+ spectrum is also, we feel, detrimental to bridging those gaps between all our personal realities. This suited other times where representation had to start by building a collective, but we would like to take this further and show the richness of individual sexuality and identity in all its forms.

What is your hope for Pillage?

BK: I would like Pillage to carry on being a discussion tool for the community at large. As mentioned in the editor’s letter we need to be confronted by the reality of sex workers, trans individuals, asexual individuals … but also queer individuals who live outside the relative privilege of the western world.

NS: I hope it becomes a symbol of how people can unite through being unique, all while appreciating our differences. A manual for people to find common ground, and an instrument for respect.

Buy a copy of Pillage here and follow the magazine on Instagram here.