James Greig speaks to Jeremy Atherton Lin about his new book Gay Bar, the cyclical nature of nostalgia, the benefits of dark rooms, and the pathologising of sex and drugs

We’re now almost a year into a situation where bars and clubs are banned, which is either an unfortunate or brilliant time to publish a book about nightlife. On the one hand, reading about all the fun we’re not having is a tempting form of nostalgic escapism. On the other, being immersed in a world that was already endangered – and risks being lost entirely – could well prove a painful experience. With real-life sociality restricted, many of us have retreated ever further into the internet, where the “queer community” (something which, to my mind, does not exist as a coherent entity and least of all online) descends into rancorous and sanctimonious debates, of an intensity which is only really possible when you can’t see the person you’re shouting at. Many more have surrendered to the mundane comforts of takeaways, streaming platforms, and subscription services: I myself have been wearing the same grey hoodie-and-trackies combo for the past six months, feeling ever further removed from the possibility of glamour. At the moment it’s been made impossible, it’s never been clearer that real-life gay sociality is important.

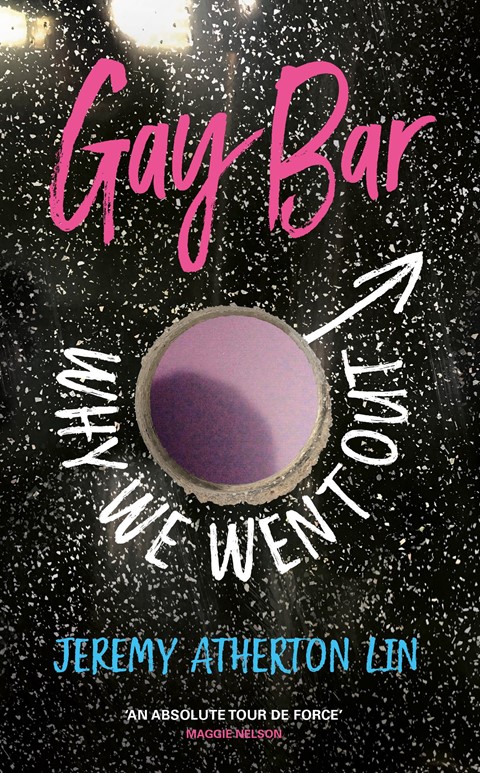

So actually, I think it’s a very good time to read about queer nightlife. This March sees the publication of Gay Bar, the first book from California-born, London-based essayist and critic Jeremy Atherton Lin, which offers an expansive history of gay bars; the buildings themselves and the cultures which emerged around them. Each chapter focuses on a different venue, which serves as a jumping-off point for a wider exploration of the history of three cities in particular: Los Angeles, San Francisco, and London. By now, genre-blending nonfiction is a well-established form and Gar Bar recalls the work of Maggie Nelson or Olivia Laing. But, even still, the scope of genre’s being combined here is impressive: it’s social history, queer theory, architectural and design history, literary criticism, travel writing, and a memoir concerning a decades-spanning romance. For all its erudition, it never feels contrived or overly-stuffed; it’s rich with quotations, but each one feels well-placed and interesting. The book is also funny, and often self-mocking, and I liked that it avoids making high-minded claims about the radical, transformative potential of going out. Something doesn’t need to be politically subversive to be worth defending; in this case, the fact that it’s fun is enough.

I spoke with Atherton Lin on Zoom last week, feeling that some dive bar in the Castro would have been a more appropriate venue, and we discussed the cyclical nature of nostalgia, the benefits of dark rooms, the pathologising of sex and drugs, and gay bars as sites of disappointment.

James Grieg: This is a strange time to be publishing a book about nightlife, but for me reading it in lockdown really worked. I felt a lot of yearning while reading it. Had you finished writing it before the pandemic happened?

Jeremy Atherton Lin: Yes, I was finishing when it was first kicking off. And we had to make a decision about whether or not there would be an afterword in it; but it just didn’t seem right for there to be an afterword in the first printing, because with any book, once you’ve written it, it leaves the author anyway. Now, obviously readers are going to be reading the book with that cloud hanging over it, and we just decided to let that be.

JG: One thread that runs throughout the book is this feeling of perpetually having arrived too late to the party. For you, that seems to be most evident in the sections set in Los Angeles and San Francisco. For me, the section set in East London during the 2010s was almost painful to read, as it’s an era I just missed out on. But you’re not really writing about that time-frame in a particularly romanticised way, although it’s a fond recollection. That sense of having arrived too late – do you think that that is a gay sensibility in itself?

JAL: I guess there’s a universal FOMO. The memoir section begins in 1992, and I do feel like a very in-between generation, like a lot of people my age do. The bars were very sterile at the time, because they were in the shadow of the Aids crisis and because they were trying to deflect the stigma of Aids. But I do think that by the time I got to Shoreditch in the 2000s, I truly did feel like I was in the centre of the world. There was kind of a feeling of like, “Oh, hey, finally!”, seeing Wolfgang Tillmans at the bar, all that kind of stuff … You would get used to it, but at first it was incredible. It was literally a magazine coming to life.

“... by the time I got to Shoreditch in the 2000s, I truly did feel like I was in the centre of the world … You would get used to it, but at first it was incredible. It was literally a magazine coming to life” – Jeremy Atherton Lin

JG: The book is a heartfelt eulogy or love letter to gay bars, but it also addresses the fact that they can often be quite cheesy or banal. At one point you write, “I learned the give in to the experience for what it is: tacky but effervescent, artificial, cut-throat, cringe.” How did you navigate that contradiction between portraying gay nightlife as something important while also acknowledging that the reality is often disappointing?

JAL: Well, a couple of things. There’s a part of me that’s quite fond of the mediocre gay bar in the centre of town that is largely for office workers, who might not want to stay out all night and aren’t extravagant club kids, but still want to let their hair down. I respect that those kinds of places need to exist.

But yeah, the cheesiness … you kind of have to embrace it. I’ve been thinking a lot about this: there’s a very popular idea currently which is like, “being queer is the best thing that ever happened to me, it made me who I am!” And I don’t think I ever felt like that. Growing up, I was weird and into music and different politically from most of the kids I went to school with in the California suburbs. I remember being the only kid in my class who raised his hand when they asked who was against the death penalty, for example, and that separated me as much as being gay.

Then you come into the gay identity, and it’s supposed to be this all-consuming thing, but actually a lot of what I see being prescribed to me about what gay is, I don’t really relate to it. In my generation, it was this very buffed-up, shaved-chest aesthetic, and I certainly didn’t find a home in that. But then as I aged, I came to have a sense of forgiveness about gay sensibility, because you just understand how it works in more intellectual ways; you understand what is a result of Aids, and what is a defence mechanism, or what is just finding joy after years of feeling fed up and repressed.

JG: One issue you write about in the book, in some ways quite critically, is the idea of turning gay bars into heritage sites and the various conservation campaigns which run alongside this. It seems like a lot of these campaigns are based around an idea of cultural significance which is unlikely to be extended to dark rooms or saunas. I worry that the pandemic could be the death knell for these more subterranean facets of gay nightlife, and that when they do close it’ll be with a whimper not a bang. Would you agree with that?

JAL: I think that over the last few generations, in various ways, gays have had to put their best foot forward, and present an anodyne image where gayness basically doesn’t belong to us anymore really. And that’s fine. Other people can have it: if a group of straight women want to feel safe while dancing and wearing feather boas in a gay bar, sure, that’s great. They can have it. But I think you’re right about saunas and dark rooms. What would the heritage project for a perverted space be? It’s kind of a contradiction in terms.

But yes, it would be a loss. Take somewhere like The Catacombs in San Francisco, a fisting club. Whereas today what mostly happens are these mobile, domestic, unmonitored situations like chemsex parties, a venue like The Catacombs was actually very self-monitoring. It was a safe space in a lot of ways, it was clean and considerate, there was a code of behaviour built into it.

“I think that over the last few generations, in various ways, gays have had to put their best foot forward, and present an anodyne image where gayness basically doesn’t belong to us anymore really” – Jeremy Atherton Lin

JG: The book portrays sex and drug use in a non-moralising and non-pathologising way. It’s never like “we were promiscuous, because we were chasing the love that we never felt from straight society!”, which is refreshing. It also presents the fact that you and Famous [Atherton Lin’s partner, pseudonymously named after a Leonard Cohen song] are in a non-monogamous relationship in a matter-of-fact way, offering no explanation or apology. How were you thinking about these themes as you were writing it?

JAL: It was important to me that there wasn’t a judgement placed on those non-normative behaviours. I’m glad you asked about Famous. Nobody ever asks me about that. I feel like Gay Bar is primarily a love story.

I’ve been predicting that some people might take issue with the “we” in the subtitle, because they think it means I’m attempting to speak on behalf of all gays. So for instance, if you were a monogamous, married, “homo-normative” gay or whatever then it might feel like a bit of an affront that the “we” in the subtitle seems to be suggesting that we all do drugs and have threeways or whatever it may be. But when we came up with the subtitle, it was very consciously really about me and Famous, or about a small gang of friends or about a larger network of friends in a city. I’m certainly not making a claim to speak for all gays.

Homosexuality can be private, but gay is a public thing. You can be homosexual on your own, but gay is a group activity. It was just very natural for me to not make a distinction between romance and sex. I don’t think that you have to compartmentalise.

JG: Even though you’ve said you felt quite alienated from the dominant gay aesthetic as you were growing up, the book is also quite critical of various attempts to escape from a normative model of gayness. For instance, the way you depict the ‘Popstarz’ era in 90s London [a gay indie night and attendant scene which consciously set itself apart from mainstream gay culture and allied itself with Britpop] and also the Gay Shame movement [a leftist, anti-assimilationist queer movement which opposed the mainstreaming of gay culture] which you depict as being ultimately kind of preachy. How were you thinking about this ambiguity as you were writing it?

JLA: There’s expectation in nonfiction that the narrator has a kind of authority and clarity of vision about the culture that they’re seeing, observing, and analysing. But sometimes I am an unreliable narrator. I have this stoned exhibitionist moment in the first chapter and, from there, I’m giving you a signal that I am goofy and impulsive and I don’t always have agency in the decisions I make.

It’s maybe a little disarming for a reader to have a narrator who can’t make up their mind or who sees both sides. In the case of a group like Gay Shame, I wanted to belong to it and yet there were reasons why Famous and I wanted gay marriage, and I found myself feeling disconnected from the politics. You want to belong and feel like you can’t, the moments of being included are fleeting. What you’re maybe picking up on is a kind of ambivalence and confusion; trying to give everyone the benefit of the doubt yet also being sceptical.