The 28-year-old author – hailed as the “next Sally Rooney” – talks capitalism, class and her scorching 2020 debut, Exciting Times

When Naoise Dolan’s debut novel Exciting Times was released last year, she was swiftly earmarked as the “next Sally Rooney”. The comparison was mentioned repeatedly in the book’s marketing materials, in reviews, in interviews, and in the 28-year-old’s author biographies. She’s a young Irish woman, after all, and she’d written a novel about love, self-loathing, and emotional repression. An excerpt of Exciting Times had also been published (and praised) by Rooney, during her brief stint as editor of The Stinging Fly magazine.

While comparisons to Normal People might be welcome, Exciting Times actually lives in its own, equally bright universe. It’s queer, for one thing, with a polarising bisexual protagonist and a humid Hong Kong backdrop. It follows a young Irish expat called Ava, as she becomes romantically entangled with two people: Julian, a filthy rich, emotionally stunted banker, and Edith, an ambitious, caring lawyer. Who will she choose? And what does that choice reveal about her relationship to power, sex, and her sense of self?

The classic love triangle trope gets subverted by Dolan’s spikey prose, which crackles with caustic humour and scorching one-liners. But her detached tone also belies a genuine, affecting fragility, giving Exciting Times an unexpected emotional punch. With the novel set for paperback release this week, we caught up with Dolan over email to discuss her inspirations, politics and writing process.

Dominique Sisley: How has the last year been for you? How have you been passing the time and dealing with everything?

Naoise Dolan: It’s been a hard year but I don’t know anyone who would say differently! No-one with a lick of sense, anyway. I’ve been coping, I guess, and dealing, and all those other verbs that were worn out before the first lockdown was over. More literally speaking, I’ve been writing new pieces, keeping up with media requests for the first novel, and, most recently, moving into a new flat in London that I’m renting with a friend.

DS: The protagonist in your debut novel Exciting Times, Ava, seems very similar to you on paper: She’s Irish, queer, she spent some teaching English in Hong Kong ... How much is she a reflection of you?

ND: I don’t think Ava reflects anything about me. I’m distant from all the characters I write, because I’ve seen all the scaffolding and how my choices can change from draft to draft and make them completely different. So it’s not even that I’m one type of person and Ava’s another, it’s that I’m a person and she’s words on the page. I hope those words create the effect that she’s real for readers, but because of the work I put into those words I can’t see her that way myself.

DS: She seems to struggle a lot in the novel with her queerness. Have you had to grapple with similar feelings of shame or repression when it comes to your sexuality? Would you say that’s still, even today, a common part of the queer experience?

ND: I think homophobia and transphobia are still endemic in society and until that changes, queer people will always have to gear our identity and choices around protecting ourselves. You can’t safely avoid bigots without learning exactly what they’re saying about you and how virulent they can be. So I don’t see hating queerness as part of the queer experience so much as part of the straight one: hating us is, for whatever reason, still common among them, and that’s borne out statistically in everything from media dogwhistles to hate crimes.

“People tend to divide relationships in quite a binary way, ‘toxic’ and ‘healthy’, when what’s more common in the real world is that different people bring out different aspects of each other” – Naoise Dolan

DS: I’m particularly interested in Ava’s relationship with Julian in the book – it seems loveless and pointless, but also quite sweet and moving. He is both archetypally awful (an emotionally repressed Eton banker) and yet somehow endearing. What does this relationship represent to you?

ND: It was important to me to show that she stays with him as long as she does for a reason, and the reader needs to feel involved in that reasoning. We enjoy lots of things that aren’t good for us, and having someone back up the worst aspects of your personality can be hugely enjoyable. In online discourse especially I think people tend to divide relationships in quite a binary way, ‘toxic’ and ‘healthy’, when what’s more common in the real world is that different people bring out different aspects of each other. I think that’s something worth observing without needing to have a take on it or label it good or bad, and that’s exactly what fiction does best.

DS: The book plays a lot with ideas of class and capitalism. It examines these themes, but also doesn’t seem to judge anyone too harshly. Are you a political person? How do you engage with these issues in your day-to-day life?

ND: Thank you! I think that’s what I aim to do – I want to write fiction that’s alert to what it’s like to be alive today, and for that reason politics come into it, but that doesn’t mean I’m necessarily advancing an argument – there is fiction that does that, and does it well, but mine is mainly observational. For me the most interesting thing about fiction is that it’s a world without consequences, and that means we can try to understand people without needing to pass judgement. In real life I need to work out who’s trustworthy, often quickly and without much information, but in fiction there isn’t that practical need to make snap judgements. You can take your time, let the different perspectives sink in. In my actual life I’d say I’m about as political as the average person, though of course that’s difficult to measure. I go to protests but I don’t think I’d ever have the skill set to organise one. I’m definitely not an activist. I know people mean it as a compliment when they refer to writers that way, but I think it does a disservice to actual activists and the intense, full-time, generally thankless work they do.

“I want to write fiction that’s alert to what it’s like to be alive today” – Naoise Dolan

DS: You were also diagnosed with autism as an adult – how did you feel about that, given how ableist society still is? Do you feel comfortable with it, or do you worry about being “labelled” or classified in some way?

ND: I worry about ableism, but I think where I’m at with it is that I know it will affect me whatever I do. It’s structured so you can’t escape it as a disabled person. Sometimes when people know I’m autistic they’re more understanding, and sometimes they bring unhelpful assumptions and treat me worse, and I can never be sure which it will be. So it’s exhausting having to calculate that every time I’m wondering if I should tell someone! But on the whole, I think “it’s not your fault” is one of the most powerful things you can tell someone who’s discriminated against. Especially with social communication, it’s so easy to internalise the message that you’re a bad person if you’re on a different wavelength to most people, so it makes me much happier and at peace in myself knowing that it’s not my fault if other people feel that way about me.

DS: You moved from Ireland to the UK, and attended Oxford University. What was it like being exposed to the English class system? How different did you find it to Ireland?

ND: It wasn’t really a shock, because I grew up reading mostly English books; if anything, the actual Oxford was a lot friendlier and diverse than the one I’d encountered in Waugh and so on. For the most part I enjoyed it! At Oxford, and in London since, I’ve found it’s really possible to find your people and go from there. There are things about the English I’ll always find a bit odd, though. In Ireland I’m regarded as shy and in England I tend to be seen as bubbly. My level of talking remains constant, it’s just that Irish people really can’t handle gaps and silences and so we’re very well-trained in small talk to fill it. I’m sure there are English people who find it overfamiliar or a bit forced, but when it flows it’s really lovely.

DS: And finally, what are you working on next? What are your plans for the rest of 2021?

ND: I’m doing edits on my second novel and thinking about the third, and I generally have a few other short pieces on the go as well. So my 2021 plan is to keep going with that as best I can, and hopefully not kill my new houseplant. It’s been three days and it’s not dead yet, so things are looking up.

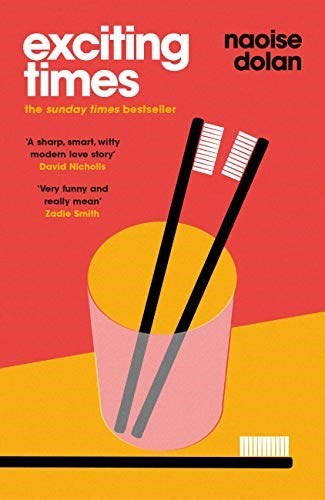

Exciting Times is published by W&N, and is now out in paperback.