The Barbican’s newly opened retrospective on Michael Clark is a remarkably comprehensive look at the dancer’s subversive career

This article is part of an ongoing series on Michael Clark, tied to the Barbican’s major exhibition of the radical dancer and choreographer: Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer.

As one month of lockdown has blurred into the next, the visceral thrill of live performance may feel like a distant memory. Anyone finding themselves in a state of ennui, however, need only head over to the opening rooms of Cosmic Dancer – the newly opened Michael Clark retrospective at London’s Barbican – where you’ll find something of a rude awakening.

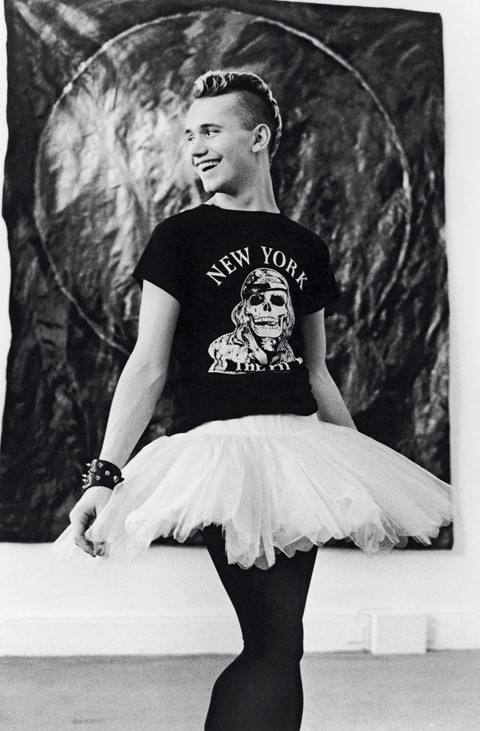

A constellation of giant screens are arranged at angles in a darkened space, providing a gloriously chaotic showcase of two of Clark’s late-80s “media-dance” masterpieces created in collaboration with Charles Atlas, Hail the New Puritan and Because We Must. Clark’s angelic features stare out behind surreal face-painted polka dots or thickly applied red lipstick, his lithe figure wearing a Vivienne Westwood Seditionairies “tits” tee and a tutu, or striking a pose in a flamenco-inspired, crotchless jumpsuit and a pair of graphic Y-fronts. The Fall’s Mark E. Smith, whose jangling post-punk guitars serve as the trippy sonic backdrop to the dancer’s off-kilter ballet moves, appears in one section as a disheveled TV show host. Even Leigh Bowery appears painted in head-to-toe blue; later with his mouth open in a scream, signature stacked glasses across his forehead.

It makes for a heady nosedive into Clark’s most brash and confrontative works, something that, as the exhibition’s curator Florence Ostende describes it, was very much intentional. “It was about finding ways of encountering the choreography that had nothing to do with the usual or straightforward way you might see it on the performance stage, but instead to present as this kind of immersive collage,” says Ostende of the opening installation, which was created specifically for the exhibition by Atlas.

Indeed, the only real way to tell the story of Clark’s career – with all its meanderings and ups-and-downs – is as something of a collage. The story begins with the boy who grew up a farmer’s son in Aberdeen, before his prodigious talent took him to the Royal Ballet School at the age of 13, where, despite wearing earrings and being caught glue-sniffing, kicking out their star pupil proved out of the question. Turning down an offer to join the company upon graduating, he pivoted to modern dance at Rambert, before quickly finding himself restless there, too.

Then, at the age of just 22, Clark formed his own dance company, where he could fuse the rigour of his multifaceted training with the freewheeling spirit of the underground London nightlife he found himself immersed in. “I think what makes him really special is that he has never rejected his ballet training, or the technical virtuosity of the work,” Ostende adds. “That’s what makes this mix of high and low so particular.” Yet while his work received pearl-clutching responses from the dance establishment – alongside a passionate following among a new generation of dancers seeking to break down the rigid parameters of the medium – for a period in the 90s, Clark all but disappeared. Battling a heroin addiction (and following that, an addiction to the synthetic heroin substitute methadone) he retreated to his mother’s home in rural Scotland to recover. Returning to London towards the end of the decade, he found that, due to missed payments on a storage unit, his archive had been entirely sold off or disposed of.

It’s this that makes the comprehensive nature of the exhibition all the more remarkable. That so many of these pieces were able to be sourced and put on display once again pays testament to the close bonds Clark established with a head-spinningly broad range of collaborators, all of whom held onto and treasured the fruits of their collective labours. Like the pioneering maestro of dance (and one of Clark’s heroes) before him, Sergei Diaghilev, Clark’s position as a truly groundbreaking figure in the history of dance isn’t the simple collision of classical ballet and punk, but his neverending fascination with the unlikely products of interdisciplinary collaboration.

“I was really interested in shaping the exhibition a bit like a love letter, or at least a compilation of portraits through the eyes of artists and friends and collaborators and heroes that had been revolving and still revolve around Clark’s work,” Ostende explains of the exhibition’s second half, which is divided up with works produced with a variety of these very collaborators, many of whom were closely involved in how they would be staged this time around. A particularly memorable room comes courtesy of Sarah Lucas – who supported Clark during his fallow years by offering him a job gluing cigarette butts to her sculptures – that includes a concrete cast of Clark’s lower half slumped on a toilet; a vision of the ballet dancer’s physique reaching middle age that contains both pathos and an eerie beauty.

There are also plenty of fashion treasures to be found: relics of Clark’s regular collaborations with the cult fashion label BodyMap, whose innovative designs emerged from the clubs alongside Clark’s radical dance performances, as well as glimpses across the videos of pieces by Alexander McQueen and Gucci. (A painting by the artist and club kid Trojan that inspired Atlas’s sets for Hail the New Puritan, meanwhile, was offered for the exhibition by Kim Jones from his personal collection.) Nowhere does Clark’s sprawling body of work feel more bracingly contemporary than in his democratic understanding of all forms of creativity, from classical ballet to streetwear design.

Part of this resonance with the present moment is more poignant, too. The hopelessness felt by Clark and his first generation of collaborators, and the fiercely political, anarchic artistic spirit that bubbled out of it, was partly the product of working under a right-wing Thatcherite government, whose cynical approach to the creative industries ended up formeting some of the most powerful British art of the 20th century. And despite being many years in the making, the exhibition’s arrival at a moment when funding for the arts is in crisis, with today’s Conservative government recommending workers within the creative sector to “retrain and find other jobs”, feels both profound and timely.

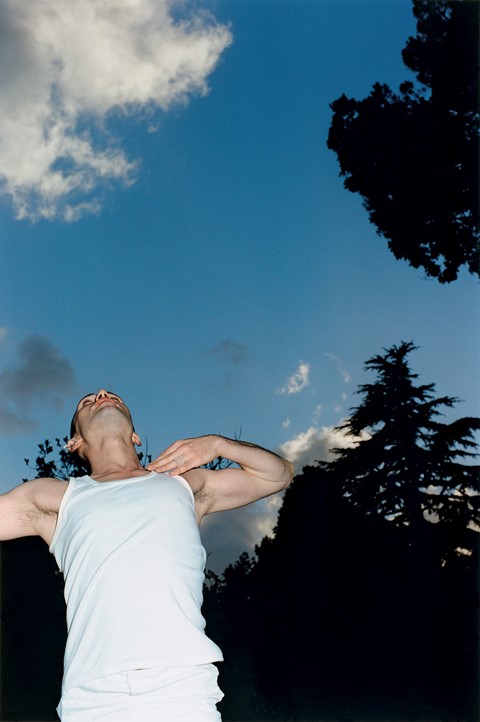

Yet despite these rich (and knowing Clark’s fascination with British history, likely intentional) parallels, where the exhibition feels most vital is where it holds its eye firmly on the future. There may have been an extensive series of live performances planned to accompany the show that have sadly been cancelled, but Clark and the curator’s wish for this inclusive, genre-defying creative universe to provide fertile inspiration to a new generation of creatives doesn’t feel unearned. With the extensive offering of videos on display, many of which have never been on public view before, it’s a world to get lost in – but ultimately, to be influenced by. “We didn’t want this to be an archival exhibition, we wanted to celebrate him as a living artist,” Ostende explains. “It’s about looking forward as well as to the past; about taking the exhibition into a second phase, and seeing it reinterpreted in the eyes of some of the participating artists.”

It’s partly for this reason that Clark has refused interviews around the exhibition, preferring to let the work exist as something in its own right. Still, in an interview with Ostende that is reprinted in the exhibition catalogue, Clark says, with typical impish humour: “You are aware that, for me, my work is a matter of life and death?” With Cosmic Dancer, Clark’s extraordinary body of work feels ready to be passed onto the next generation – even as it remains, in its own right, fiercely alive.

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer is at the Barbican, London, until January 3, 2021.