A look at some of the films that cemented Takeshi Kitano’s name as one of Japan’s greatest contemporary filmmakers

When Takeshi Kitano first rose to prominence as one half of comedy duo The Two Beats in the late 70s, few would have anticipated that 20 years later he would be one of his country’s leading film directors. Even as his films racked up awards at international film festivals in the mid-90s, few Japanese could take him seriously.

Already a household name by the 80s, ‘Beat’ Takeshi was so closely associated with comedy that his filmmaking “hobby” was largely dismissed until the watershed year of 1997. The provocative TV prankster was already the host of countless gameshows (Takeshi’s Castle, anyone?), the subject of a tabloid romance scandal, and even the face of a video game titled Takeshi’s Challenge before he even picked up a camera. But as an auteur – writing, directing and editing feature films in a show of singular creativity – Kitano almost instantaneously captured the imaginations of Western audiences.

A string of nihilistic crime dramas juxtaposing a contemplative filmmaking style with sudden violence would prove to be his most captivating works. And with the director occupying the lead acting role in each film, Kitano’s emotionless glare and hard-man persona would come to embody a whole new movement of Japanese cinema. The New Wave of the 90s would become so associated with Kitano that many critics would come to refer to it as “The ‘Beat’ Generation”.

As the BFI re-issues a trilogy of Kitano’s early works on Blu-ray as part of its ongoing Japan 2020 season, we consider five of the best features by one of 90s Japan’s most enduring directors.

1. Violent Cop, 1989

While Nagisa Ōshima had opened the door for Kitano’s acting career in 1983, casting him opposite David Bowie in Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence, it was another much-celebrated Japanese director who would pass the torch to Kitano for his directorial debut.

Kinji Fukasaku, famed for his gangster franchise Battles Without Honor or Humanity, had initially signed on to direct 1989’s Violent Cop with Kitano as lead actor. But when the veteran stepped away from the production, directorial duties were left to the film’s celebrity star. A decade later, Fukasaku would memorably cast Kitano as the antagonist schoolteacher of dystopian cult hit Battle Royale – but for now, Violent Cop was an opportunity for Kitano to show his chops as a director.

While gritty as hell, the film’s slow, ponderous camerawork and explosive moments of violence would elevate its simplistic plot enough to win it the Best Director prize at the Yokohama Film Festival. And while Kitano is largely dismissive of the film in retrospect (even suggesting that the lingering facial shots and extended walking scenes were included only to make up the film’s runtime) Violent Cop provides a thematic blueprint for the dichotomous crime films to come.

2. Sonatine, 1993

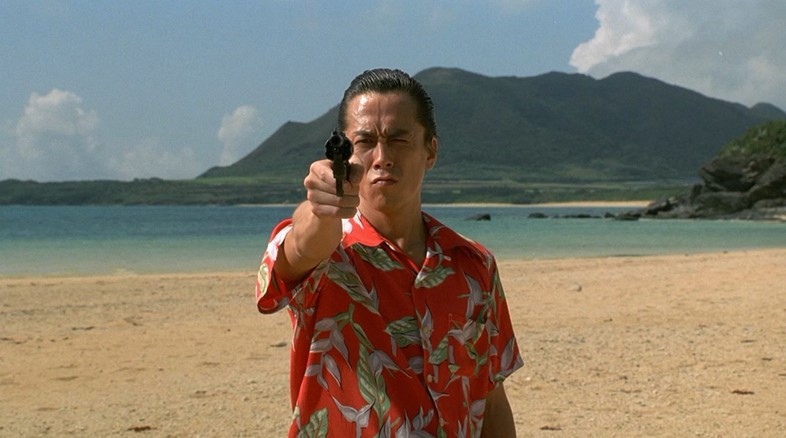

While the detached hard-man of Violent Cop is straightforwardly transposed onto disenchanted yakuza boss Murakawa in Sonatine, the film distinguishes itself from its predecessor through its sudden tonal shift in the second act. Ditching a grisly backdrop in Tokyo gangland, the cast of misfit thugs spend much of the film’s runtime on an idyllic beach paradise awaiting orders, in an unconventional subversion of the gangster genre’s established tropes.

While Kitano claims that the colourful beach vistas that often crop up in his films are a symbol of impending death, the most obvious effect of Sonatine’s peaceful central setting is that it completely disarms the viewer for the film’s violent conclusion.

For the most part, the film feels like a classic Yasujiro Ozu family drama – but the sad reality is that Murakama and his hoodlums are marked for death from the start. The bleak, Scarface-like conclusion ultimately feels inevitable, confirming that the euphoric fever dream shared in the film’s extended central act was but a fleeting taste of what life could have been.

3. Hana-bi, 1997

Like most of Kitano’s early works, Sonatine failed to find an audience at home – but after being picked up for the London Film Festival and nominated for the Best Director Award at Cannes, the director was beginning to make an impression abroad. Film composer Joe Hisaishi, best known for his whimsical scores to Studio Ghibli animations, had picked up a Japanese Academy Award for his score. And with regular actors Susumu Terajima (Ichi The Killer), and Ren Osugi (Cure) now forming a recognisable cast of faces in Kitano’s universe, the director was poised for a breakthrough.

The culmination of all Kitano’s filmmaking experience came in 1997, one of the most significant years in Japanese film history. As Naomi Kawase and Shoehei Imamura received major honours at Cannes (for Suzaku and Unagi/The Eel respectively), Kitano’s Hana-bi completed an unlikely triplicate when it won Japan the Golden Lion at Venice. It was only the second Japanese film to win top honours since Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon won the award in 1950.

This elegiac masterwork marked Kitano’s return to the crime genre as writer-actor-director after a major traffic accident had almost cost him his life. As Nishi, a laconic police detective haunted by the shootings of two close colleagues and caring for a cancer-stricken wife, Kitano’s pensive performance is delivered with remarkable emotional weight. The punch at the film’s climax would prove heavy enough to finally win over his native audience – and from here on, the TV comedian would be regarded in the upper echelons of film criticism the world over.

4. Brother, 2000

When Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence producer Jeremy Thomas came knocking to offer Kitano a Hollywood-based feature of his own in 2000, the director lapped up the opportunity on the condition that he could retain full creative control. The resulting film, Brother, remains something of an oddity in his back catalogue. To this day his only feature made outside of Japan, it follows Kitano’s archetypal, introverted gangster as he builds an empire in the unfamiliar setting of Los Angeles.

Rather than attempt to adapt his filmmaking craft to the Hollywood mould, Brother merely swaps Tokyo for LA and throws in a few American actors as an attempt to capitalise on the newfound popularity of Japanese cinema abroad. Kitano’s legendary lack of patience feels like it’s on full show here. While his economical shooting style had captured moments of magic so often before, the scant rehearsals and one-take filming are less conducive with Brother’s B-movie cast and clunky script.

But despite its shortcomings, Brother is a fascinatingly surreal piece of work; a unique example of a steadfastly Japanese film made on American soil. Styled by Yohji Yamamoto, chock-full of black humour, and lined with a colourful blend of pinky choppings, hara-kiri and chopstick assaults, it places everything that makes Kitano so engrossing in unfamiliar territory. There are some meditative moments amid the many beatings, too, with one elliptical sequence of a paper airplane floating through downtown LA to the sound of Hisaishi’s rousing score providing a gentle highlight.

5. Outrage, 2010

“The days are over for old-school yakuza” utters one player in this long-overdue entry that would return Kitano to the gangster genre for the first time in a decade. The phrase rings true for the director himself. While seen by many as a return to form, Outrage presents a stylistic departure from the more poetic works that had coloured the director’s reputation in the 90s.

Having scored a hit to the tune of $23.8 million with his 2003 reboot of Zatoichi, a long-running franchise about a blind swordsman, Kitano was bent on creating another blockbuster. He was modestly successful. After competing for the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2010, Outrage brought home $8.5 million in worldwide box office sales, and spawned two lucrative sequels.

Modelled more on Western gangster films than his previous works, Outrage sheds much of the idiosyncratic tropes of Kitano’s earlier works – but for a glossy and slick crime epic, it ticks all the boxes. It sees the return of Kitano’s stoic hard-man as a yakuza lieutenant caught in a war of families and features a multitude of violent slayings as its cornerstones. With some outstanding performances by genre heavyweights Jun Kunimura (Kill Bill) and Renji Ishibashi (Audition), this Japanese Godfather is extremely satisfying, if not a little conventional.

The Takeshi Kitano Collection is out now. Explore the BFI’s Japan 2020 season here.