“A photograph is a secret about a secret, the more it tells you, the less you know” – Diane Arbus

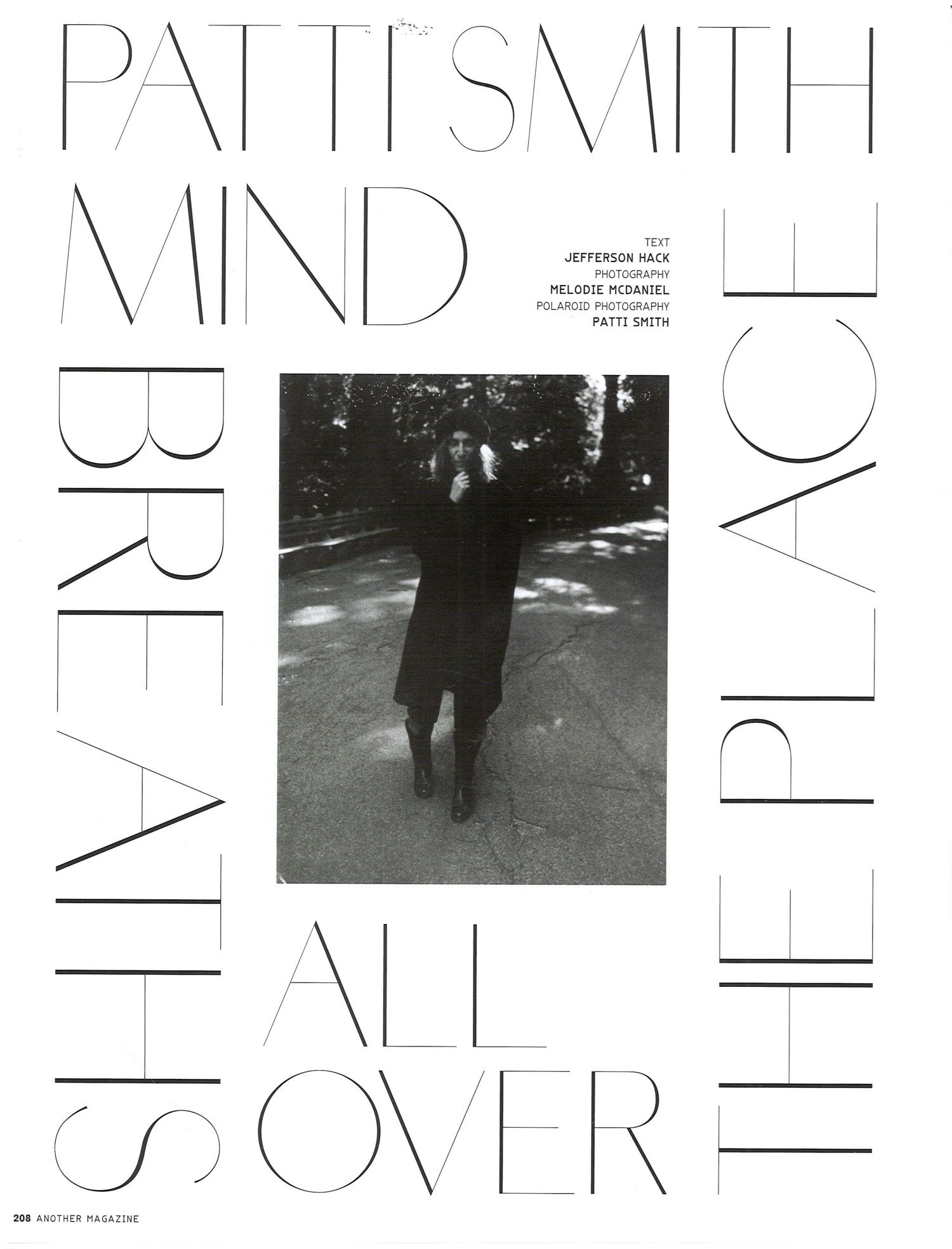

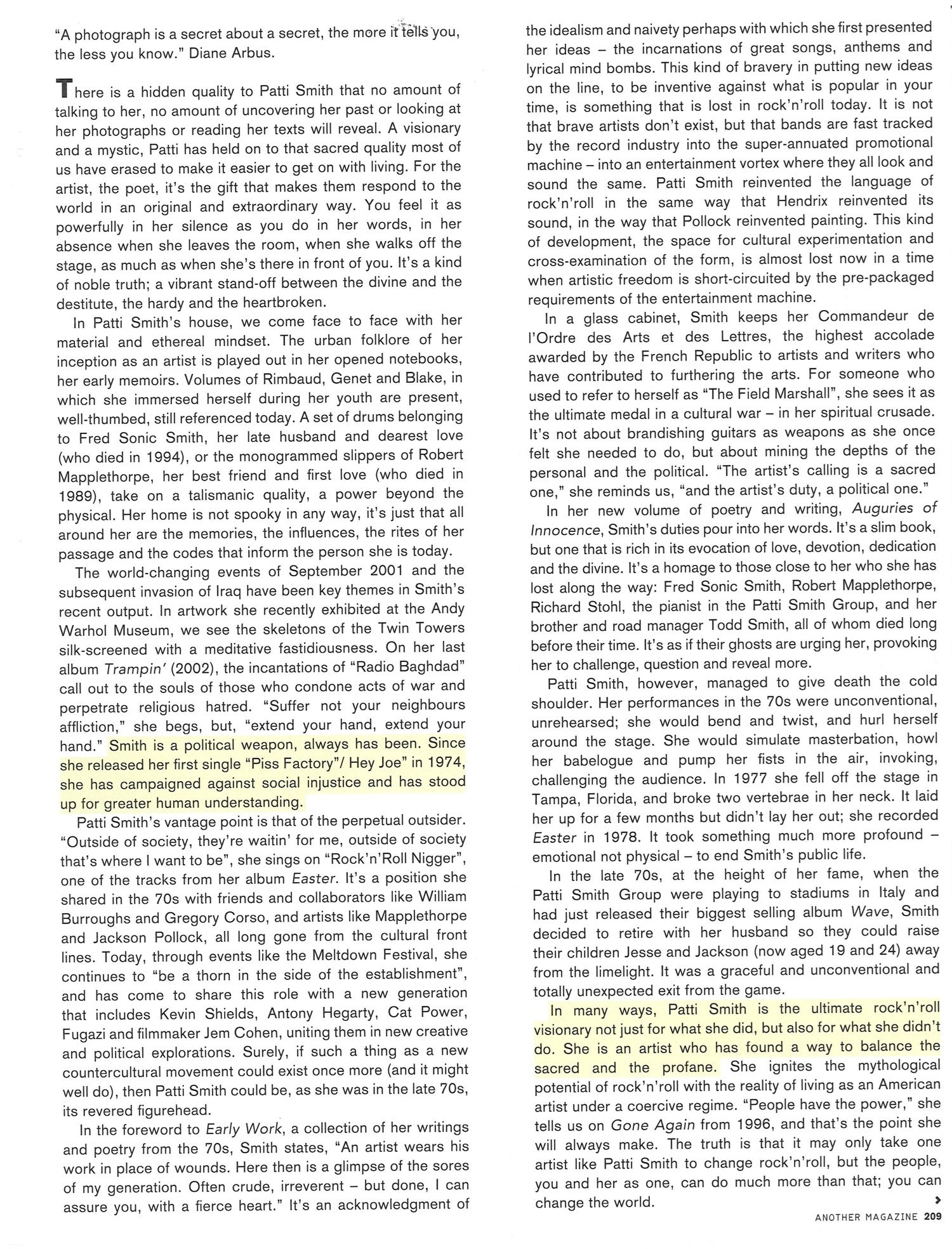

There is a hidden quality to Patti Smith that no amount of talking to her, no amount of uncovering her past or looking at her photographs or reading her texts will reveal. A visionary and a mystic, Patti has held on to that sacred quality most of us have erased to make it easier to get on with living. For the artist, the poet, it’s the gift that makes them respond to the world in an original and extraordinary way. You feel it as powerfully in her silence as you do in her words, in her absence when she leaves the room, when she walks off the stage, as much as when she’s there in front of you. It’s a kind of noble truth; a vibrant stand-off between the divine and the destitute, the hardy and the heartbroken.

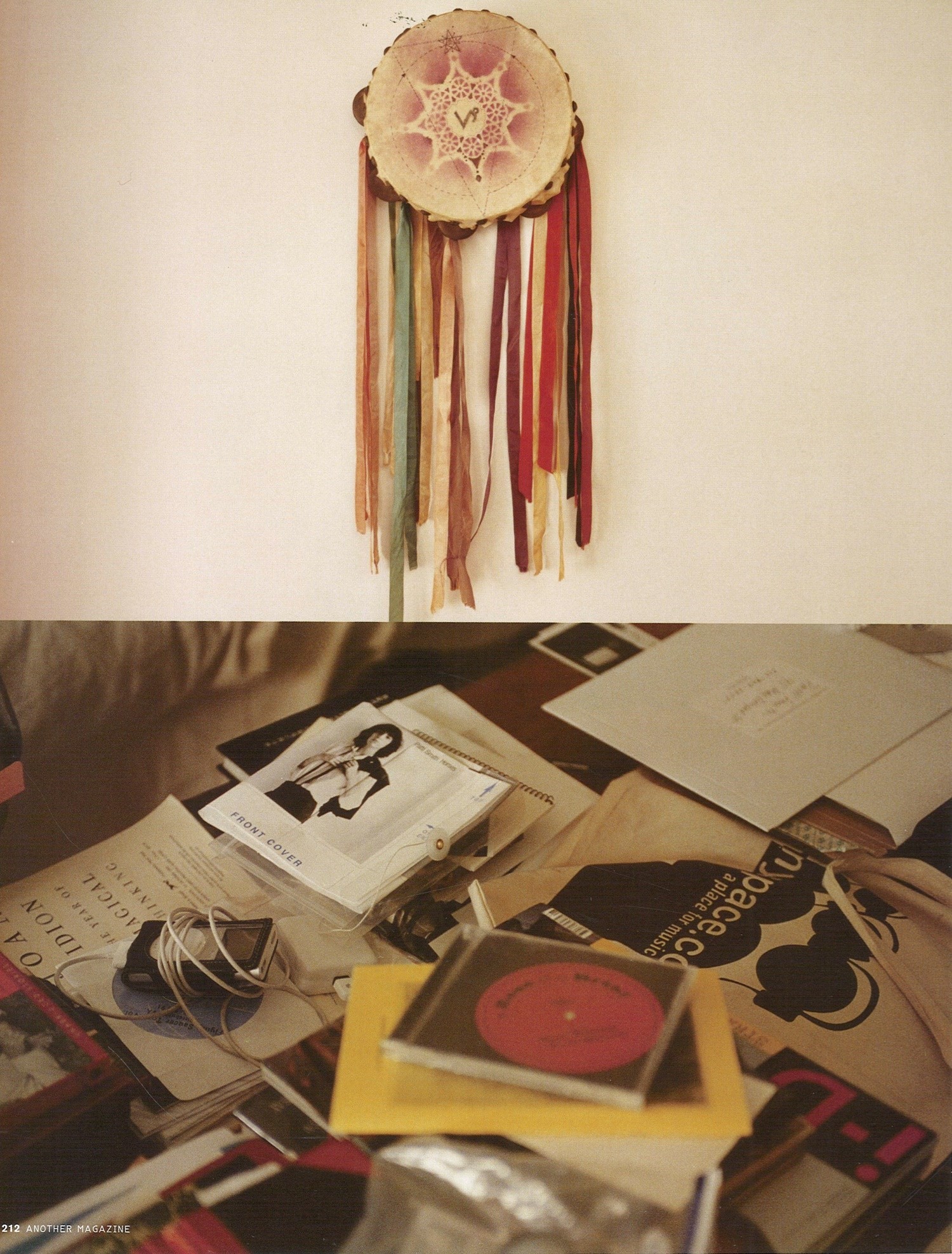

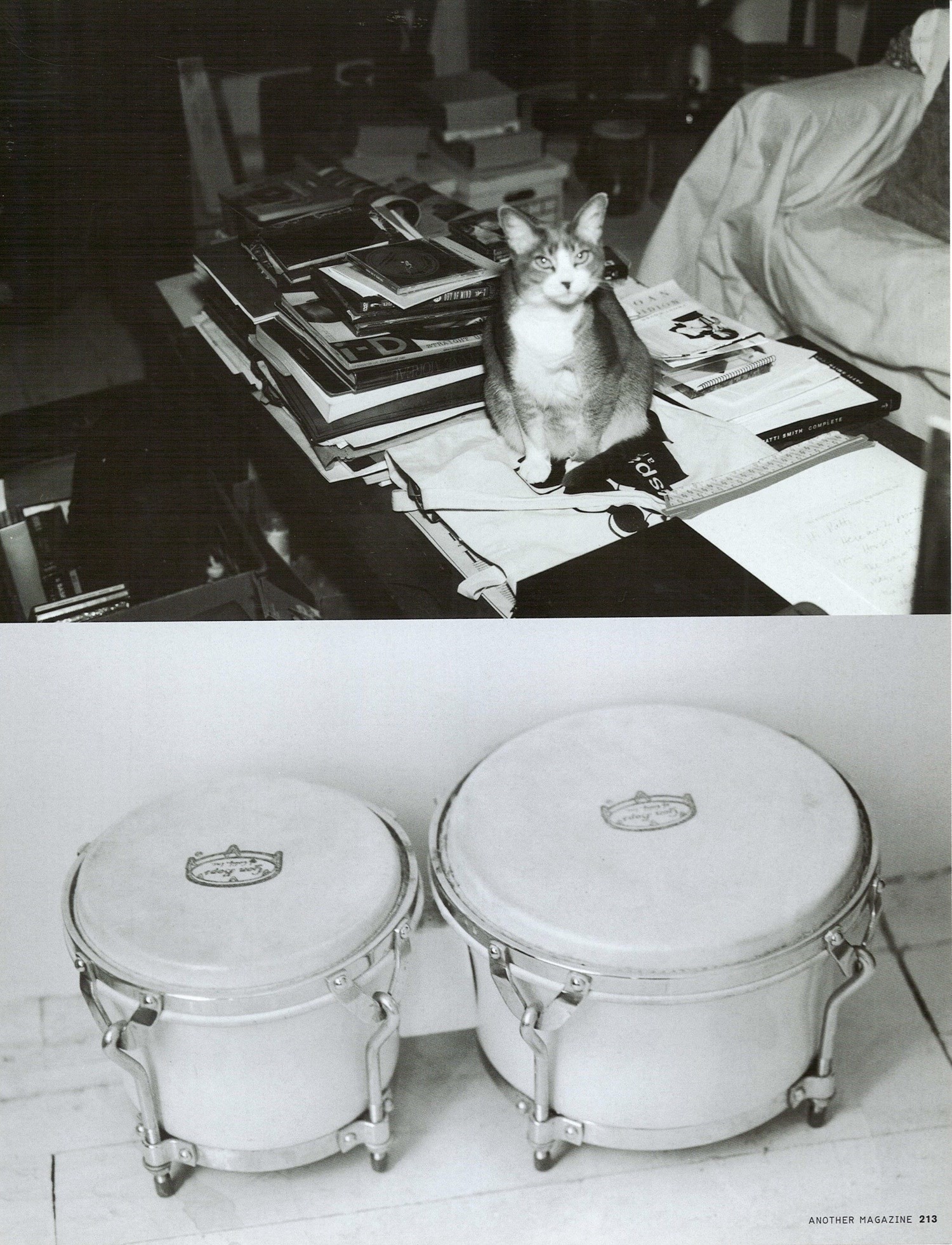

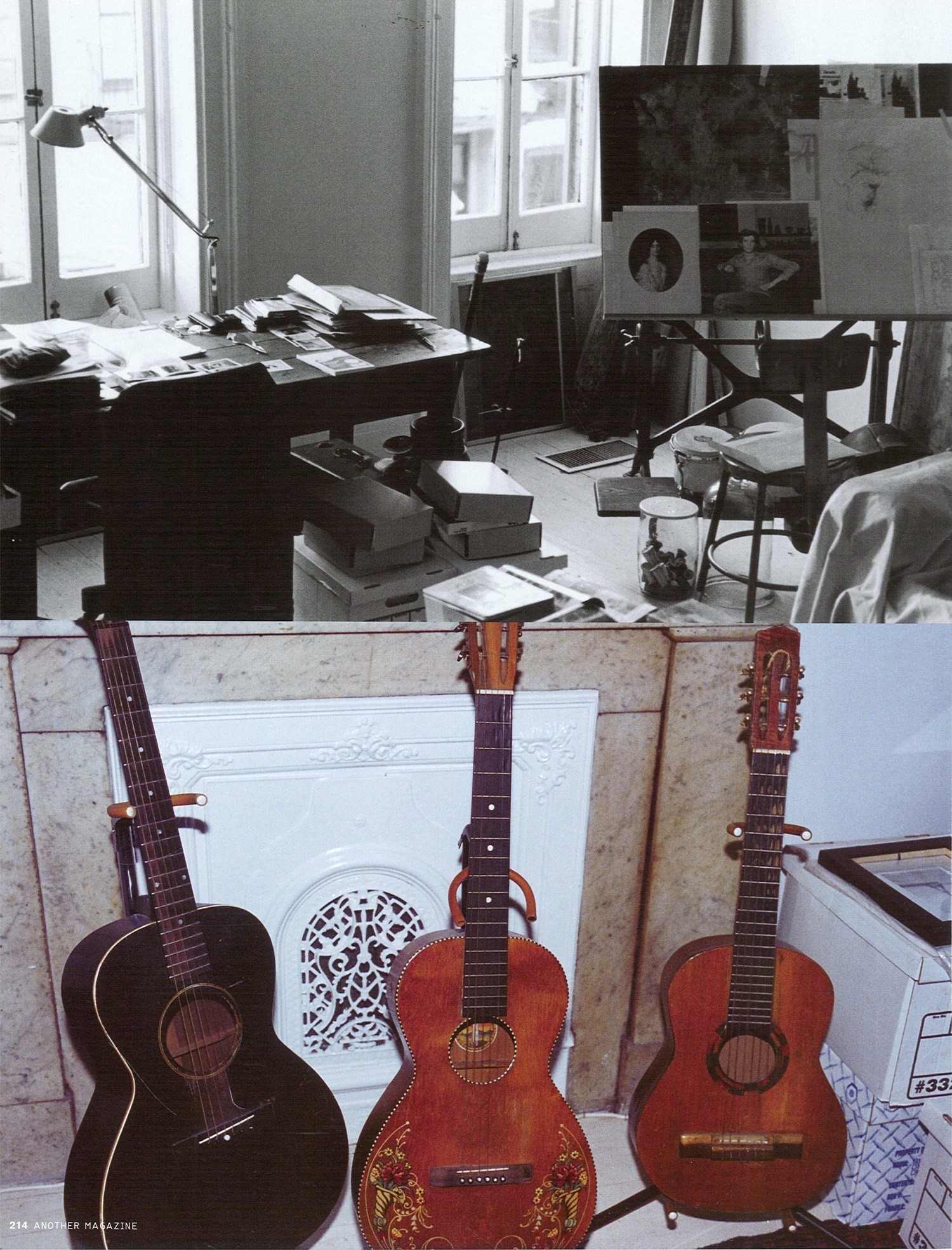

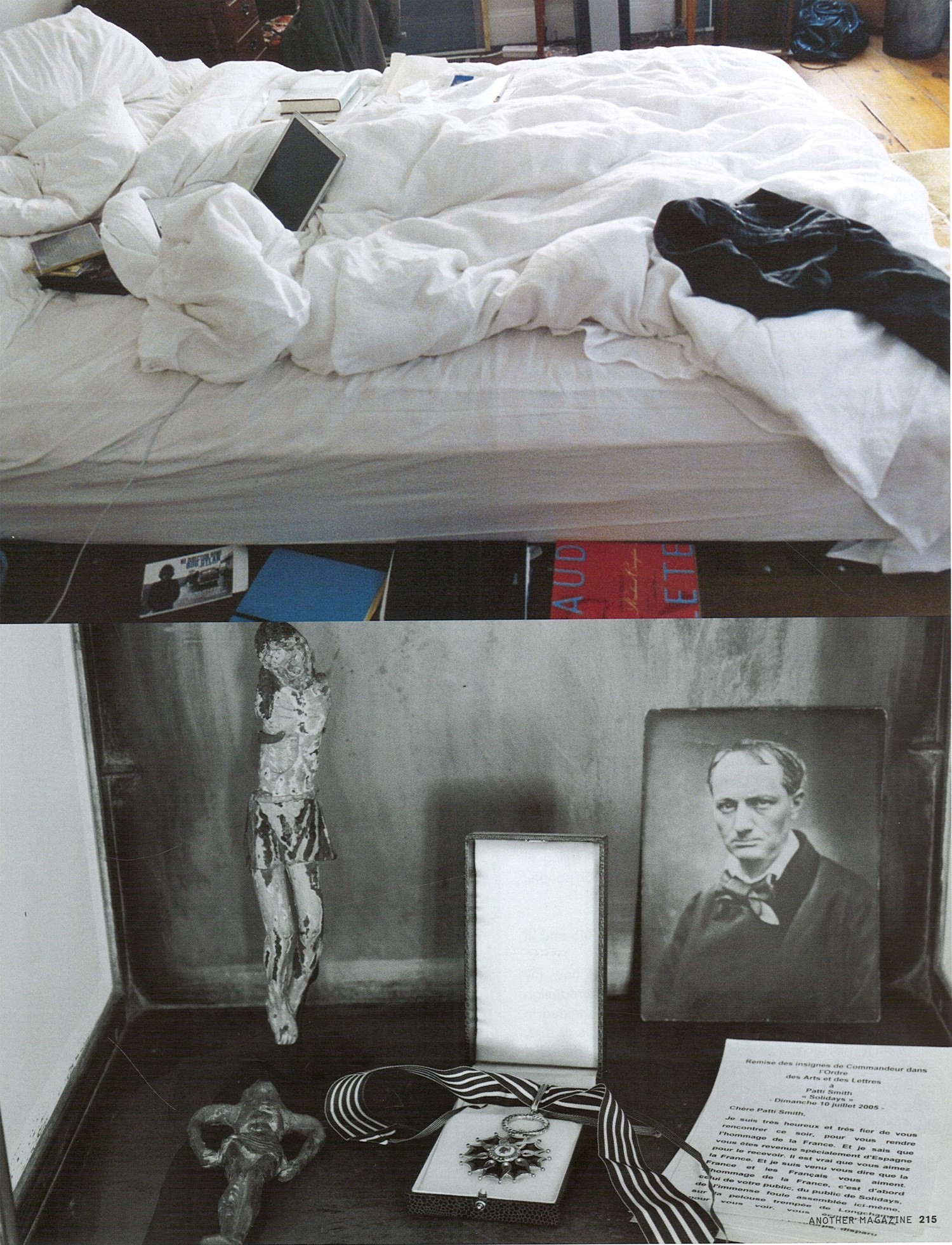

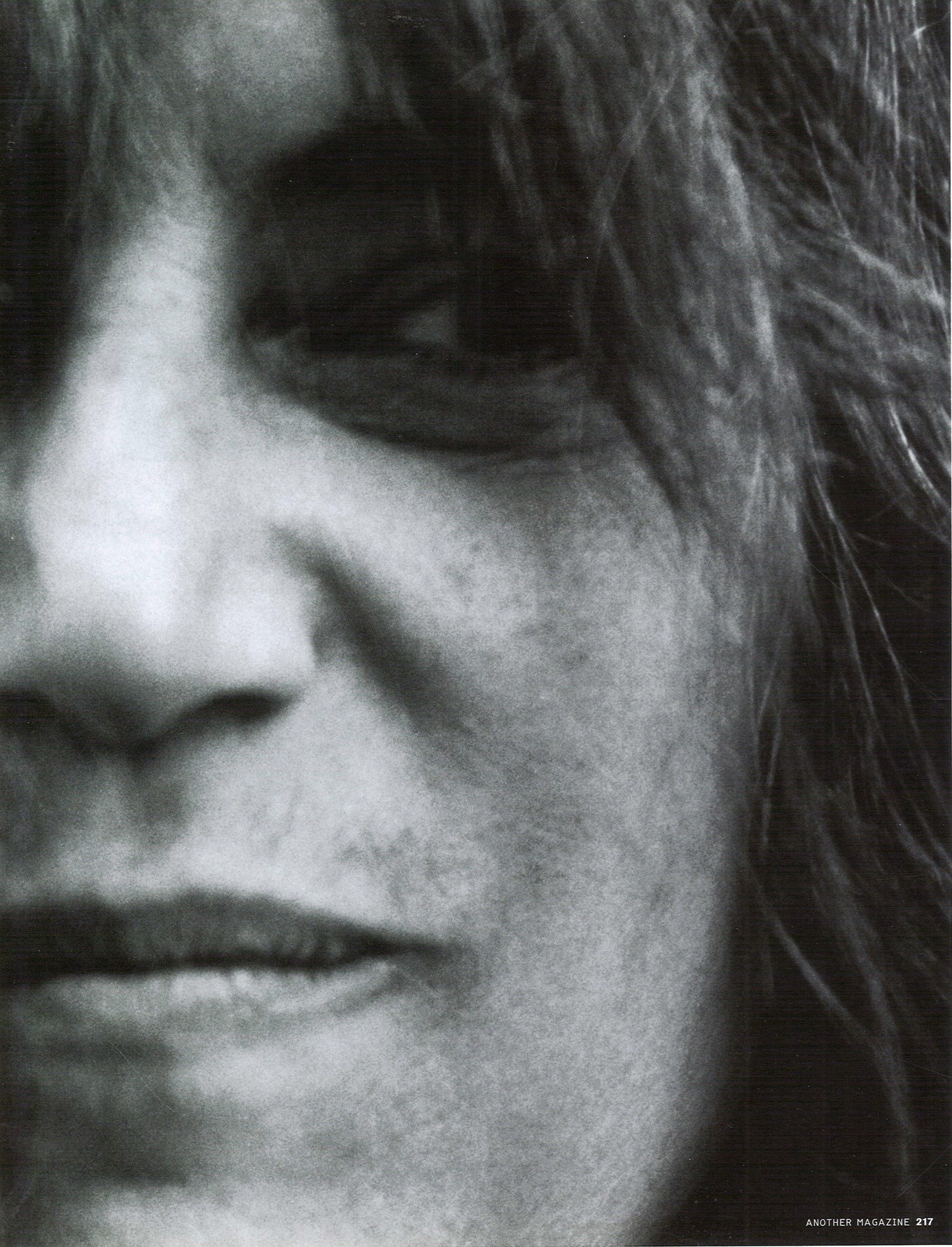

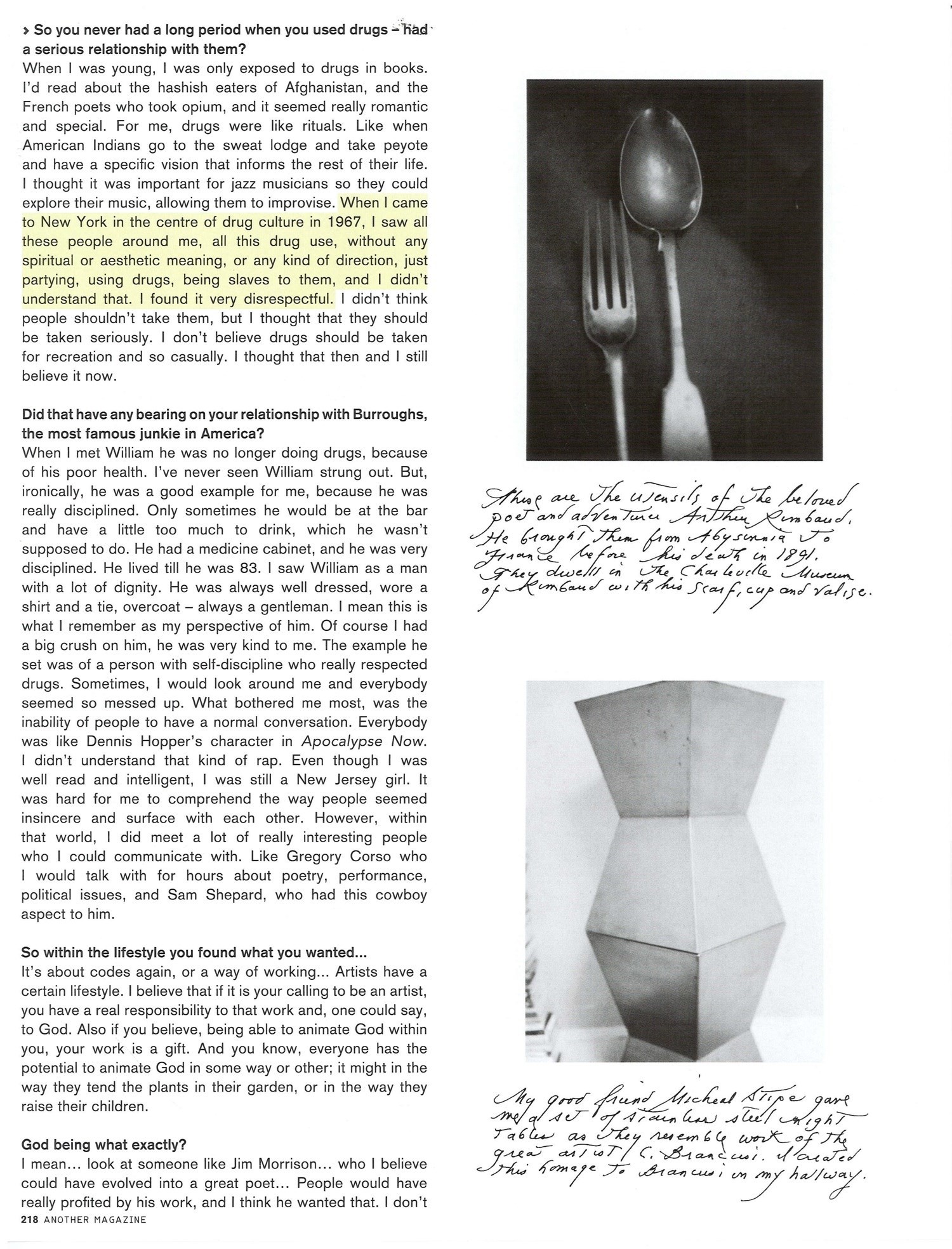

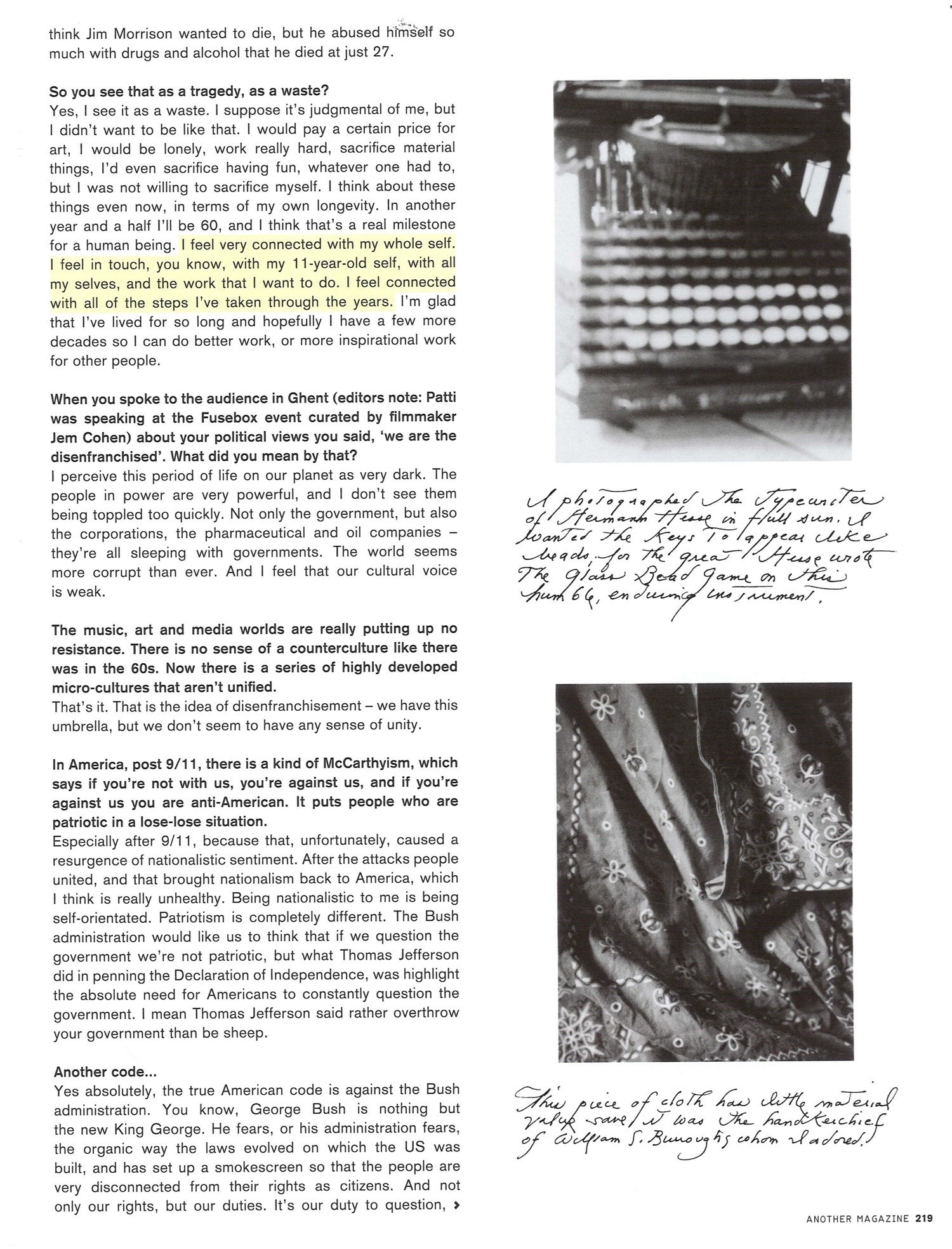

In Patti Smith’s house, we come face to face with her material and ethereal mindset. The urban folklore of her inception as an artist is played out in her opened notebooks, her early memoirs. Volumes of Rimbaud, Genet and Slake, in which she immersed herself during her youth are present, well-thumbed, still referenced today. A set of drums belonging to Fred Sonic Smith, her late husband and dearest love (who died in 1994), or the monogrammed slippers of Robert Mapplethorpe, her best friend and first love (who died in 1989), take on a talismanic quality, a power beyond the physical. Her home is not spooky in any way, it’s just that all around her are the memories, the influences, the rites of her passage and the codes that inform the person she is today.

The world-changing events of September 2001 and the subsequent invasion of Iraq have been key themes in Smith’s recent output. In artwork she recently exhibited at the Andy Warhol Museum, we see the skeletons of the Twin Towers silk-screened with a meditative fastidiousness. On her last album Trampin’ (2002), the incantations of Radio Baghdad call out to the souls of those who condone acts of war and perpetrate religious hatred. “Suffer not your neighbours affliction,” she begs, but, “extend your hand, extend your hand.” Smith is a political weapon, always has been. Since she released her first single Piss Factory / Hey Joe in 1974, she has campaigned against social injustice and has stood up for greater human understanding.

Patti Smith’s vantage point is that of the perpetual outsider. “Outside of society, they’re waitin’ for me, outside of society that’s where I want to be,” she sings on Rock’n’Roll Nigger, one of the tracks from her album Easter. It’s a position she shared in the 70s with friends and collaborators like William Burroughs and Gregory Corso, and artists like Mapplethorpe and Jackson Pollock, all long gone from the cultural front lines. Today, through events like the Meltdown Festival, she continues to “be a thorn in the side of the establishment”, and has come to share this role with a new generation that includes Kevin Shields, Antony Hegarty, Cat Power, Fugazi and filmmaker Jem Cohen, uniting them in new creative and political explorations. Surely, if such a thing as a new countercultural movement could exist once more (and it might well do), then Patti Smith could be, as she was in the late 70s, its revered figurehead.

In the foreword to Early Work, a collection of her writings and poetry from the 70s, Smith states, “An artist wears his work in place of wounds. Here then is a glimpse of the sores of my generation. Often crude, irreverent – but done, I can assure you, with a fierce heart.” It’s an acknowledgment of the idealism and naivety perhaps with which she first presented her ideas – the incarnations of great songs, anthems and lyrical mind bombs. This kind of bravery in putting new ideas on the line, to be inventive against what is popular in your time, is something that is lost in rock’n’roll today. It is not that brave artists don’t exist, but that bands are fast tracked by the record industry into the super-annuated promotional machine – into an entertainment vortex where they all look and sound the same. Patti Smith reinvented the language of rock’n’roll in the same way that Hendrix reinvented its sound, in the way that Pollock reinvented painting. This kind of development, the space for cultural experimentation and cross-examination of the form, is almost lost now in a time when artistic freedom is short-circuited by the pre-packaged requirements of the entertainment machine.

In a glass cabinet, Smith keeps her Commandeur de I’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, the highest accolade awarded by the French Republic to artists and writers who have contributed to furthering the arts. For someone who used to refer to herself as “The Field Marshall”, she sees it as the ultimate medal in a cultural war – in her spiritual crusade. it’s not about brandishing guitars as weapons as she once felt she needed to do, but about mining the depths of the personal and the political. “The artist’s calling is a sacred one,” she reminds us, “and the artist’s duty, a political one”.

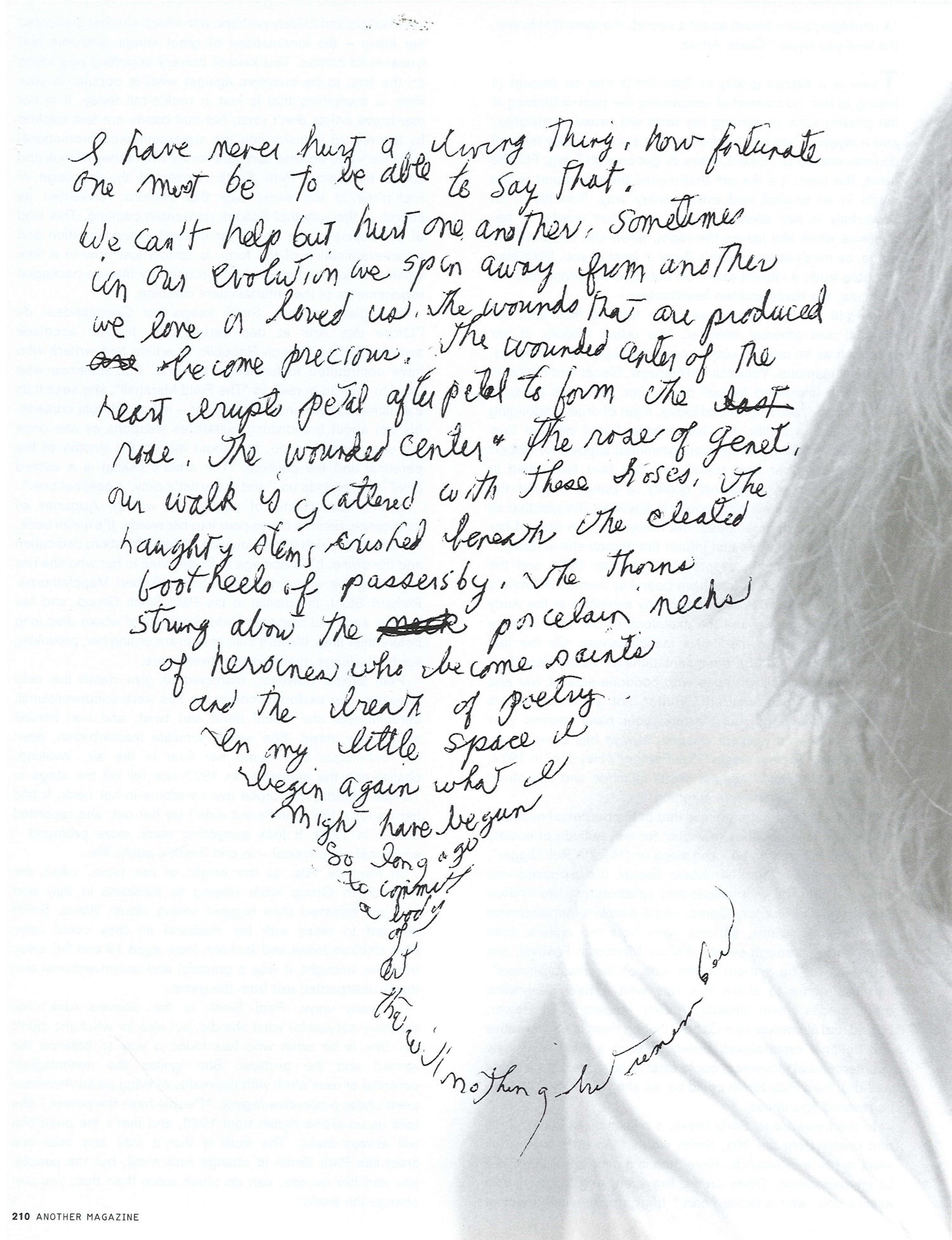

In her new volume of poetry and writing, Auguries of Innocence, Smith’s duties pour into her words. It’s a slim book, but one that is rich in its evocation of love, devotion, dedication and the divine. It’s a homage to those close to her who she has lost along the way: Fred Sonic Smith, Robert Mapplethorpe, Richard Stohl, the pianist in the Patti Smith Group, and her brother and road manager Todd Smith, all of whom died long before their time. It’s as if their ghosts are urging her, provoking her to challenge, question and reveal more.

Patti Smith, however, managed to give death the cold shoulder. Her performances in the 70s were unconventional, unrehearsed; she would bend and twist, and hurl herself around the stage. She would simulate masterbation, howl her babelogue and pump her fists in the air, invoking, challenging the audience. In 1977 she fell off the stage in Tampa, Florida, and broke two vertebrae in her neck. It laid her up for a few months but didn’t lay her out; she recorded Easter in 1978. It took something much more profound – emotional not physical – to end Smith’s public life.

In the late 70s, at the height of her fame, when the Patti Smith Group were playing to stadiums in Italy and had just released their biggest selling album Wave, Smith decided to retire with her husband so they could raise their children Jesse and Jackson (now aged 19 and 24) away from the limelight. It was a graceful and unconventional and totally unexpected exit from the game.

In many ways, Patti Smith is the ultimate rock’n’roll visionary not just for what she did, but also for what she didn’t do. She is an artist who has found a way to balance the sacred and the profane. She ignites the mythological potential of rock’n’roll with the reality of living as an American artist under a coercive regime. “People have the power,” she tells us on Gone Again from 1996, and that’s the point she will always make. The truth is that it may only take one artist like Patti Smith to change rock’n’roll, but the people, you and her as one, can do much more than that; you can change the world.

Jefferson Hack: You’re performing a lot at the moment. Are you enjoying it?

Patti Smith: Yes immensely. When I was younger I didn’t know so much about performing, it was all intuitive. I didn’t train to be a singer or a musician, I just did it. And I was pretty fearless.

JH: Were you surprised by how much of a physical performer you could be?

PS: Yeah, I was always shocked at how aggressive I was, because normally I’m pretty even tempered. But I have these feelings in me, because there is so much injustice in the world, that I can’t help feeling a certain amount of rage. Performance has always been a way for me to channel that rage. lt’s been a very good vehicle.

JH: How did it feel to play the entire Horses album at the Meltdown festival last year?

PS: That was one of those nights when the people really ruled. They were really electric and I could feel their energy – it was a beautiful thing. We recorded the show, but I felt like somehow, if I could have captured the audience and recorded them, it would have made it great, not because they were cheering and clapping, but because there was an electricity in the air that was really fantastic. Our bass player mixed the recording for the anniversary CD and he brought Gioria round, and we sat in the car and listened. lt made me cry. lt had a real spirit. Sometimes you attempt things like that but you don’t know if they’re really going to come across well, but I was happy with it. I felt like the spirit of that night wasn’t that different to the early years. For me, Gioria was a declaration of existence. What I’m trying to say is that we weren’t just going through the motions. I felt like that authenticity came through.

JH: Do you feel as creatively powerful, as free in your expression as you did when you wrote Horses?

PS: Well hopefully I feel more powerful. Even though I’m older I still feel that I haven’t accomplished all of the things I want to, nor have I reached the place I want to get to, so I’m still struggling and working, just like I always did. In that way, I’m connected with all of my selves. I don’t feel like somebody who produced a bunch of genius work at one point and now I’m in my declining years. I feel like I’m still trying to communicate something through a song that will touch people. I’m still working on things.

JH: Do you think that you have certain codes in your life and in your work?

PS: When I was younger, I didn’t really think about how my actions or work would affect people – how it might redesign their thinking. Or if I hurt somebody, how that resonated in their life. So I am really trying to be more conscious of that, and I think that a lack of codes or having certain personal standards just leads to a murky chaos. Not an exciting anarchy or anything, just people hurting each other, people getting sick. I think it’s important to have that. I learnt a lot when I lived in the Chelsea Hotel in the 60s. I would see people spinning out of control all over the place. Some died, some committed suicide, some got so disconnected from reality that they could no longer work or form a sentence straight. I certainly didn’t want to get like that.

JH: So you never had a long period when you used drugs – had a serious relationship with them?

PS: When I was young, I was only exposed to drugs in books. I’d read about the hashish eaters of Afghanistan, and the French poets who took opium, and it seemed really romantic and special. For me, drugs were like rituals. Like when American Indians go to the sweat lodge and take peyote and have a specific vision that informs the rest of their life. I thought it was important for jazz musicians so they could explore their music, allowing them to improvise. When I came to New York in the centre of drug culture in 1967, I saw all these people around me, all this drug use, without any spiritual or aesthetic meaning, or any kind of direction, just partying, using drugs, being slaves to them, and I didn’t understand that. I found it very disrespectful. I didn’t think people shouldn’t take them, but I thought that they should be taken seriously. I don’t believe drugs should be taken for recreation and so casually. I thought that then and I still believe it now.

JH: Did that have any bearing on your relationship with Burroughs, the most famous junkie in America?

PS: When I met William he was no longer doing drugs, because of his poor health. I’ve never seen William strung out. But, ironically, he was a good example for me, because he was really disciplined. Only sometimes he would be at the bar and have a little too much to drink, which he wasn’t supposed to do. He had a medicine cabinet, and he was very disciplined. He lived till he was 83. I saw William as a man with a lot of dignity. He was always well dressed, wore a shirt and a tie, overcoat – always a gentleman. I mean this is what I remember as my perspective of him. Of course I had a big crush on him, he was very kind to me. The example he set was of a person with self-discipline who really respected drugs. Sometimes, I would look around me and everybody seemed so messed up. What bothered me most, was the inability of people to have a normal conversation. Everybody was like Dennis Hopper’s character in Apocalypse Now. I didn’t understand that kind of rap. Even though I was well read and intelligent, I was still a New Jersey girl. lt was hard for me to comprehend the way people seemed insincere and surface with each other. However, within that world, I did meet a lot of really interesting people who I could communicate with. Like Gregory Corso who I would talk with for hours about poetry, performance, political issues, and Sam Shepard, who had this cowboy aspect to him.

JH: So within the lifestyle you found what you wanted …

PS: It’s about codes again, or a way of working ... Artists have a certain lifestyle. I believe that if it is your calling to be an artist, you have a real responsibility to that work and, one could say, to God. Also if you believe, being able to animate God within you, your work is a gift. And you know, everyone has the potential to animate God in some way or other; it might in the way they tend the plants in their garden, or in the way they raise their children.

JH: God being what exactly?

PS: I mean ... look at someone like Jim Morrison ... who I believe could have evolved into a great poet ... People would have really profited by his work, and I think he wanted that. I don’t think Jim Morrison wanted to die, but he abused himself so much with drugs and alcohol that he died at just 27.

JH: So you see that as a tragedy, as a waste?

PS: Yes, I see it as a waste. I suppose it’s judgmental of me, but I didn’t want to be like that. I would pay a certain price for art, I would be lonely, work really hard, sacrifice material things, I’d even sacrifice having fun, whatever one had to, but I was not willing to sacrifice myself. I think about these things even now, in terms of my own longevity. In another year and a half I’ll be 60, and I think that’s a real milestone for a human being. I feel very connected with my whole self. I feel in touch, you know, with my 11-year-old self, with all my selves, and the work that I want to do. I feel connected with all of the steps I’ve taken through the years. I’m glad that I’ve lived for so long and hopefully I have a few more decades so I can do better work, or more inspirational work for other people.

JH: When you spoke to the audience in Ghent (editor’s note: Patti was speaking at the Fusebox event curated by filmmaker Jem Cohen) about your political views you said, ‘we are the disenfranchised’. What did you mean by that?

PS: I perceive this period of life on our planet as very dark. The people in power are very powerful, and I don’t see them being toppled too quickly. Not only the government, but also the corporations, the pharmaceutical and oil companies – they’re all sleeping with governments. The world seems more corrupt than ever. And I feel that our cultural voice is weak.

JH: The music, art and media worlds are really putting up no resistance. There is no sense of a counterculture like there was in the 60s. Now there is a series of highly developed micro-cultures that aren’t unified.

PS: That’s it. That is the idea of disenfranchisement – we have this umbrella, but we don’t seem to have any sense of unity.

JH: In America, post 9/11, there is a kind of McCarthyism, which says if you’re not with us, you’re against us, and if you’re against us you are anti-American. lt puts people who are patriotic in a lose-lose situation.

PS: Especially after 9/11, because that, unfortunately, caused a resurgence of nationalistic sentiment. After the attacks people united, and that brought nationalism back to America, which I think is really unhealthy. Being nationalistic to me is being self-orientated. Patriotism is completely different. The Bush administration would like us to think that if we question the government we’re not patriotic, but what Thomas Jefferson did in penning the Declaration of Independence, was highlight the absolute need for Americans to constantly question the government. I mean Thomas Jefferson said rather overthrow your government than be sheep.

JH: Another code …

PS: Yes absolutely, the true American code is against the Bush administration. You know, George Bush is nothing but the new King George. He fears, or his administration fears, the organic way the laws evolved on which the US was built, and has set up a smokescreen so that the people are very disconnected from their rights as citizens. And not only our rights, but our duties. It’s our duty to question, it’s certainly the media’s duty to question and I think they have failed completely and betrayed us. They failed and betrayed us in their reporting of the Iraq occupation, and they’re failing us now. And that’s why I talk about being disenfranchised. I was heartbroken when the Bush administration said they were going to invade Iraq. I couldn’t believe that the people would let them do that. I couldn’t believe that the Democratic Party would support him in giving him the power to do that. We were betrayed down the line. So, again, where are our examples today? The Democratic Party has, since I was a child, been the torchbearer for doing the right thing.

JH: Not supporting the war and wanting a change of government are two different things. That’s the danger of having a two-party system, they become so closely aligned. Kicking out the reds and getting in the blues doesn’t necessarily work.

PS: That whole colours thing is bullshit – that polarisation of people. During the Vietnam war, the red and the blue didn’t mean shit to the 50,000 parents who lost their sons. Suddenly nobody cared if they were Democrat or Republican, it didn’t matter. People wanted the war to end because their children were dying. It was a huge emotional and physical drain on our country – the guilt and confusion, all the death. 50,000 Americans died, but hundreds of thousands were maimed or psychologically damaged, and so the nation had a strong, unified voice against it. When we protested against the Iraq war, 150,000 people gathered in Washington, and Jesse Jackson spoke, along with various other strong speakers, but it was never reported. The press gave us a small paragraph somewhere. I had five different interviews set up with CNN, but they cancelled every one of them. I realised that the only way you can influence political change in America is for huge numbers to come forth, and I don’t see that happening right now. So what I feel is that we who believe, and are not heard, and have no real voice or real power, because of our media, have to find each other and unite. And I think that is really important. We can’t become depressed or feel ineffectual, we have to start building a counterculture, a new underground, and just do our work.

JH: Like your heroes, Rimbaud and Blake?

PS: I always come back to William Blake because in his time, he saw so much injustice, saw women being beaten to a pulp in the street, 11-year-olds as prostitutes, toddlers as chimney sweeps, children in the mills working through the night with no food. He just walked the streets, and saw such rampant human degradation, and was so moved by it, that he tried to make changes. He tried to join political movements, but they were so disorganised that he had to withdraw. He spoke out and was nearly hanged for dissent, and so finally he did the best thing that he could: he worked. And he spoke about issues and offered new possibilities, or laid out the horrific situation children were put in. People didn’t listen in his lifetime, but future generations did. And now, William Blake’s work and thoughts inform our culture. So I don’t have an ‘if you can’t beat them join them’ philosophy, but I also don’t have the ‘if you can’t beat them, curl up in a ball’ philosophy. If you can’t beat them, just do your work. And as I like to put it, it becomes a thorn in their side – just keep pricking them and pricking them and pricking them until they bleed.

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2006 issue of AnOther Magazine.