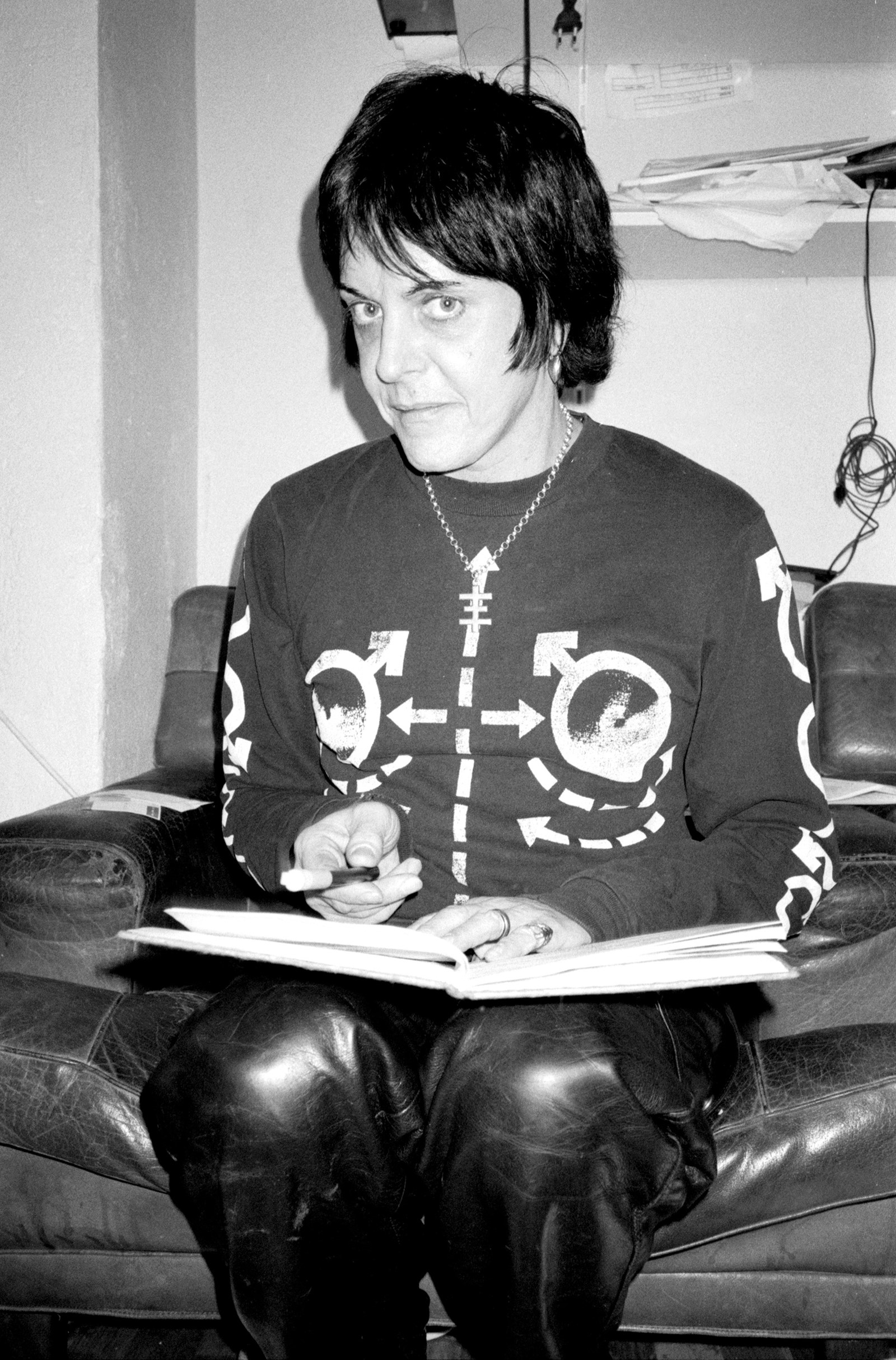

The British artist Genesis Breyer P-Orridge first rose to prominence in the 1970s as the founding member of C.O.U.M. Transmissions, a performance art collective whose 1976 exhibition Prostitution at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London – which involved visceral installations and performances exploring sex, the body and pornography – saw them memorably deemed by the Tory MP Nicholas Fairbairn as “wreckers of Western civilisation”. The moniker would, ironically, prove fitting: until P-Orridge’s death earlier this year aged 70, following a battle with leukaemia, their work across media was continually fixated with the destruction of societal boundaries, attempting to dismantle and transgress the hegemonic power structures of those in control. “I am at war with the status quo of society and I am at war with those in control and power,” they said in 1989.

As part of the band Throbbing Gristle, founded in the 1970s – which pioneered industrial music as we know it today – P-Orridge’s lyrics, repeated over abrasive machine-like rhythms, spoke of child murder, the Holocaust and the arms trade; after Gristle, in the 1980s, P-Orridge founded the band Psychic TV, which sought to harness what they believed was television’s power for mass mind control, cementing P-Orridge’s position as an ‘anti-musician’. “Psychic TV is a video group who does music unlike a music group which makes music videos,” P-Orridge once described the project, which came with its own occult offshoot, Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth.

But it was their transgressions of the gendered body for which P-Orridge would latterly become known: after meeting their second wife, Lady Jaye, in a BDSM dungeon in New York, the pair began the Pandrogeny Project, in which they undertook body modification to become the mirror image of one another, beginning with matching breast implants on Valentine’s Day in 2003. When they were together, they referred to themselves as a third person – Breyer P-Orridge – who only existed when they were together, and was referred to with the pronoun “we”, which P-Orridge continued to use after Lady Jaye died in 2007 as tribute (P-Orridge also added Breyer to their name full-time).

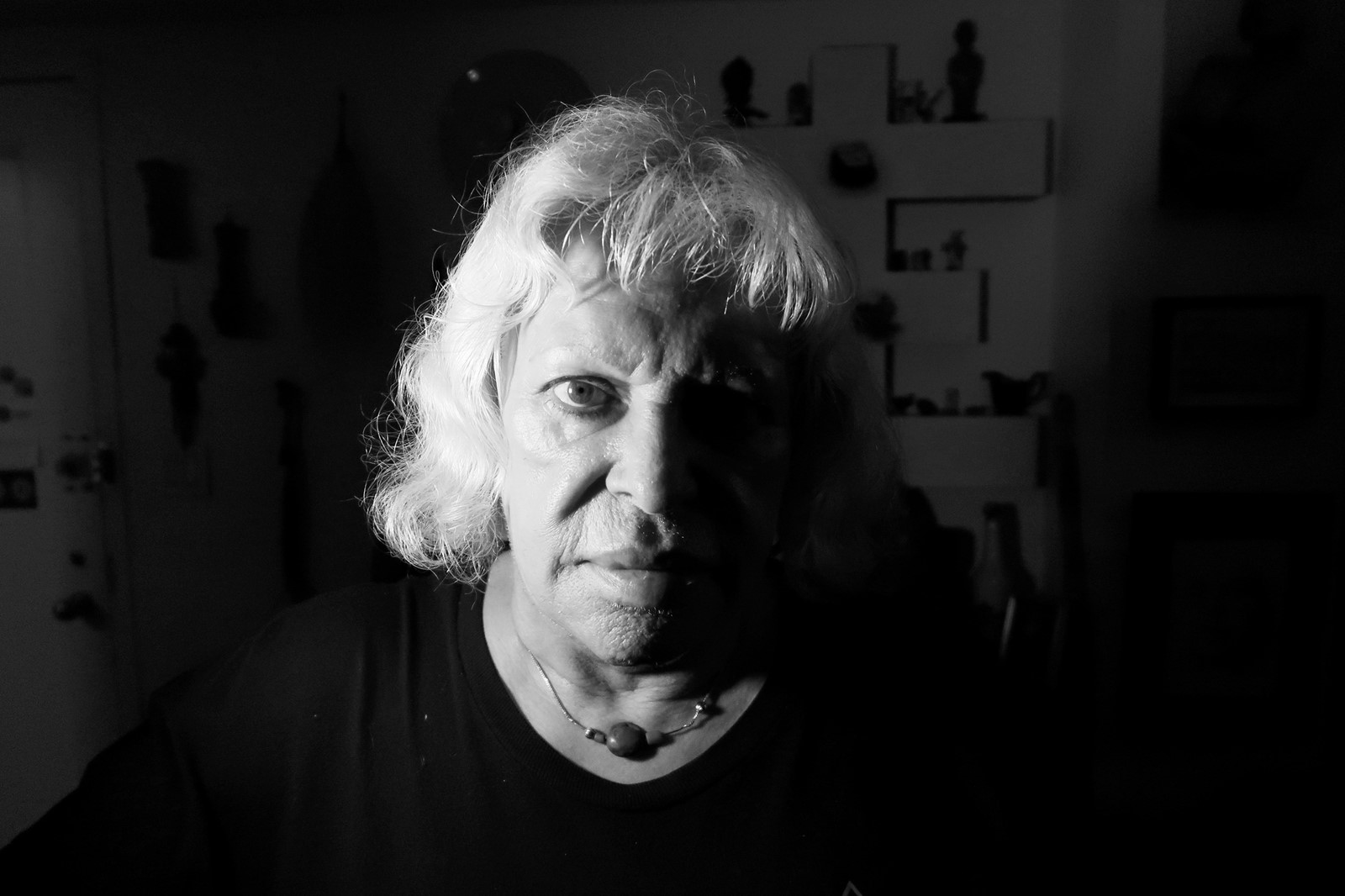

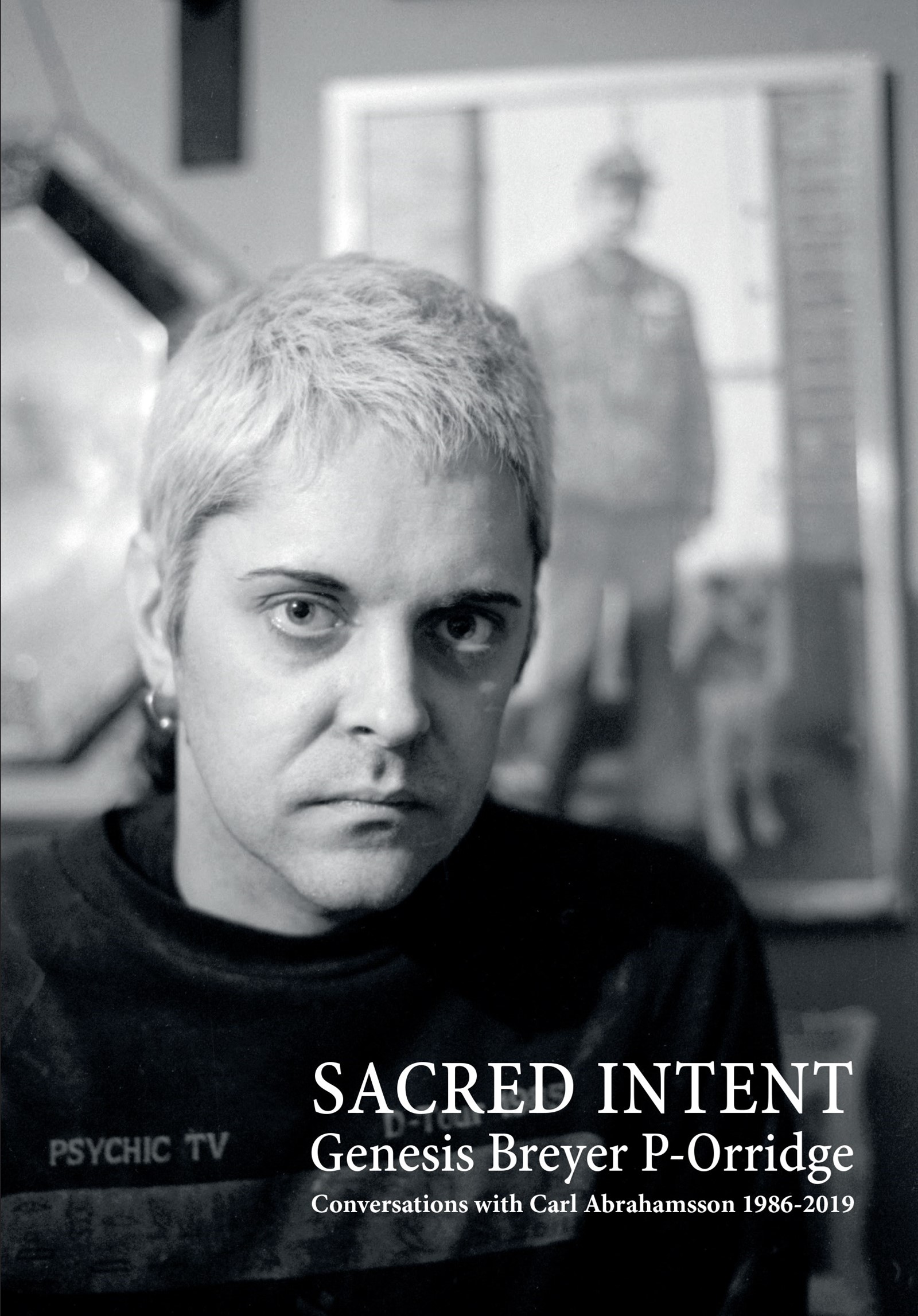

A new book, Sacred Intent, allows a closer look at the latter three decades of P-Orridge’s career, collating a series of conversations undertaken with the Swedish writer, photographer and filmmaker Carl Abrahamsson. Beginning with an interview in 1986 – spanning magic, art theory and gender revolution – to a final conversation in 2019 about living life in the shadow of leukaemia, Sacred Intent offers perhaps the most intimate portrait of the provocative artist yet. Here, coinciding with the release, we publish an exclusive extract from one of the final interviews in the book, undertaken via Skype in 2019.

Stockholm – New York, 2 November, 2019

Although frequently in touch via e-mail and different kinds of text messages, I wanted to talk to Gen “live & direct” again. But as I wasn’t planning any New York trips at this time, we decided that a Skype session would be the next best thing. We had by now decided to wrap up the book project, so that it could be published on Gen’s 70th birthday: 22 February, 2020.

Carl Abrahamsson: You mention pandrogeny already in our interview in 1988. There’s a strong sense of consistency.

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge: Oh yeah, and it’s also mentioned in one of those two red notebooks that Timeless published. There are three pages from 1986 where I say that pandrogeny is inevitable. Jarrett, who did the Polaroid show, found something in an interview where in 1978 or 1979 I mention something called “panthropology.” I don’t have any new ideas; they all started in 1979.

CA: Yes, but you have very good old ideas.

GBPO: And it takes 40 years for people to understand.

CA: I think also our book will be quite an eye-opener, specifically for people in the art world. There’s so much consistency and we have done a good job of, sort of, making little pit-stops in art history and talking about things that have to do specifically with that; and then drifting on into magical stuff, and then back again. By the way, how are things moving along with the autobiography?

GBPO: I’m writing some every day. There’s a lot to write! What I’ve focused on for the last three or four weeks is from being born to going to Solihull School, because that’s the least documented part of my life. I just finished the part of when I went to Jersey in 1964 and met “Scotch John.” You know the story where he asked me to stay and look after the prostitutes?

CA: No, I would love to hear that!

GBPO: I’ll send it to you. It’s really crazy. So, I’m writing and I’m thinking, “you were 14 years old and you nearly stayed in Jersey to run prostitutes.” Bearing in mind that there were no porno mags in Britain at all then; no sex education, nothing. No one had told me what sex was and then this guy shows me all these pictures of his prostitutes doing everything, and I’m thinking now, “is that why I do all these Polaroids?”

CA: Probably.

GBPO: That was my first ever connection with sex; with pictures of sex.

CA: How are you working on the book? Do you work sort of backwards or just drop in at different times in your life that you feel compelled to write about?

GBPO: Yeah, the second. It’s just interesting, thinking about threads that appear at times when I didn’t think they did. I notice that there’s a continuity to certain aspects. Like, one of my earliest memories is being blamed for something I didn’t do, which has continued throughout my life. You sort of think, “wow, karma, what is this program that we’re all in?” What I’m really finding is just ... Is there any kind of free will at all? Are we just living out previous karma? My father wanted to be a professional musician, he performed as an actor, he raced motorbikes, and all this stuff. I then end up hanging out with motorbike gangs, playing the drums, becoming a musician and being a performer.

CA: I know.

GBPO: Am I living out his karma? Is that what I do, and is that what all children do?

“You remember that we always said that we never wanted to rely on the creative projects we are involved with most deeply for basic living income, for fear of distortion of the central integrity” – Genesis Breyer P-Orridge

CA: Quite possibly. Which leaves no pressure at all on Caresse and Genesse ...

GBPO: I hadn’t thought of that one ... Oh, god! What have I done? (laughs)

CA: One of your strong points is not the enormous body of work in itself; it’s your sense of integrity. The work can radiate that inspiration just from the fact that it’s pure.

GBPO: Perhaps. There is purity of intent, a unity of purpose, and that’s why I’ve always said you have to look at it from the deathbed backwards. Can I be proud of what I do today, should I suddenly die? You know, you can’t try and self-analyse on the actual journey or it’s too confusing. You remember that we always said that we never wanted to rely on the creative projects we are involved with most deeply for basic living income, for fear of distortion of the central integrity; it inevitably compromises decisions. That’s why with TG, for instance, we kept it separate.

Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson paid his bills working as a partner in “Hipgnosis;” Chris Carter worked for his father’s various businesses; Christine Carol Newby worked as a stripper under the name “Scarlet;” and we were on the dole until, after a few years, our Industrial Records label was able to pay me minimum wage for working full-time for I.R./TG, and letting the entire downstairs of my squat be taken over for warehouse and office functions for I.R./TG too. We never joined a label. Not until it was already defunct, and then we just did re-releases. Before that, around 1976, C.O.U.M. hit this point where we were getting incredibly small grants off the Arts Council: like 300 pounds for a year, for an entire performance group ... They started writing to me and saying, “now you have to send in scripts for all the performance pieces you’re going to do next year so that we can evaluate whether we should give you any more money.” We wrote back and said, “look, that’s not how art works. You imagine it does, and people may produce things to fit in with your system to get income, but in fact if I want to sit and watch Coronation Street, yeah, that’s just as valid as me making art objects, because my brain is what makes the art. And my brain is entitled to go wherever it wants; not where you want it to go or fit in with your form.”

They just didn’t understand what I was trying to say, but that’s why we said okay, let’s stop C.O.U.M. And then TG started to make enough so that we weren’t beholden to anyone. We could still choose whatever records we wanted to do, how we wanted to do them, everything ... We had 100 per cent control, and we never did a deal because we knew they would immediately make us compromise. Remember the story with Virgin? When they saw the rave five-star reviews for The Second Annual Report they rang up and wanted us to sign to Virgin, and they said they wanted a demo tape and they also wanted the cover to feature Cosey showing her tits. And so we sent them a cassette tape; we broke it with a hammer so it didn’t work, and said, “no photos, here’s your demo.”

CA: Demo as in demolition.

GBPO: I want to breathe again, Calle. I’m so tired of this.

CA: I can certainly understand that.

“Just when they’re starting to think of me as an artist, now we’re a writer” – Genesis P-Orridge

GBPO: It reminds me of Brion Gysin in Paris. That last week, when he was just, “I’m so tired of this.” But he didn’t have enough to look forward to to keep struggling anymore.

CA: No, and I think you do.

GBPO: Yeah, there’s too many books to do!

CA: Exactly!

GBPO: Just when they’re starting to think of me as an artist, now we’re a writer.

CA: Yeah, but that’s art too. When you started out, it was with a kind of a violent attitude towards the body as such. I mean, I’m also thinking of Stelarc, of C.O.U.M., Chris Burden, the Viennese Aktionisten, all of that stuff. Why do you think that the transgression was so violent at that specific time?

GBPO: I think it was because we were close enough to the Second World War, and we had seen images of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and we had lived through the Cuba crisis. All those things made it seem desperate to wake everyone up before we did that to everyone. There was a rage at the stupidity; that people hadn’t stopped thinking in terms of war as a solution, because then they had the Korean war, and they had the Vietnam war; it’s like it just never fucking stopped. America’s been at war ever since the Second World War, somewhere, so I think that was a large part of it. With the Viennese it was an expiation of the guilt to coming to terms with the atrocities that occurred on their side; of course there were atrocities on both sides. Dresden was an atrocity, for example, by the allies. I think they were also trying to expiate and exorcise the demons of their genetic political structures. For people like me it was the sheer rage at the complacency of the middle class. In the 1960s, I think it was Harold Macmillan’s slogan to try and get elected that, “you’ve never had it so good.” That was the big slogan. He was a Tory of course, and they were saying, you know, “don’t rock the boat, everything’s perfect, you’ve got better wages than you had before the war, you’ve got houses being built.” You know, to replace the ones destroyed in the war. Rationing only stopped in 1953, or 1954. I actually experienced rationing for four years. I was too young to understand it, but I did. It was monstrous, and it was close enough to be both terrifying, and an abomination.

It was like, “for fuck’s sake, wake up’!” How do you do that without being violent? You do it by hurting the self, you know; by wounding the self as a symbol of the wounding that’s happening from the ignorance of the political structure. Certainly with me there was a lot of that. The hypocrisy and the double standards and the bigotry and the suppression of nature; of the natural order of the human body, our right to control our own skin. All of those things ... To me they were just anathema. How could I explain it but say, “it’s my skin and I’m going to do what the hell I want to it, and if I have to hurt it and damage it in order to get your attention then I shall, because I need your attention, because this is very, very important.”

We have to try and find out if there is any way at all for human beings to change their behaviour, because for 30,000 years we’ve been repeating the same violent mistakes with war and invasion and rape and pillage. You would think that any intelligent creature would realise that that was counterproductive.

So it was all those things. You know, when the Cuba crisis was happening and they told Khrushchev that the boats had to turn around that day. My mother waved me off and said goodbye when I was going to school. She gave me a kiss and hugged me, and said, “I hope I see you tonight, but remember I love you if you die.”

“We have to try and find out if there is any way at all for human beings to change their behaviour, because for 30,000 years we’ve been repeating the same violent mistakes with war and invasion and rape and pillage” – Genesis Breyer P-Orridge

CA: Wow!

GBPO: That’s how people really felt. I’ve talked to a lot of people from that era, and they all agree that it was really heavy. We thought we were all going to be exterminated by nuclear war. And when we weren’t, we thought we’d have a breathing space to try and generate common sense, and that’s when you get CND – the Committee for Nuclear Disarmament – which became the nursery of bohemians and beatniks, and eventually hippies. They did all their marches every year to protest the bomb, and that’s how the whole London underground grew, from that initiative. All of it grows from that. So that really is the key: the terror of obliteration.

CA: In that regard, and taking their experiences into consideration too, did you ever feel an aesthetic kinship with butoh?

GBPO: Yes, but later. I don’t know if it was actually a butoh performer, but when we started to be in touch with Fluxus, somebody had a book, or I read a book, and it was exercises by different Fluxus artists. One of the Japanese ones had written, “take 24 hours to get undressed.” That was like a Eureka moment. Because suddenly we could be violent in such slow motion that it wasn’t violent. Then it was literally how slow can we do it. And that’s when it started to really work, because I saw it as very painterly thing. You could take a snapshot of any moment and it would look like a really interesting photograph, but almost like an interesting painting. Or a still from a film. It just looked really intriguing, and we became a great believer in curiosity as being the key to communicating in that really artificial environment of the art world. To still generate enough curiosity, and be non-traditional enough that they had to stop and think and hesitate. They had to take a breath. Otherwise they wouldn’t make any connection.

When we did the Paris Biennale in 1975 people were watching us in our box all day long. We have all those photos. And the one in Milan, where there was a scaffolding outside, and my job was to climb the scaffolding up onto the top, and that, again, was meant to last one hour. On the way there I had to hang in all these weird positions. That’s a different kind of stress because it looked like ballet, but it hurt more than the other stuff. You know, hanging by one hand trying to find how to get to another piece of scaffolding, but to make it slow.

CA: In moments like that, did you ever think, “what the hell am I doing?”

GBPO: Yes! But I didn’t question the transmission. That one in particular, that happened in a dream vision, and somewhere in a notebook there is the original sketch of it. We’ve always had great faith in those visions. When they come like that we never, never doubt them.

CA: That said, are you still experiencing them in your present condition?

GBPO: Yeah. Not that kind exactly, but we’ve been having moments where we can see this and another world at the same time. It’s quite fascinating. And we have to really concentrate to decide which is the one that I’m still in!

CA: Do you see any kind of hindering or hampering of your creativity in general because of the physical stuff going on?

“We’ve always had great faith in those visions. When they come like that we never, never doubt them” – Genesis Breyer P-Orridge

GBPO: No, not at all.

CA: Good. The new Polaroid book is amazing.

GBPO: It’s like when we use rubber stamps and postcards and all kinds of small things. Polaroids are like the everyday stuff that people use. A lot of artists love Polaroids. When it was created it was not seen that way at all. They’re crude and romantic at once.

CA: In a way it’s like with the film format of Super 8. The Super 8 aesthetic evokes something completely different from other kinds of cinematic stock. There’s something having to do with home, and nostalgia and sentimentality. With Polaroids it’s this prurient thing, where you’re seeing something that you’re probably not supposed to be seeing. It always feels like a very private moment. If you see it, it’s like a “Peeping Tom” experience.

GBPO: Also it’s alchemical, because it’s just liquids, basically. The light strikes them and solidifies the image. Visual poetry and making magic. It’s not pixels, and it’s not the basic effect of light on film; it’s a really specific, unique process.

CA: I think it’s extra emotional because of the fact that the image also fades. If you leave it in the ligh – the very same light that once gave it life – it will fade away.

GBPO: Me and Jaye fell in love with them. If we saw something we particularly liked, we’d take ten Polaroids of the same thing, and we’d put them in collages and such. I really miss that.

CA: In this phase, do you have good dream recall? Do you dream differently?

GBPO: I dream every night very vividly, but most of the dreams are just ... busy. Busy stuff, arguing with people, trying to get things done, that kind of thing. We’ve only had a few real lucid dreams where we remember everything when we wake up. Those ones we write down because they usually seem significant, and you can always tell the difference in the quality. So there’s not a lot of change; maybe slightly fewer lucid dreams, and why that might be, who knows? My sleeping is really off. The other thing that’s bothering me is the breathing. But I’m alive and I can function and I can type, so ...

CA: Given that you have always looked at things through a kind of matrix of cut-ups, can you see that your situation right now is a cut-up too; in-between sickness and health, and in-between life and death. You’re in-between these extreme polarities.

“When I was in the hospital the last time, when I was in the ICU, they actually rang him up and said, “this is the New York Times and we’d like a quote about Genesis for our obituary.” So they just can’t wait to get rid of me!” – Genesis Breyer P-Orridge

GBPO: It’s funny you should say that because the editor, Tim, said to me last week, “have you thought about writing about mortality? Because you’re in this unique position.” I know what triggered it; it was because the New York Times rang him up again about their obituary of me. When I was in the hospital the last time, when I was in the ICU, they actually rang him up and said, “this is the New York Times and we’d like a quote about Genesis for our obituary.” So they just can’t wait to get rid of me!

CA: It’s weird. I mean, they’re great journalists and all, but I mean, that’s just cynical.

GBPO: What is it going to feel like, you think?

CA: What?

GBPO: A world ... A world without Gen in it.

CA: I’m trying not to think about it too much. But if I do, I’m just thinking of how blessed I’ve been. You know, we’ve worked together since 1986; we’ve never really had a disruption except for normal disruptions of time. It’s just been extremely valuable. We’ve made these three beautiful albums, and this book, and many other things, and it’s just a blessing. I don’t think I will have emotional problems with it. It’s just a matter of carrying on the work, like you did; you carried on the work. I will carry on the work, and then other people will carry on the work. It feels like a blessing to me.

GBPO: Good. Very good!

CA: Stay strong, and just keep on fighting, and keep working. That’s the key to it.

GBPO: It is. It’s all I got.

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge: Sacred Intent | Conversations with Carl Abrahamsson 1986–2019, published by Trapart Books, is out now.