2019 marks the centenary of the Bauhaus school of design. Here, we unpack some of the stories behind the most revered pieces of its output

“If your contribution has been vital there will always be somebody to pick up where you left off, and that will be your claim to immortality.” Walter Gropius, Bauhaus founder and grandfather of Modernism, believed that design, architecture, craft and art could be harnessed as forces for shaping a better future. His dedication to simplicity, accessibility, innovation and education formed the backbone of the Bauhaus school’s curriculum and a design legacy that continues to define built environments around the world. As the influential movement celebrates its 100th anniversary, a sprawling and seemingly endless schedule of events around the world is testament to the profound need for design revolution that saw the school’s students and masters tasked with redefining the way we live from the ground up.

While trends come and go, fashions change and style evolves, there are a handful of designs that resist obsoletion with timeless flair and finesse, classics that fight frivolous change with unprecedented quality and consideration for the needs of the user. Although there are many arguments that landmark furniture pieces are being devalued and defaced by the almost unstoppable blackmarket of fakes – many hiding in plain sight thanks to the budget-conscious procurement of interior designers and architects – there is no denying the enduring popularity of classic forms. These are the real stories behind the Bauhaus’ most iconic designs.

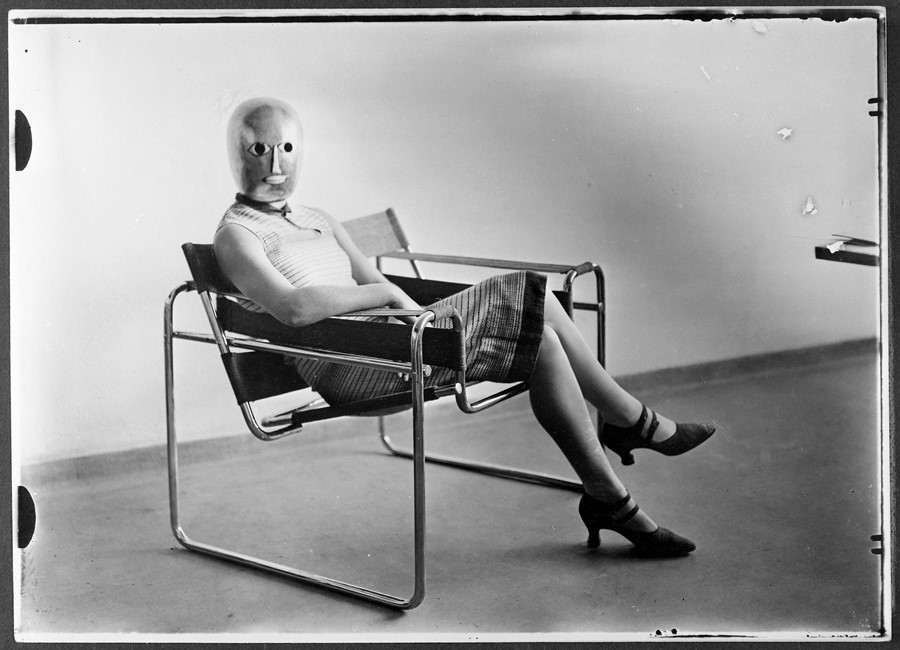

Wassily Chair by Marcel Breuer, 1925–1926 (above)

The sinuous steel of Marcel Breuer’s furniture designs has become synonymous with contemporary refinement. Ever-present in cinematic homes and the high-rise offices of Ballardian fantasy, the Model B3 Chair is arguably the most famous of them all. In spite of its regal standing near the top of the pyramid of defining Bauhaus designs, the cult classic was the result of Breuer’s desire to break out of the school’s wood workshop and into metal, inspired initially by the handlebars of the Adler bicycle he used to travel around the Dessau campus. It only became known as the Wassily Chair when, decades after its creation, Italian manufacturer Gavina coined the name having discovered that fellow Bauhaus faculty member Wassily Kandinsky admired the completed product so much so that Breuer produced a duplicate specifically for the artist’s personal quarters.

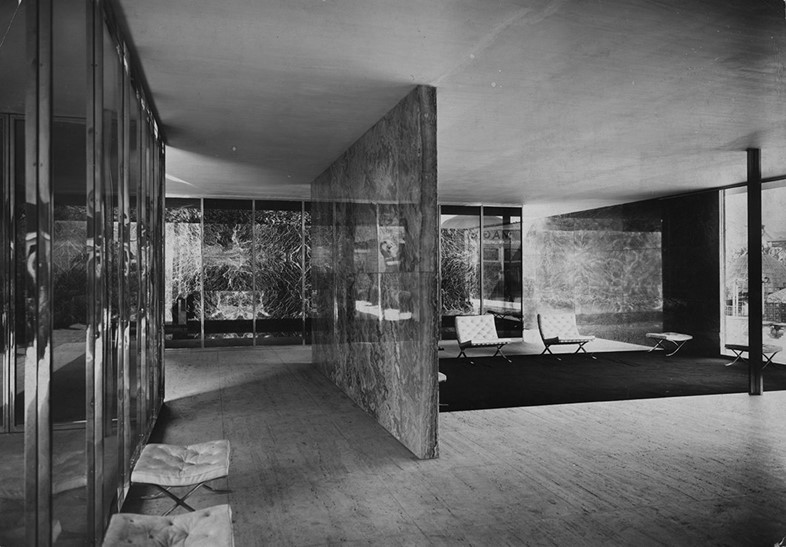

Barcelona Chair by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich, 1929

It has been said that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and there is not a single piece of furniture on this planet more relentlessly replicated than Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich’s Barcelona Chair. It has been featured in every fashion magazine, endless aspirational bachelor pads and in significantly more adult films than you might expect, but its first and most profound role was as part of the German Pavilion at the International Exposition of 1929 hosted by, of course, Barcelona. There is some irony to be found in the unparalleled fame of this chair, as it was not produced in accordance with the Bauhaus philosophy of creating furniture for the common man, but for Spanish Royalty to oversee the opening ceremonies of the exhibition.

Triadisches Ballett by Oskar Schlemmer, 1922

Described by the designer and Bauhaus master as “a party of form and colour”, Oskar Schlemmer’s avant-garde ballet is a psychedelic exploration of the relationship between figure and space. Originally a sculptor, Schlemmer rejected the rigidity and expressive restrictions faced when using plastic, metal and wood, instead embracing choreography and costume and creating the most widely performed avant-garde artistic dance. The Triadisches Ballett, first conceived in 1912 in collaboration with dancers Albert Burger and Elsa Hötzel, premiered in Stuttgart in September 1922 and toured until 1929, acting as something of a missionary figure, spreading word of Bauhaus education and principle.

Tea infuser by Marianne Brandt, 1924

The recent Anni Albers retrospective at Tate Modern has drawn the eyes of art and design lovers to the so-called forgotten women of the Bauhaus, but long-time admirers of the school are more than familiar with another poignant alumnus, Marianne Brandt. Brandt eschewed more traditionally female roles in the weaving workshop in favour of a career in metal – a move championed by László Moholy-Nagy, who identified her unique talents early in her studies. Joining the Bauhaus in 1923, Brandt became a star student of the metal workshop and outshone all of her male peers. Following her success as a student and the impressive body of work she was amassing, she was invited to join the workshop as a tutor and worked alongside mentor Moholy-Nagy in shaping the future of metalwork.

Brno Chair by Mies van der Rohe and Reich, 1929–1930

Following its unveiling at the International Exposition of 1929 in Barcelona, Mies van der Rohe and Reich’s aforementioned Barcelona Chair became one of the signature chairs to adorn the now protected Villa Tugendhat in the Černá Pole neighbourhood of Brno, Czech Republic. Designed by Van der Rohe and built between 1928 and 1930, the reinforced concrete villa was created for Fritz Tugendhat and his wife Greta, and quickly became an icon of Modernist architecture. It is unsurprising, therefore, that this project saw the birth of another widely recognised design classic in the form of the Brno Chair, also known as model number MR50. The designers’ love of clean metal lines defines the form of this piece and, despite its considerable weight (particularly in the solid flat steel version), it has become a staple of chic offices and homes alike.