Having visited North America’s arid Mojave desert repeatedly at the start of the 1960s, the late British architecture critic Reyner Banham is quoted as saying: “In a landscape where nothing officially exists (otherwise it would not be ‘desert’), absolutely anything becomes thinkable, and may consequently happen.” He also suggested that there are only two types of people: those who love the desert and those who hate it.

Celebrated in Phaidon’s latest book Living in the Desert, dune-strewn landscapes have become a canvas without geographical boundaries for architects and idealists alike. Roughly one third of the world’s land mass is covered by desert, yet those drawn to settle in these remote regions are often looking for an escape from the rest of the world. Dry silence and scorched sand make it almost impossible for greenery to flourish and anyone choosing to exist there is entering into an unavoidable and relentless battle to sustain life. To live in the desert requires resourcefulness and an unwavering respect for the forces and life cycles dictated by nature, something many inhabitants of these harsh landscapes take great pride in mastering and meditatively devoting their energies to. Regardless of mother nature’s best laid plans, with the presence of humanity comes a need for shelter – enter, the architects.

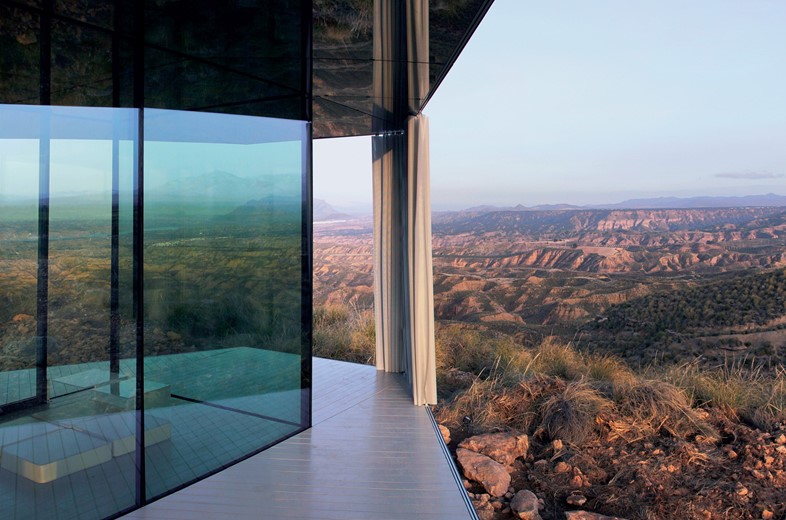

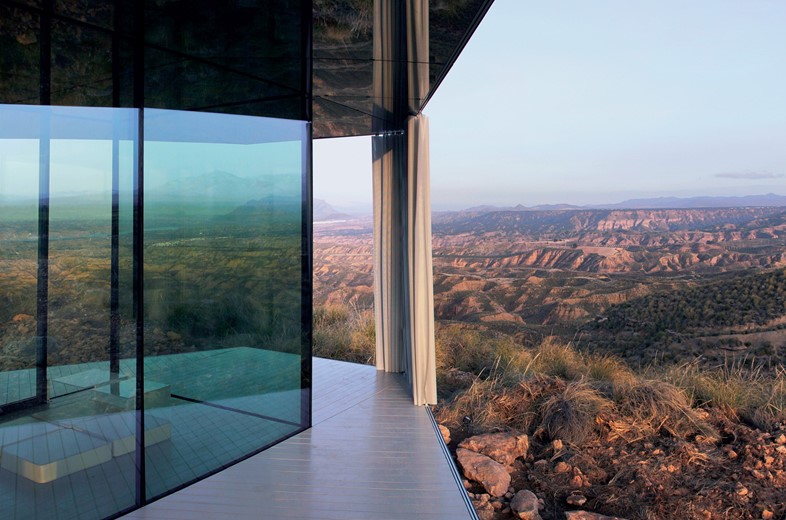

While it may seem unnatural to create a home in a place with no water, plants or signs of life, the outlandishly engineered dwellings featured in Living in the Desert are testament to the perfect pairing that is architecture and the desert. Scale is pivotal in our perception of everything from art to urban planning, but in the deserts of Earth – where horizons are immeasurable and landmarks scarce – scale is warped, indecipherable at a glance and a challenge to the observer. As such, the incomprehensible emptiness of a desert landscape magnifies the profundity of any building erected, and in return these solitary monolithic dwellings act as a catalyst for the sense of isolation that will consume the inhabitant.

Arthur Wortmann, the first editor of Dutch architecture periodical Mark, used to say that the smaller the window, the easier it is to frame a pleasing view. What Wortmann’s statement fails to address is the inescapable visual stimuli of a desert’s almost extraterrestrial existence. Subsequently, architects have addressed this earthly anomaly with unprecedented structural strategies that do not attempt to contain the horizon, but to incorporate a 360-degree panoramic experience into a home, one that often demands a house’s entire orientation to be flawlessly choreographed with nature’s unchangeable movements.

It is not just architects and adventurous homeowners who have found enchantment in the mythical qualities of desert terrain. Vast expanses of lifeless earth have become the muses and catalysts sought by writers, artists and directors throughout history. In Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1970 film Zabriskie Point a series of surreal events are shown to unfold in California’s Death Valley, while utopian features and wartime dramas such as The English Patient allow the struggles of a desert environment to amplify the desperation and strife of their central characters. What is undeniably apparent in every portrayal of desert life, whether it be fictional or documentarian, is that being able to adjust to such extreme seclusion, silence, and self-reliance is necessary for a way of life that is in many ways the polar opposite of our currently prevalent urban ideals.

Living in the Desert, published by Phaidon, is out on November 1, 2018.