In honour of Word Week on AnOthermag.com, we take a look at some of the 20th century’s most influential word artists

From writing and talking about art, to actual words on canvas, art and words have forever been inseparable. So as part of AnOther's #WordWeek festivities, we wanted to take a look at their role in the visual arts throughout the last century. From Marcel Duchamp to Martin Creed, Ed Ruscha to Tracey Emin, text has played an important part within the context of modern and contemporary art, and continues to be a vital part of artists’ practices.

Somewhere between 1907 and 1911, the Cubists began to paint letters and words into their still lifes. By the 1920s, the Surrealists married poetry and visual art in an attempt to illustrate the unconscious; meanwhile, the Dadaists manipulated language in playful configurations. By the time artist Henry Flynt established the term “concept art” in an essay in 1961, the integration of text into the visual arts had become a normalised practice.

"Whether through a bold political statement, a probing question, the use of restricted vocabulary or a line of poetry, words in art push boundaries, they shock and seduce"

Text has appeared across modern and contemporary visual art – in signs, slogans, newspaper print and neon lighting – as a reflection of our cultural moment. We are a society perpetually engaged with words, in which advertising and mass media play a central part in our lives. Whether through a bold political statement, a probing question, the use of restricted vocabulary or a line of poetry, words in art push boundaries, they shock and seduce. Here, AnOther presents its top 10 word artists.

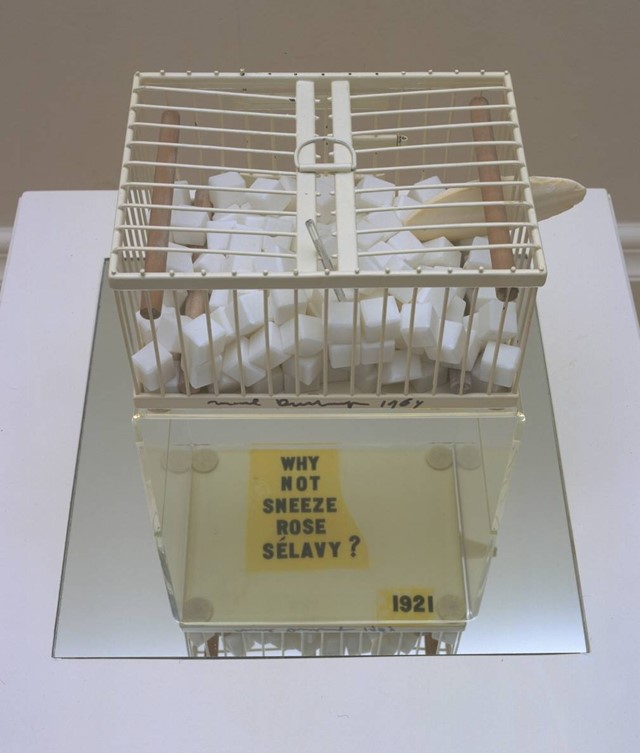

1. Marcel Duchamp

Hailed as the father of conceptual art, French-American artists Marcel Duchamp was a sculptor, painter and pioneer in plastic art. Intent on challenging the mind, and not simply the eyes, of his viewer, Duchamp playfully integrated objects and text. In his “readymade” sculpture, Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? (1921), a cuttlefish bone, a thermometer and ice cubes (made of marble) are enclosed within a bird cage. Duchamp aimed to create a “mythological effect” by asking the viewer to understand how the original object – the bird cage – has been changed by the presence of the other objects and words.

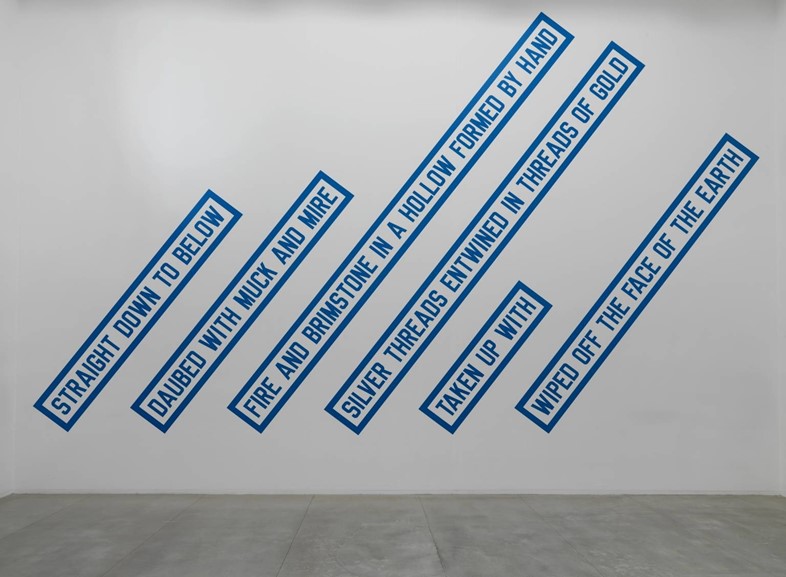

2. Lawrence Weiner

Among other conceptual artists throughout the 1960s and 70s, Lawrence Weiner challenged traditional notions of the art object. Born in the Bronx in New York in 1962, he worked on an oil tanker in North America before turning to visual art – and then to language. Weiner’s wall texts – written in nondescript text – focus on the potential of language to serve as an art form, though their subject matter is often material; brick wall, industrial enamel, earth, dust.

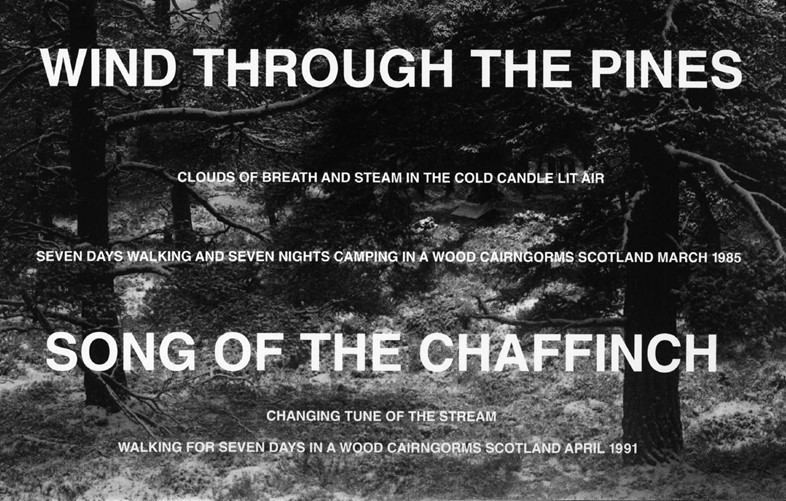

3. Hamish Fulton

London-born artist Hamish Fulton likes walking, and he likes the number seven, which recurs throughout his work as a ‘magic’ number. In 1969, Fulton walked in Scotland, The Netherlands, Norway, Lapland, Iceland, Canada, Mexico, Peru, Argentina and Tibet. The titles of his works are often romantic and pastoral, recalling his observations and emotions through his many solitary rambles. Plain typography is often layered over photographs of the landscapes.

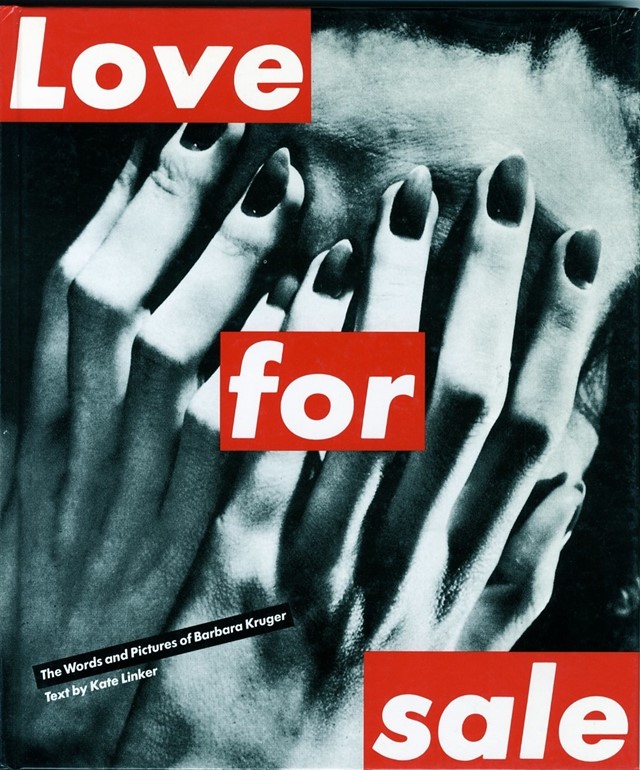

4. Barbara Kruger

Taught at art college by Diane Arbus, Kruger worked as a designer for the magazine House & Garden in New York before changing career paths and creating some of the most aggressive and controversial art of her generation. Like many conceptual artists, she uses word art to publish a political agenda. Her declarative statements – most famously, “Your body is a battleground” and “We don’t need another hero” – are written in Futura or Helvetica type face, and use pronouns to challenge culturally accepted constructions of power and identity. Kruger’s works are antagonistic, merging image and text and adhering to contemporary theories of semiotics and deconstruction in linguistics. She explores gender, identity and consumerism through techniques of advertising and mass communication, like other feminist artists of her generation, including Jenny Holzer and Cindy Sherman.

![[no title] 1979–82, Jenny Holzer, © Jenny Holzer](https://images-prod.anothermag.com/786/azure/another-prod/310/0/310489.jpg)

5. Jenny Holzer

Holzer studied printmaking and drawing before turning the focus of her career to language, installation and public art. Like Kruger, she belongs to a group of artists who, throughout the 1980s, attempted to create feminist commentary in a society of objectification and consumerism. Infiltrating public spaces with large-scale text-based pieces, Holzer’s work is displayed on advertising billboards and projected onto the sides of buildings. She aims to introduce her ideas into the public domain, though she also focuses on merchandising, selling slogan t-shirts and badges on the streets of New York.

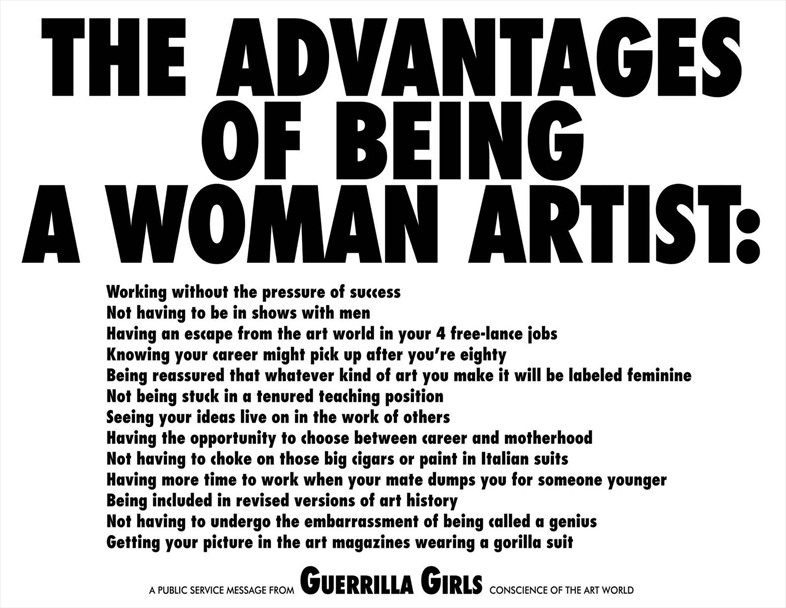

6. The Guerrilla Girls

In 1985, the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened an international survey of contemporary painting and sculpture. Of the 169 artists exhibited, only 13 were female. In response, an anonymous group of protest artists wearing fearsome gorilla masks began to create work which highlighted sexism in the art world. The group produced art bearing slogans such as, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?”, whilst many pieces directly tackled curators and art critics by name, accusing them of gender discrimination in their focus.

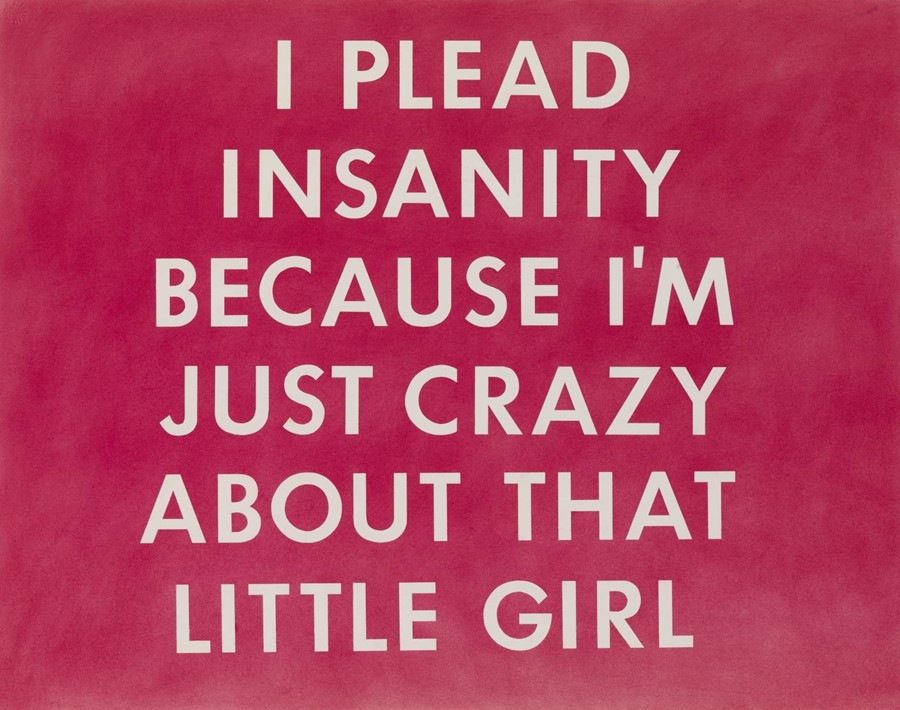

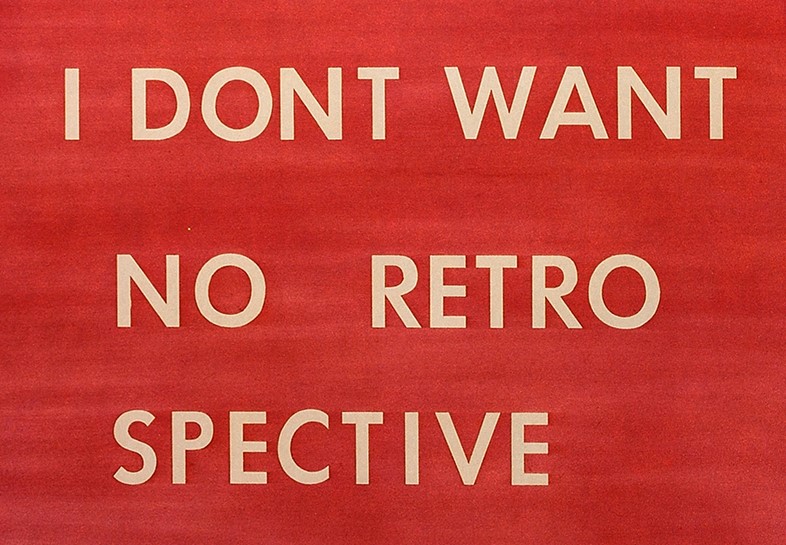

7. Ed Ruscha

Ed Ruscha rose to prominence in Los Angeles in the 1950s through his collage work. But he refined his collage, and throughout the 1960s and 70s, focused on the isolation of language and graphics. His work comments on the imagery of commercial advertising culture. After a phase of painting with organic substances – foods, blood and even the medicine Pepto-Bismol – Ruscha returned to his characteristically deadpan and humorous word pieces.

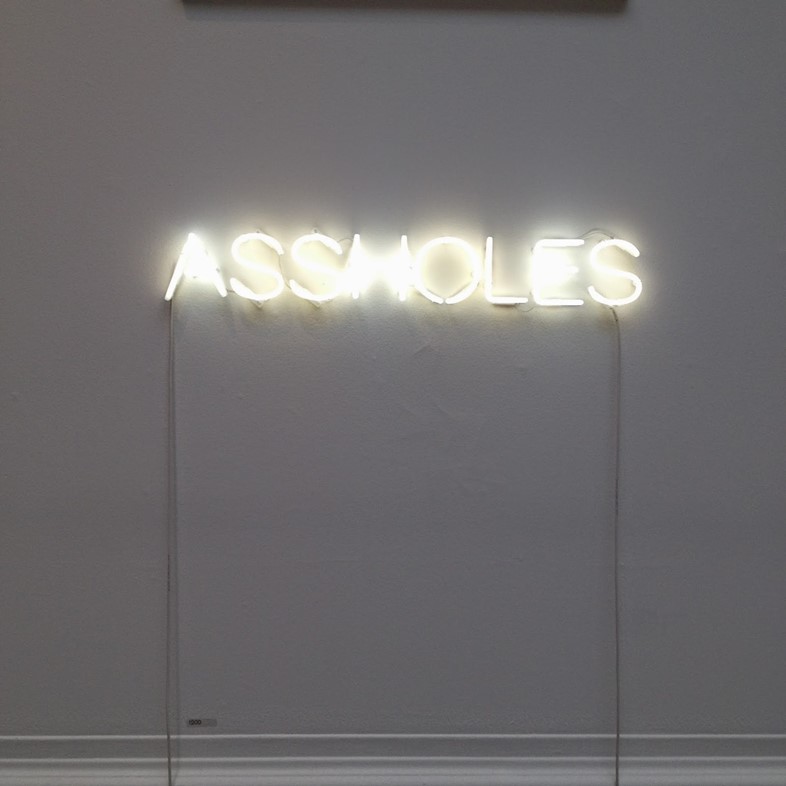

8. Martin Creed

Creed graduated from the Slade School of Fine Art in 1990, and has since worked as a sculptor and installation and conceptual artist. His works recall those of Duchamp in their interrogations of the art subject and in their placement of disparate objects – dentists’ equipment, Christmas decorations, a dishwasher. Like Duchamp, Creed’s point is that it is the objects’ relationships to each other, not their intrinsic qualities, which give the artwork its meaning. He works in public spaces, adorning the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art with neon slogans or filling a room with balloons at the Southbank Centre in London.

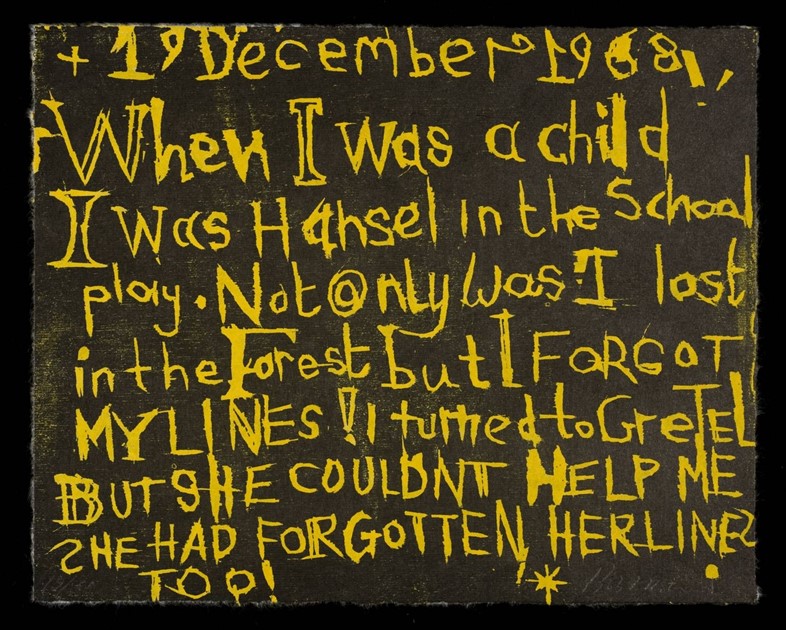

9. Bob and Roberta Smith

Also known as Patrick Brill, Bob and Roberta Smith has been producing slogan art since the 1970s. Musings on art, politics and popular culture, the brightly coloured lettering is painted onto textile banners or recycled bands of wood. Brill also lectures on education in the arts, and in 2006 he curated the exhibition Peace Camp on Brick Lane, which explored artists’ perceptions on peace.

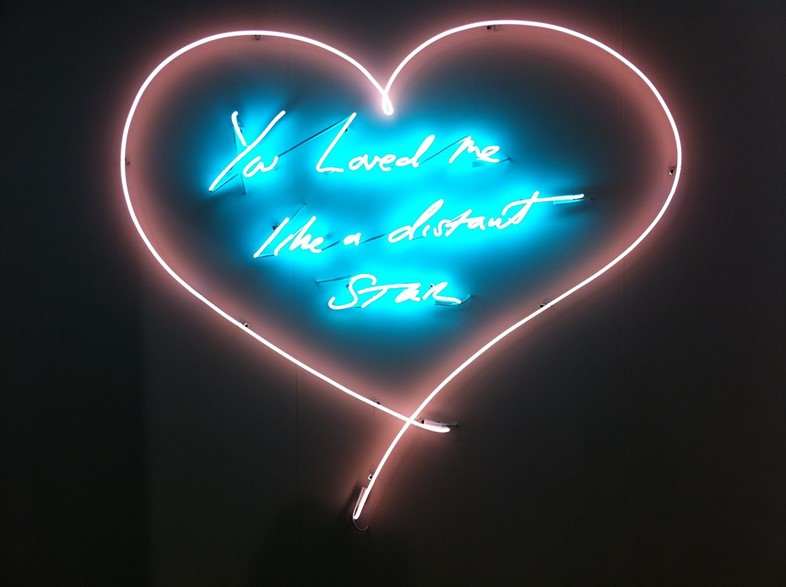

10. Tracey Emin

Tracey Emin’s work is nothing if not controversial. One of the Young British Artists, she was picked up by Charles Saatchi and exhibited in his Sensation exhibition in 1997, was Turner prize nomined in 1999, represented Britain at the 2007 Venice Biennale and in 2011 was appointed one of the first two female professors of drawing at the centuries-old Royal Academy. Emin has earned these accolades, producing works of art in drawing, painting, sculpture, video, photography and needlework. Her neon slogans, often produced specially for friends, including George Michael and Kate Moss, have fetched up to £60,000 at auction. More often than not they pose poignant questions or statements, touching on relationships, love and loss.

Text by Harriet Baker