To coincide with the release of a new book charting his exceptional career, Holly Black introduces the legacy of Japanese photographer Domon Ken

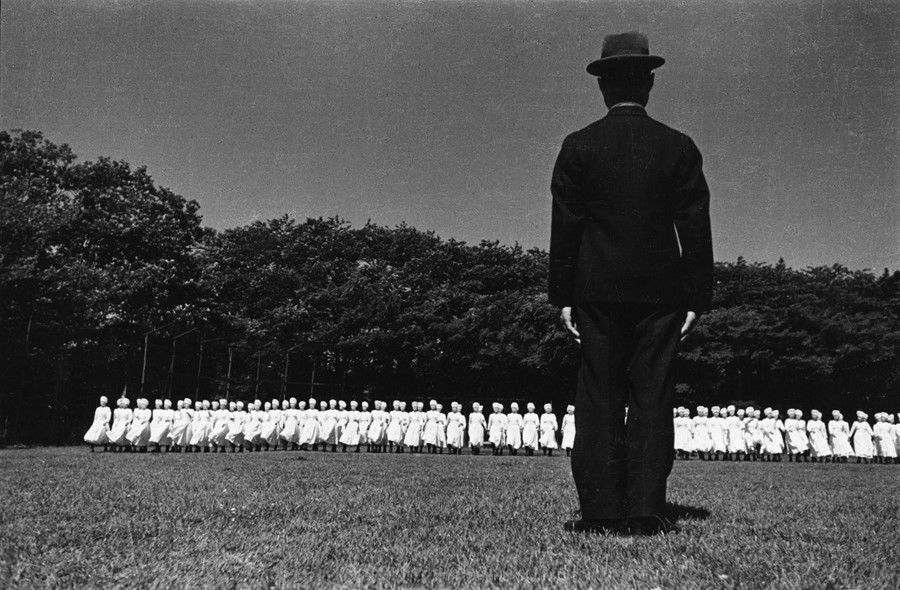

Despite his exceptional fame in Japan, Domon Ken has remained largely unrepresented overseas. This is probably in part because the man himself had no decided interest in the world beyond his native shores, preferring to point his camera at the rapidly changing society he had always called home. His unwavering commitment to social realism earned him a reputation as ‘the devil of photoreportage’, and his tenacious devotion to his craft was matched only by his ferociously competitive spirit.

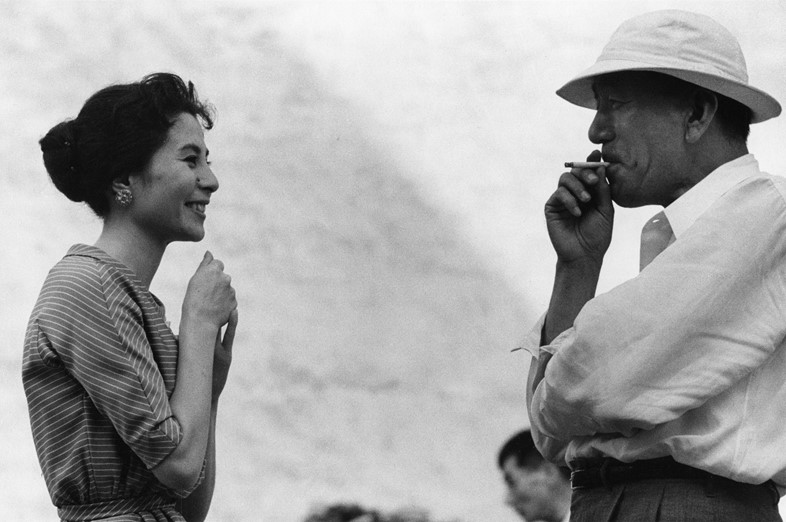

Domon came of age at the birth of the Showa era, a hugely influential period that saw the country actively embrace Western culture and trade after centuries of insular, practically non-existent foreign policy. The interest was reciprocated, and a huge demand for Japanese photojournalism extended as far as the US. After a false start as a painter, Domon secured a position working for commercial photographer Natori Yonosuke, but he soon became disenchanted with his lack of recognition and solicited commissions from national publications, with his big break coming in the form of a shoot for Life magazine in 1938.

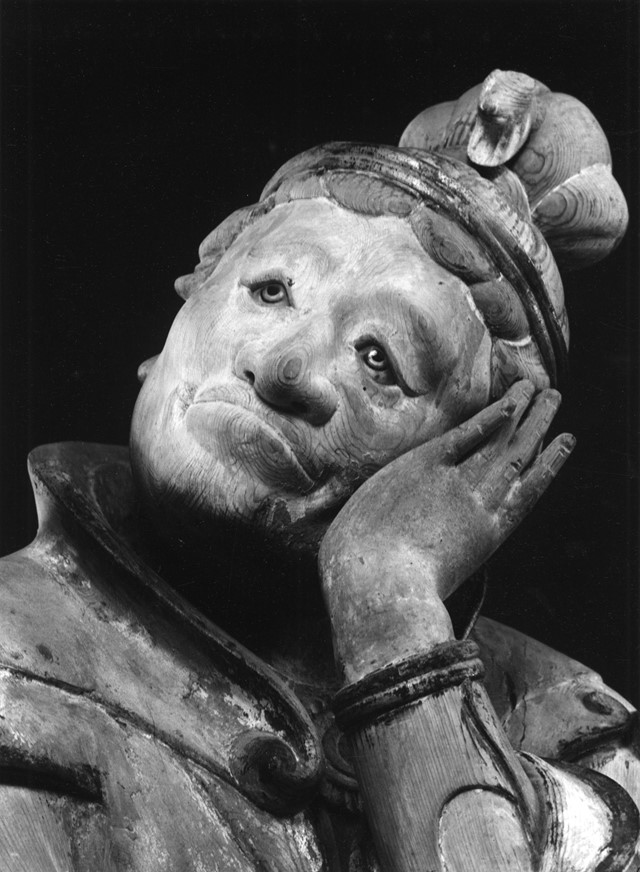

It wasn’t long before Domon was being heralded as a master of the realist form, with his enigmatic images of street life in downtown Tokyo, as well as everyday rural life beyond the capital. With the eruption of the Second World War that all changed. Domon was shocked by the oppressive propaganda thrust on his creative process by government regulations, and countless publications either folded or were disbanded. Terrified by the idea of being sent to the front line, Domon retreated into more reflective projects, including an ongoing series based around bunraku puppet theatre.

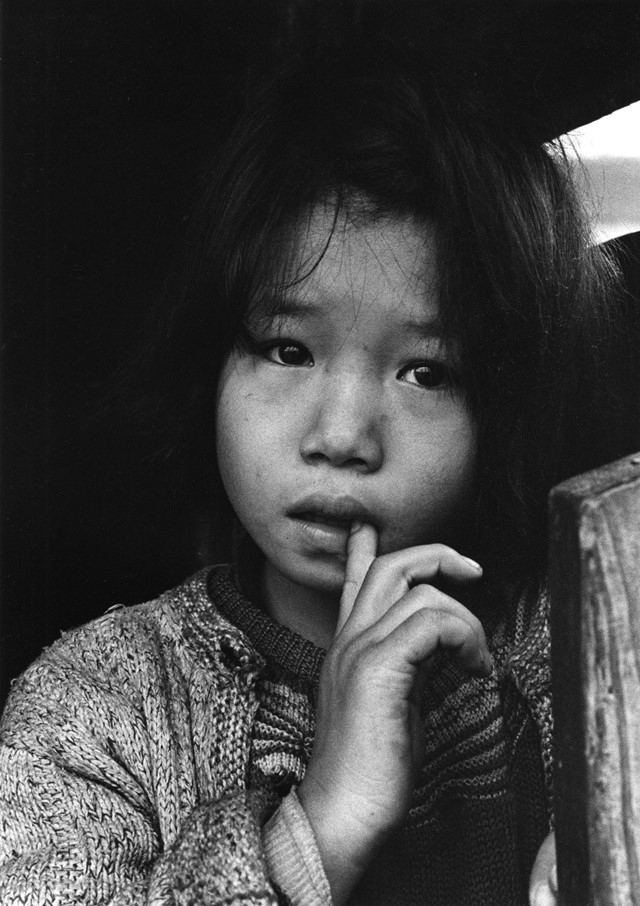

After the war ended Domon was able to fully realise his potential in regards to capturing the fleeting nature of human existence. His candid images of life in the war-torn, rubble strewn cities are both visceral and strangely romantic. They document a bizarre moment in Japanese history where the very fabric of accepted society was torn down (the Emperor’s surrender and admission that he was not a divine entity carved a shocking chasm through enshrined religious convention). He photographed glamorous women outside burnt-out buildings; joyous, impoverished children; created enigmatic portraits of the country’s greatest poets, actors and artists and also experimented with spiritual landscapes depicting the country’s ancient temples and shrines. His unwavering belief that beauty should always embody strength was something that always remained startlingly clear in his images.

Perhaps the biggest test of this ideology came from a series made some 13 years after the dropping of the atom bomb. Domon travelled to Hiroshima on commission, but became so fascinated by the horrifying consequences of the attack that he returned to the city six times in as many months. He documented hospital patients receiving plastic surgery, as well as mutilated civilians and children with related birth defects. The series shocked the Japanese public, who had been widely shielded from the irrevocable effects by the government. The horrors of war proved too much for many, and the photographer was widely criticised for supposedly exploiting the results of these cruelties. However some saw his work for what it truly was: a master stroke in the advent of contemporary photography. Nobel Prize winner Oe Kenzaburo declared “to depict living people who are fighting against the bomb, rather than the world of those who have died because of the bomb, is to face up head-on to the essence of art from and entirely human perspective”.

Domon Ken: The Master of Japanese Realism by Rossella Menegazzo, Takeshi Fujimori and Yuki Seli will be available July 11, 2017, published by Rizzoli.