Thai-Australian artist Nathan Beard navigates hybrid perspectives by reframing objects uncovered at his mother’s abandoned home

Who? A contemporary artist born to a Thai mother and Australian father, Nathan Beard is preoccupied with the notion of how identity is forged, and how cultural legacies are informed and shaped by personal histories. He has also examined identity on a much larger scale by investigating the thoroughly Western, museological presentations of South-Asian objects in institutions such as the British Museum, as well as the gaudy, ostentatious embellishments of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, where he spent several weeks in residence in 2015.

This body of research also directly informed another residency at the famed Jingdezhen Pottery Workshop in China. Here, he pieced together the fractured viewpoints of what he calls ‘cultural imperialism’ and fused them with the localised history of the Chinese ceramics industry. Using photographs of ancient, spiritual Thai objects taken through the glass at the British Museum, he produced his own copies that had inherited a certain amount of warping through the process of being photographed. The resulting artefacts were part of a show wryly titled Oriental Antiquities, named after the museum gallery that originally inspired him.

“My mixed race background offers up an in-between-ness,” he explains. “There’s a sense of hybrid perspective that allows me to explore how these influences are confused and how there can be a form of slippage apparent in their interpretation… I also have a complex relationship with these spaces, because I genuinely enjoy them, so there’s a personal conflict there.”

What? In his latest body of work, recently on display at the Gallery of Western Australia, Beard presented an ongoing intervention with his mother’s derelict house in Thailand, which she abandoned over two decades ago. “When my uncle was diagnosed with a terminal illness there was a sudden urgency to return to Thailand. He had always kept an eye on my mother’s house since she locked it up after my grandma died, but of course he couldn’t do that any more. Going back was like opening this vault of memory. It had this strange, subliminal familiarity because I had been to the house as a child, although I don’t have any concrete memories of it.”

Struck by the evocative power of the space, the artist enlisted friends from Bangkok – along with his mother and aunt – to stage an intervention within the untouched building. “We only had one night to do as much as we could; we took photographs and made a film, as well as installing a neon sculpture on the wall. It’s based on a Thai proverb written in my mother’s handwriting and roughly translates to ‘leaving home is like a bird leaving its nest’, which chimed with the idea of a homecoming.” He also became preoccupied with the portrait photographs that adorned the walls of the house. “With this archive I’m not only encountering images of my young self but also a family tree of deceased relatives from my mother’s side of the family, who I never got to meet. There was this profound sense of melancholy, looking through this collapsing of time through an accumulation of imagery. These worn, printed images have such a strong, redolent quality.”

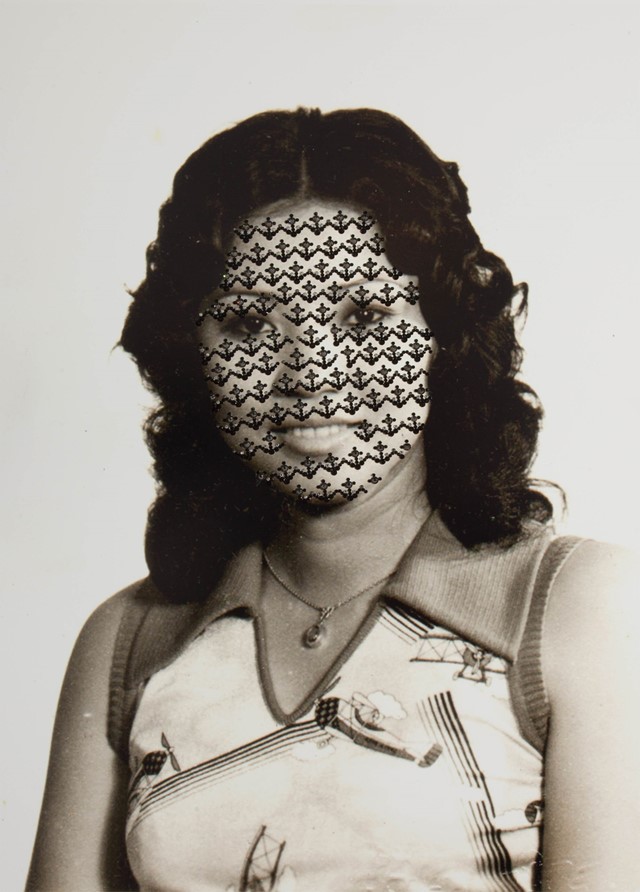

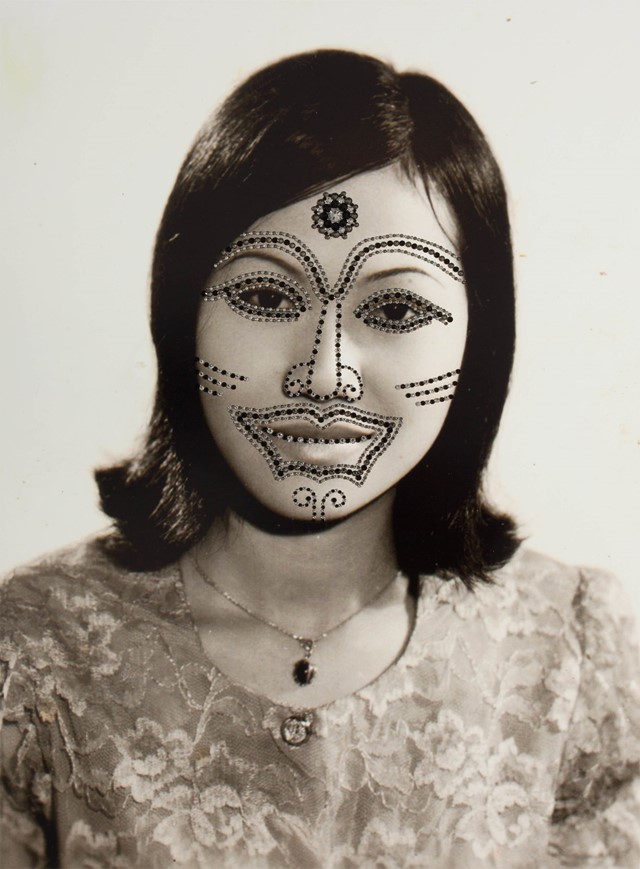

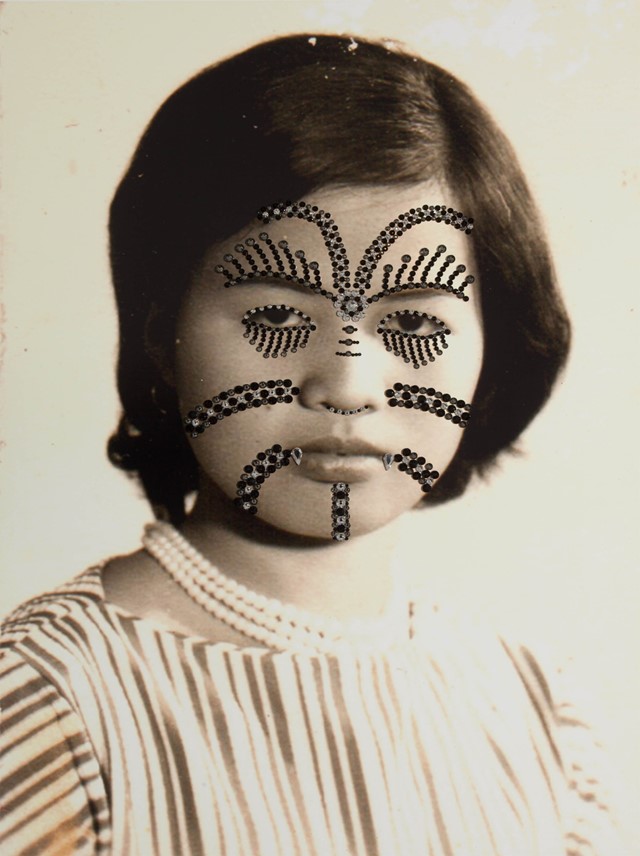

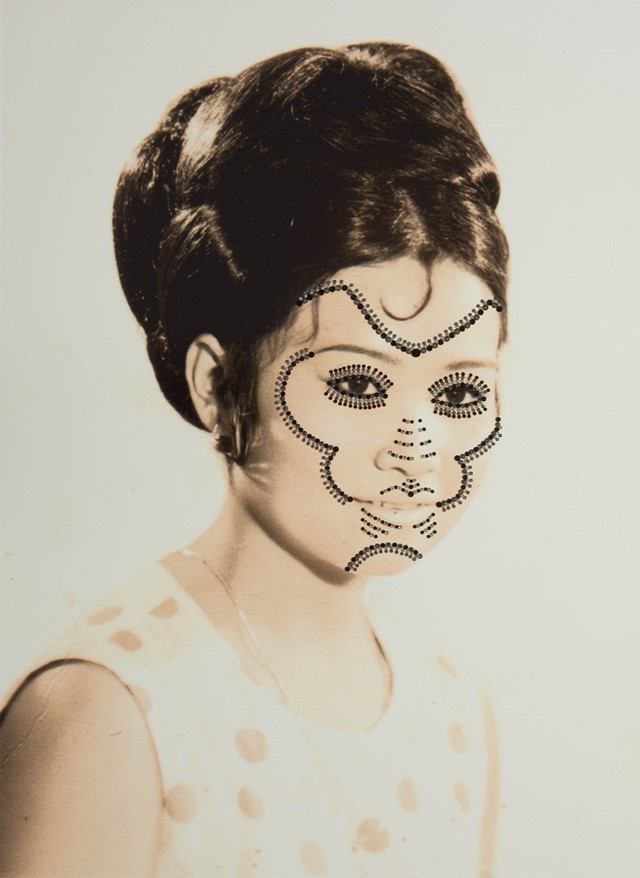

Beard took these images and began experimenting with embellishment, adorning them with crystals to mimic patterns found in Thai silk patterns; creases found in the face of the Buddha; and even motifs employed by Alexander McQueen. This might seem like a departure, but the inspiration comes from the fashion designer’s own in-depth investigation into clashing cultures, and an intense relationship with his mother. This struck a chord with Beard, as this entire body of work was based around “my mother as a central focus, as a way to approach an aspect of my family history that I’ve been estranged from. I was trying to build a relationship through her.” This sense of familial connection is also manifested in several of the portraits that are adorned with crystal tears: “those images are different, because they only depict the family members I actually met”.

These intimate bonds also course through the contemporary images produced on that one night in the house. Against the neon inspired by her own hand, the artist’s mother occupies a disquieting, empty space that calls to mind issues of mortality, whether that is in the form of a ritualistic burial setting, or surrounded by the photographs of her lost relatives.

Why Far from revelling in superficial aesthetics, Beard carefully considers issues surrounding ornamentation and craft, especially in regards to his Thai heritage. “I’m interested in processes of adornment that are associated with low-level work, which are often viewed as feminine. I’m trying to push these ideas into a new realm and disrupt them. With the crystal portraits I’m referencing the Thai space my mother curated in my home. She created shrines filled with golden figures and sparkles, all of which are really important to her culture. In Thailand you see these shrine spaces everywhere, but there is a high level of sincerity – these kitsch spaces are venerated.”