From Mae West's pillowy pout to a feminist retelling of Venus and Adonis, the early 20th century saw rural England transformed into an idyll of Modernist art and literature, a new London exhibition demonstrates

In the early 20th century, rural Sussex was cast as a kind of arcadia for artists and writers of diverse practice, whose spells in the countryside were acts of both retirement from and rebellion against the modern world. Today, the Modern Gothic architecture of Two Temple Place provides the setting for an exhibition of the work of said artists who were driven to abandon the metropolis for the county’s rolling hills. Sussex Modernism: Retreat and Rebellion, curated by Dr Hope Wolf, proves the biographical and conceptual links and detachments between members of the modernist community, with the common thread of being “out of place”. “There is a sense that modernists in Sussex identified themselves [that way] – partly to emphasise their metropolitan and cosmopolitan interests, and partly to express the experience of living in uncertain times; this was a world in which it was difficult for anyone to feel at home,” remarks Wolf in her introductory essay. Here, AnOther charts some of the key works of the exhibition that came to define Sussex Modernism.

Mae West, by Edward James and Salvador Dalí

In 1934, Edward James, a collector and patron of the Surrealists, moved to his family hunting lodge in the midst of a scandalous divorce. “But James attracted Surrealist visitors, who fuelled his decadent rebellion against mainstream culture and helped him to fashion an alternative fantasy world,” writes Wolf. The most notable piece is a sofa shaped to replicate the lips of Mae West, designed in collaboration with Salvador Dalí. It has long ceased to shock, “but in a grand house in the countryside it would have stood out strikingly from the more prudish, tasteful domestic decoration of the time,” she continues. Monkton House also boasted quilted walls, carpet depicting a dog’s footprints, and a purple exterior with cast palm tree columns.

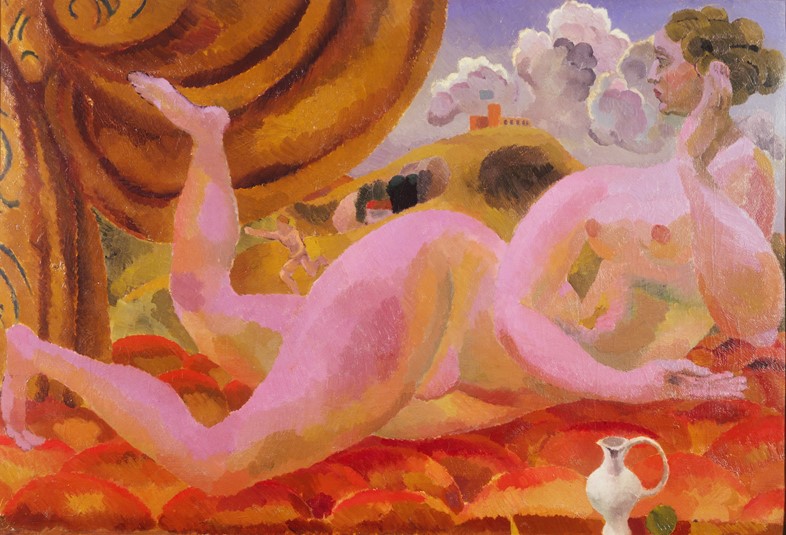

Venus and Adonis, by Duncan Grant

The Bloomsbury Group moved to Charleston House, Firle, in 1916. Unlike many of their modernist contemporaries, it was avowedly agnostic or atheist, feminist, and open to same-sex and polyamorous relationships. They sought to “blend beauty with utility, art with craft,” and brought to Sussex the imagery and bright colours of art from continental Europe. Duncan Grant’s Venus and Adonis is a satirical take on the classical myth, which refuses the narrative of male domination through its portrayal of a gargantuan Venus and belittled Adonis.

As well as being a feminist retelling, his version of the story is a continuation of the political position that brought him to Charleston during WW1. “Grant, a conscientious objector, had refused to enlist, and was required instead to work on the land,” writes Wolf. “In light of this, his mockery of machismo is perhaps indicative not only of a feminist agenda but also a pacifist one.”

Icon, by Eric Gill

Sculptor and typographer Eric Gill was a key member of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic, an organisation that described its move to Ditchling village as “an exodus from an enslaving industrial system that denied the workman responsibility for his creations, and also as an escape from a culture that preferred to worship money rather than God”. His works as a member of the Guild were controversial at the time, both to his cohort and the public, due to their eroticisation of religious imagery. An early example is Mulier, a statue of the ‘Blessed Virgin Mary’ pinching her nipple, which was commissioned by Bloomsbury group member Roger Fry, but later refused. Icon, a later work – from 1923, when Gill was a member of the Guild – shies away from nipple-pinching in favour of a warm embrace, but at the time, particularly for a staunch Catholic, would have been similarly controversial. In 1989, cultural historian Fiona McCarthy published a book on Gill that disclosed incestuous relations with his daughters, which have “deeply troubled his idealisation of ‘retreat’, and cast suspicion upon his attempts to set up cloistered communities away from prying eyes”.

Beach and Star Fish – Seven Sisters Cliff, Eastbourne, by John Piper

In Beach and Star Fish – Seven Sisters Cliff, Eastbourne, John Piper clearly depicts a Sussex coastal scene. But while the setting was on British soil, the work was “pieced together using style inspired by the paper collages pioneered by the Dada movement” and distinctly continental. “In the context of popular resistance to outside influence, modernists often used the coast as a subject through which to create unsettled works that explored themes of ‘inbetween-ness’,” says Wolf. And in Beach and Star Fish, Piper challenged the view of Sussex as a kind of idyll, and hinted at both military and civic strife: “The fragments of newspaper refer not only to Nazism in Germany but also suggest how capitalism and profit-making had transformed National Socialism. Adverts for English private schools are pasted alongside the news reporting: was Piper making an implicit critique of English society, narrowing the gap between the two countries?”

Saul Steinberg, by Lee Miller

Lee Miller moved to Farley Farm, Muddles Green with her partner Roland Penrose in 1949. “The house became a rural retreat for artists who opposed the mainstream culture and politics of the day”, and saw visits from the likes of Pablo Picasso and Henry Moore. Another such visitor was New York cartoonist Saul Steinberg, who Miller photographed in 1952 pretending to draw The Long Man of Wilmington – a chalk giant thought by some to have originated from the Iron Age. Miller established a tension between the city suit and the country walk, and “in part encouraged the placing of ‘modernism’ and ‘Sussex’ in an antagonistic relationship”. According to Wolf, “the photograph replicates a familiar opposition, so prevalent in literature and art, which associates the city with the new and the now, and the country with consistency and the past.”

Sussex Modernism: Retreat and Rebellion runs until April 23, 2017 at Two Temple Place, London.