Challenging, provocative and utterly compelling, Siberian photographer Nikolay Bakharev's portraits lure viewers into his strange and erotic world

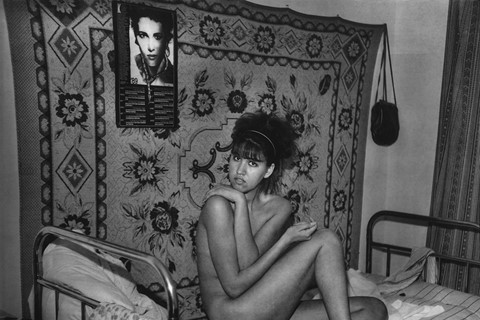

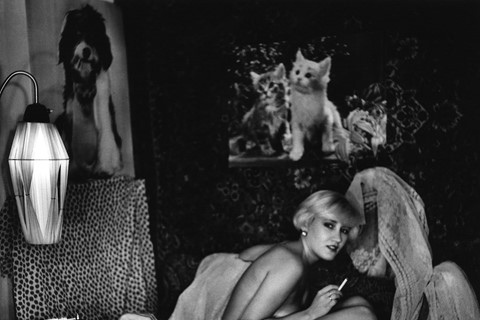

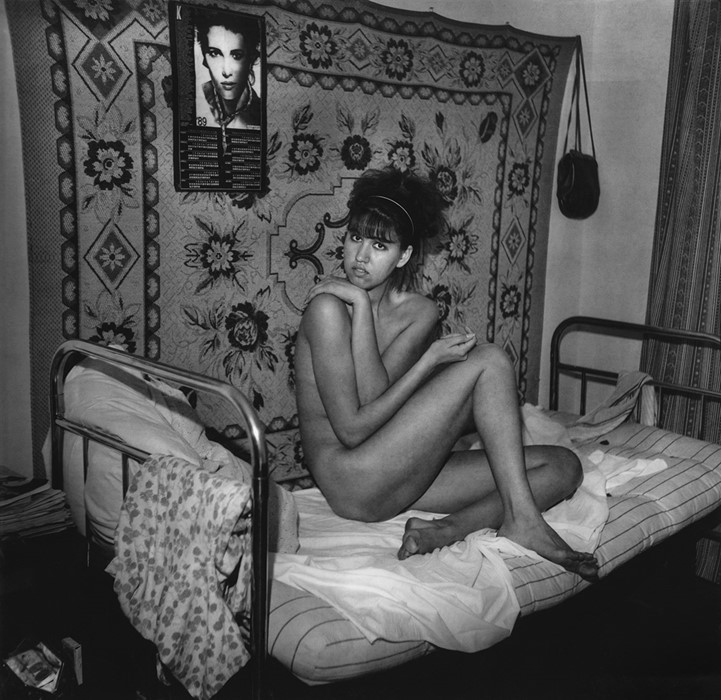

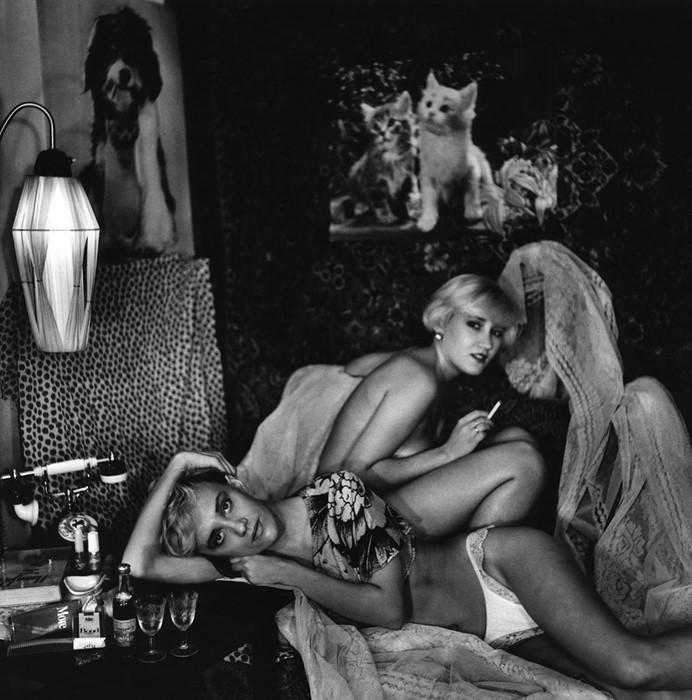

It is difficult to tear your eyes away from the people in Nikolay Bakharev’s newly published monograph, Novokuznetsk, so intense are their expressions. Consistently fixing their gazes to camera, his subjects bear all, both literally, in many cases posing nude or semi-nude, and emotionally. Paradoxically, these apparent exhibitionists who flirt with the camera seem strangely vulnerable, and behind the mask of performance it’s possible to detect flickers of insecurity – a cry for help or reassurance. But the camera’s cold, unflinching lens offers no comfort, serving only to objectify more acutely what is in front of it.

Bakharev, a mechanic-turned-photographer, took the images mostly between 1986 and 1993 while working as a Communal Services Factory photographer in the remote city of Novokuznetsk in south-west Siberia. As a sideline he photographed local inhabitants in all manner of places from schools to swimming pools, parks, nurseries, and at weddings – wherever his services as a portrait photographer were required. He also solicited work as a black market portrait photographer on the public beaches of eastern Russia, inviting clients to be photographed in their homes after the shoot had finished.

More often than not the photographs would take a turn for the erotic with the men and women stripping for Bakharev and posing provocatively for the camera. What he was doing was highly risky since it was illegal to make or distribute images containing nudity during Soviet times. So Bakharev and his subjects worked in secret.

“For the most part, he's seeking a psychological truth,” says Vladimir Dudchenko, director of Grinberg Gallery in Moscow, which represents Bakharev’s work. “For him, his subjects are the world that has to reveal itself. Generally he offered to make beautiful photos [of] people he met on the beach or elsewhere. In the process he would produce something for them and would keep something for himself. Everybody wins!”

Critics of Bakharev, who came to prominence in the late 1980s, claim the photographs verge on the pornographic, but as Aaron Schuman suggests in his accompanying essay in the book, there is more going on than may be apparent at first. “It would be easy to misinterpret these images as simply the pornographic imaginings of a manipulative and dirty old man, yet there is something else within them – in the subjects’ eyes, in their frankness, in their curiosity and collusion, as well as in their surroundings.”

What that “something” is the book or Bakharev doesn’t make explicit. Indeed, we know nothing about the sitters – the book does not reveal their identities or offer any information about their backgrounds. That’s not to say the images don’t invite inquiry, and the more you look, the more you notice – photographs on the wall, posters of pop-stars, artworks that seem to echo the people in the frame. As multi-layered as the images are, they pose more questions than they answer.

“Nikolay has a way of photographing people that it is really unlike anyone else,” says Gregory Barker of Stanley/Barker, who published the book with the support of Grinberg Gallery and Julie Saul Gallery in New York. “His work has a strange tenderness that is wonderful.”

A huge part of what gives the images their power and intensity is the undeniable trust Bakharev’s subjects give to him and how they open themselves up before his and his camera's gaze. “[During a shoot] Bakharev… talks and talks and explains and explains,” says Dudchenko. “His models start to lose [their] defenses, and are lured into his world. At some point they start to just trust, to reveal themselves, and that is when some inner truth starts to shine through.”

Novokuznetsk is available now, published by Stanley/Barker.