As several of the German photographer’s influential works go on display, we reveal the story behind her seminal Self-Portrait with Leica, and its relevance as an icon of modernist photography

While photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Man Ray and Brassaï are widely credited with establishing Paris as the centre of modern photography in the 1930s, the similarly innovative and influential German photographer Ilse Bing, who also resided in the city at that time, is more frequently overlooked. Bing was one of the first image-makers to master and shoot exclusively on the hand-held, small-format Leica camera, which would soon thereafter revolutionise the medium. She was nicknamed the “Queen of the Leica” by fellow photographer and critic Emmanuel Sougez, who praised her ability to capture the “enchantment with which reality is enveloped”.

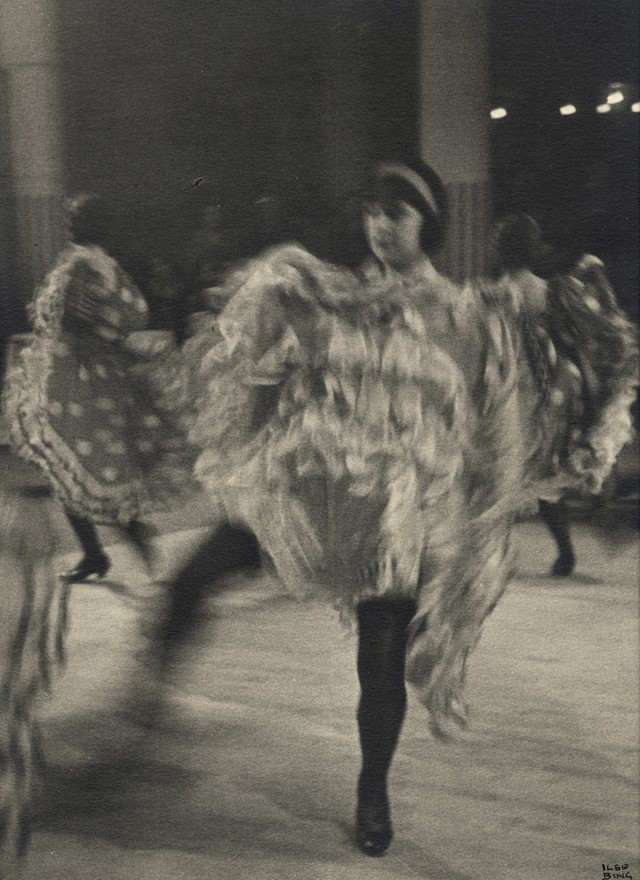

The self-taught Bing was a creative sponge, admiring and borrowing from a variety of contemporary movements – from modernist 'New Photography' to German 'New Objectivity'; from the work of Alfred Stieglitz and American social realism to Surrealism and the Bauhaus – yet throughout her career, she maintained a unique and distinctive style. Her work boasts a distinct dynamism thanks to her frequent employment of unusual angles, cropped compositions and aerial views (she is said to have turned her photographs upside-down and sideways, agonising over their compositional relationships).

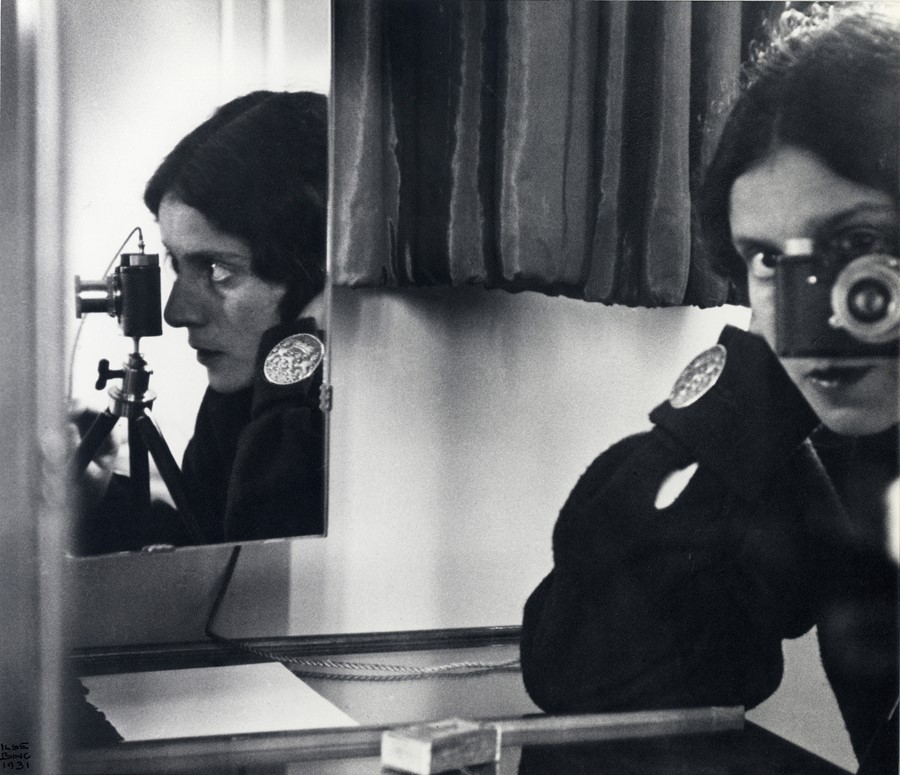

The above self-portrait of the photographer and her camera – taken in 1931 and currently on display as part of the Barnes Foundation’s exhibition of French photography from 1890 to 1950, titled Live and Life Will Give You Pictures – is one of Bing’s most famous works, and a key icon of modernist photography. It is a compositionally complex image that shows Bing capturing herself in a mirror with another mirror (possibly the opposite side arm) angled so as to reflect her and her beloved Leica in profile. It demonstrates a broad range of tactile tones and textures, from the deep-black, slightly bobbled fabric of Bing’s jacket, to the oversized, rippling silver button on its sleeve, to the sheeny curtain, with its deep folds, glistening behind her. The objects on the desk in front of her – a sheet of paper, an electric cord and what looks like a box of matches – interrupt the formality of the set-up and point to the image-maker’s interest in the banal details of urban living.

The double presence of the artist at work, and the intentness of her gaze, serves to highlight the newfound independence that women were enjoying at the time, while the prominent inclusion of the camera symbolises the burgeoning technical revolution of the period and the fresh opportunity for creative expression it enabled. This portrait was taken just a few months into Bing’s ten-year sojourn in Paris, as her adventures in photography were just beginning – she would go on to enjoy great success as a press, fashion, portrait and documentary photographer in the city before the Second World War forced her to flee to New York on the grounds of her Jewish heritage. The interest in merging intuition and poetry with scrupulous composition and shrewd technical skills that would come to define her work is already apparent here, as is her devotion to her medium. “I didn’t choose photography; it chose me,” she reflected in later life. “I didn’t know it at the time. An artist doesn’t think first and then do it, he [sic] is driven. Now over 50 years later, I can look back and explain it. In a way, it was the trend of the time; it was the time when you started to see differently… And the camera, that was, in a way, the beginning of the mechanical device penetrating into the field of art.”

Live and Life Will Give You Pictures is at the Barnes Foundation until January 9, 2017.