We sit down with Youssef Nabil to discuss 20th-century film, saving Salma Hayek, and his dreamlike images of Oriental nostalgia

Youssef Nabil is an Egyptian artist and photographer whose instantly recognisable images capturing a golden age of Arabian cinema have been exhibited everywhere from London's Victoria and Albert Museum to Art Basel. Born in Cairo in 1972, Nabil’s career famously took off when revered fine art photographer David LaChapelle spotted him shooting outside a hotel he was staying in Cairo in 1992; they were introduced on the spot, Nabil quickly offering to assist LaChapelle for free, and before he knew it he was on a plane New York to be LaChapelle's assistant. It was the beginning of a long journey for Nabil – just a few years later he moved to Paris to work with with Mario Testino, before breaking away in the late 1990s to launch his solo career.

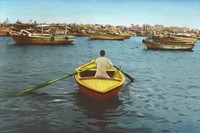

In spite of his all-star resumé, Nabil's introduction to his medium was decidedly lo-fi. As a young and hopeful student he was rejected from every art school and film school in Egypt, and so spent years learning the traditional techniques required to hand-paint monochrome photographic stills for film studios, taking his education from the masters of the craft – Armenian photo-retouchers working in downtown Cairo. Many of these craftsmen found themselves out of work after the introduction of colour film, so Nabil would pay them for lessons, spending hours painstakingly tinting black and white photographs.

This slow process appealed to his cinematic sensibility. "I think I always had a very visual memory – images speak so much to me," Nabil tells AnOther. "I knew from a very young age I wanted to work with images, especially growing up in Egypt and watching a lot of Egyptian movies. We love cinema in Egypt, and have a huge movie industry. I was introduced to so many ideas through cinema – that was my education."

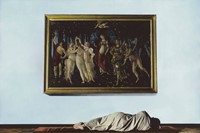

As well as an aesthetic apprenticeship, Nabil's fascination with cinema taught him about beauty and mortality. "Through film, I became very concerned with death as a child – I would ask my mother where the actors and actresses were now, and she would tell me they were dead," he says. "This affected me, subconsciously, as I realised I was in love with these beautiful dead people. I understood from that point that we’re all here to die, but the camera is the tool to preserve who I love after they, and I, die."

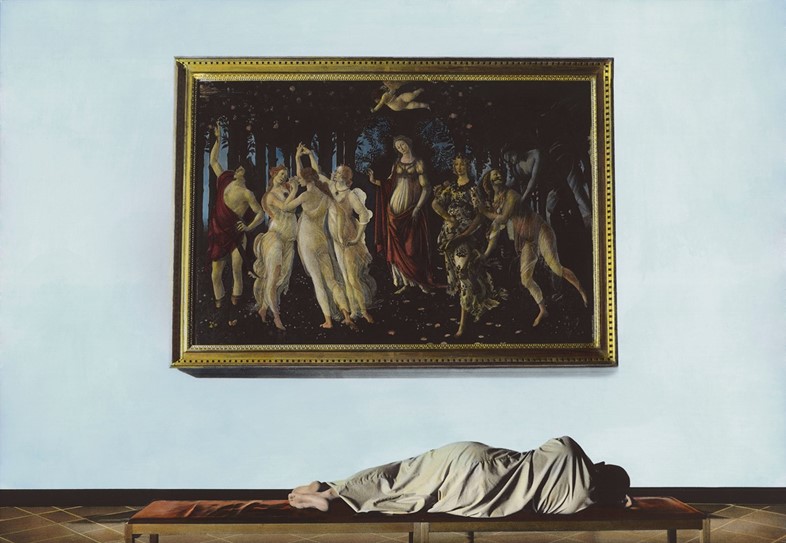

This notion of the photograph as a tool for preservation seems to sit well with Nabil's practice; his works are often filled with alluring colours, emitting a hazy, almost funereal glow over their subjects. The photographer tends to abandon depth and reality in favour of this vibrancy, but the narrative at work in his scenes remains unfettered. His compositions recreate scenes of bygone Arabian Hollywood glamour – belly-dancing girls seduce fez-wearing gentlemen in highly provocative and sensual scenes, tinted with the old colouring techniques of his apprenticeship with the Armenian masters. They often look like they might have been cut straight from a 1950s film spool, found in the depths of a dusty archive.

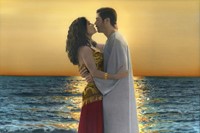

Alongside his more conceptual work, Nabil has also shot celebrity portraits for the likes of Charlotte Rampling and David Lynch, frequently turning his sitters into fictionalised movie stars from his own imagined world. In 2015 he made a video artwork starring Salma Hayek and Tahar Rahim entitled I Saved My Belly Dancer, accompanied by a series of photographs dealing with themes of love, gender and relationships in an Arabic society.

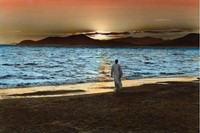

Loss plays an important role in these stories, Nabil explains: "Leaving is always part of the subject of my work. There is no such thing as a perfect situation or place, but when you grow up often you have to leave. My first video was entitled You Never Left and it deals with the relationship between leaving, and dying. I often use the imagery of a sunset – it’s the end of a period, the death of a day."

The West’s historical fascination with Orientalism meant it was regarded as a heady, exotic and mystical land of beauty, until that idea fell apart with the rise of mass media, and easy travel and cheap tourism. As a native Egyptian, Nabil often says this theme isn’t in his mind when working, yet his images resonate with these ideas to a Western audience, adding to his appeal. "I’ve always admired belly dancers because they’re such powerful women, they’re practically naked, dancing, handling their sexuality, dealing with traditional rules, and they’re still are out there doing it for a living," he explains. "To me Salma Hayek could play one of those women – in my mind she has always been an Arab woman, not just Mexican. Sexuality is there in Egypt, and it’s there in a very Oriental way. I’m not seeking to shock in how I present sexuality."

And what does Nabil have planned next? "My next project is a 28-minute video called Arabian Happy Ending, and it’s about sex in the history of cinema," the artist says. "It's something I saw all the time on television, but we are still not allowed to talk about in real life. It’s full of this nostalgia I always feel. The film is cut with all the scenes of people kissing, people in bed, even scenes of men or women together. In Egypt you can watch these things on television, but if you kiss a girl in the street you go to jail. If you kiss a man or a girl kisses a girl, that’s even worse. It’s all about taboos, and hoping for a happy ending in love for everyone. That’s why I wanted to do this."

Youssef Nabil's work is on display as part of Portrait de L’artiste en Alter at Frac Normandie, Sotteville-lès-Rouen, France, until September 4, 2016.