“My subjects are aware of their bodies, they’re not objects of desire.” The celebrated photographer discusses subverting the status quo for her new Berlin-based exhibition

Look at French-born photographer Camille Vivier’s work and you’ll find that the women depicted are often nude – and much of the time, they’re looking right back at you. Existing in a world that’s been thrown off-kilter and re-shaped by her gaze into something altogether more surreal, Vivier explores “the strangeness in ordinary things”; a reimagining of reality rather than a documentation of it. It’s this particular uncanny charm that has seen the photographer (who won the inaugural photography prize at the Hyères Festival in 1998, just a year after graduating from Central Saint Martins) become a favourite in fashion – whether capturing softly-illuminated still lifes for Dazed and Confused or editorials for AnOther.

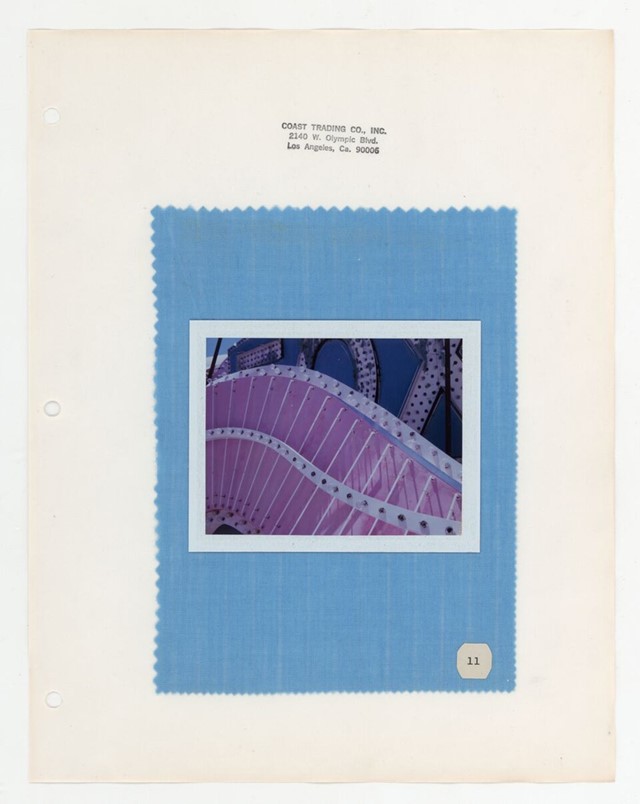

Her latest exhibition, Simili, held at Berlin’s Galerie für Moderne Fotografie, sees a meeting of worlds: the municipal yet strangely avant-garde sculptures that lie forgotten in the suburbs of Paris are contrasted with a collection of polaroid portraits of her female subjects. “Photographing the statues is about questioning the boundaries of beauty and ugliness,” asserts Vivier. “They are latent signs of the city’s ruin, as well as echoing these 17th-18th-century parks that we call Folies, like Bomarzo. They often have an anthropomorphic shape, which refers to the nudes – their brutalist aspect and roughness have an odd sensuality and decadence.”

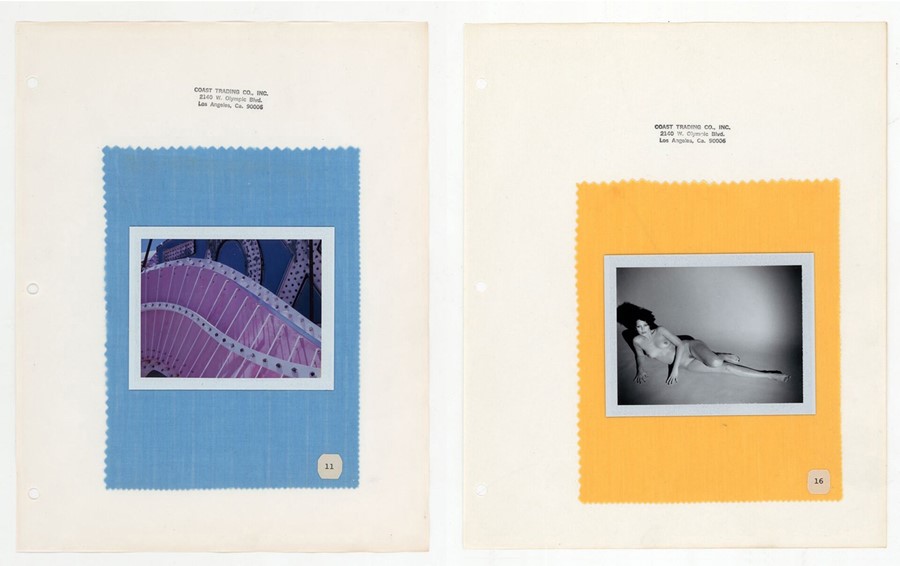

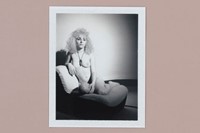

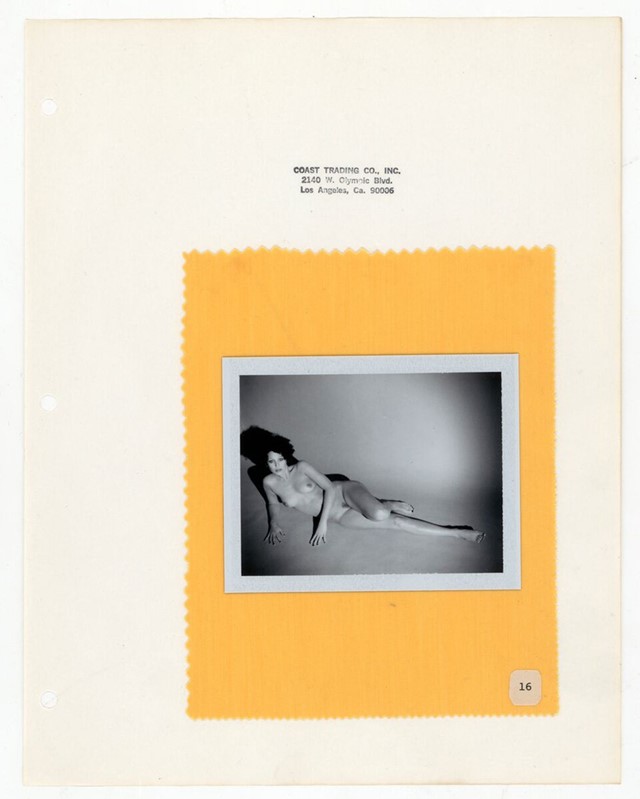

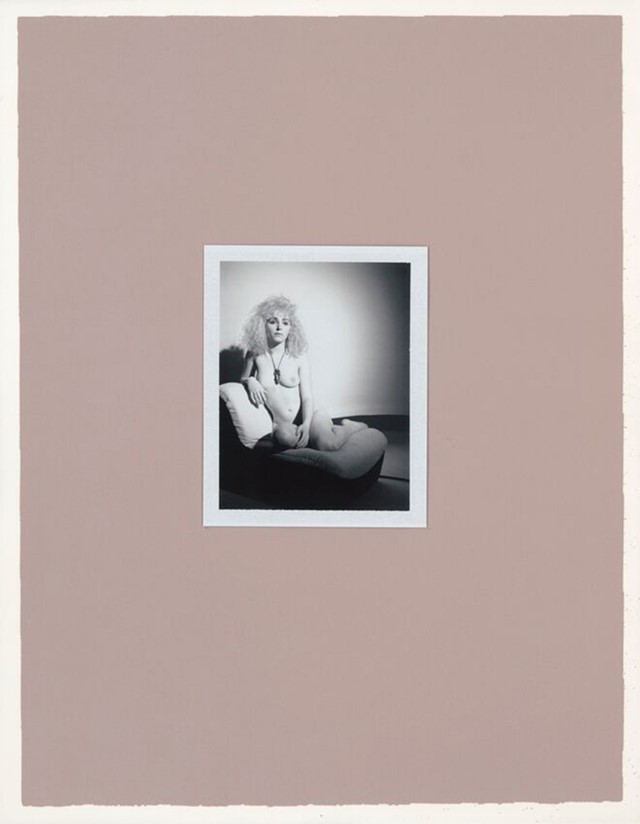

Some images from her new series Olympic, are displayed on pages of a 1970s fabric catalogue, found by Vivier amongst her possessions. “By associating them, I had this will to create an object, to consider the photograph as an element that would be recontextualised. It questions what inhabits and what’s inhabited, playing literally on different layers. Here naked girls strike poses on bare surroundings, while high rise buildings seem to collapse.” Another series, Sample, sees polaroids – including images of constructivist marionettes by Italian artist Luigi di Veronesi – pasted on painted cardboard, giving the illusion of something almost like a children’s book.

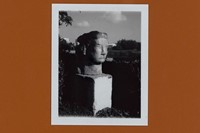

Vivier isn’t frustrated by being termed a “female” photographer – if anything, she believes her womanhood provides her with a privileged viewpoint, giving her work, and especially her nudes, a kind of honesty uncoloured by desire. As she puts it, what began as an aesthetic statement became a social and political one. “Women (creating) nudes of other women is not such a common thing,” she ponders. “I think about Sylvia Sleigh, a great painter, or Friedl Kubelka, an Austrian photographer, among others. The female body seems to have been the subject of men for ages… As a woman, my vision is very different, more gentle, and less aggressive. My way of photographing nudes is quite neutral; it talks about femininity but in a more abstract way. The women I photograph are smart and aware of their bodies and power, they’re not shown as objects of desire, and I photograph all kind of bodies, far from beauty diktats.”

“Men act and women appear,” John Berger famously wrote, back in 1972. “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” Not so in Vivier’s world; here women are instrumental in their own representation, and it's just this subversion of the patriarchal structures underpinning her form that sets Vivier apart.

Camille Vivier: Simili runs until April 22 at Galerie für Moderne Fotografie, Berlin.