Erotica and botany collide in the iconic artist's photographs of flora, as a new LACMA retrospective demonstrates

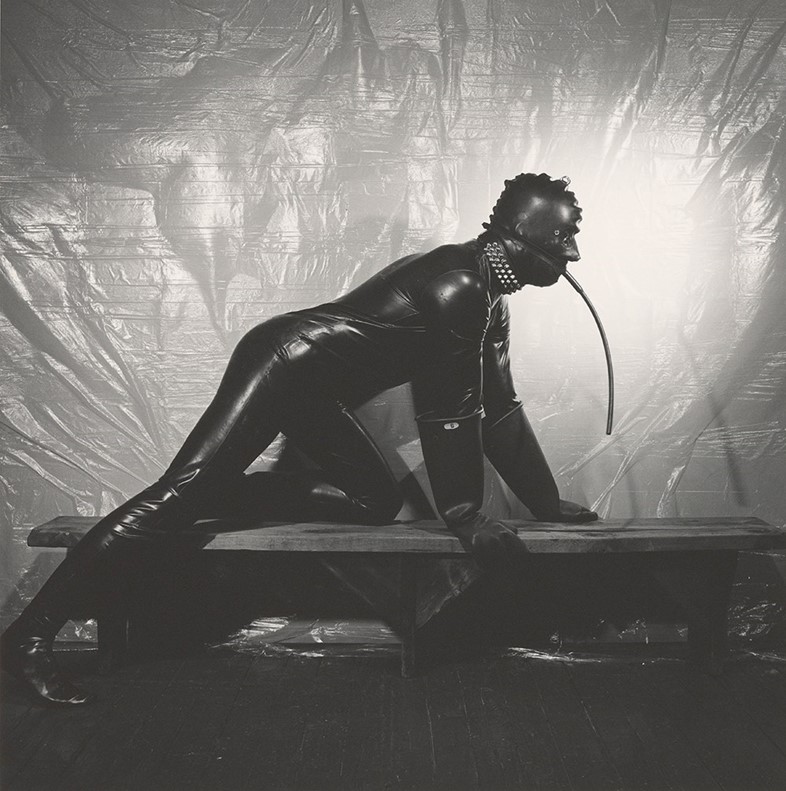

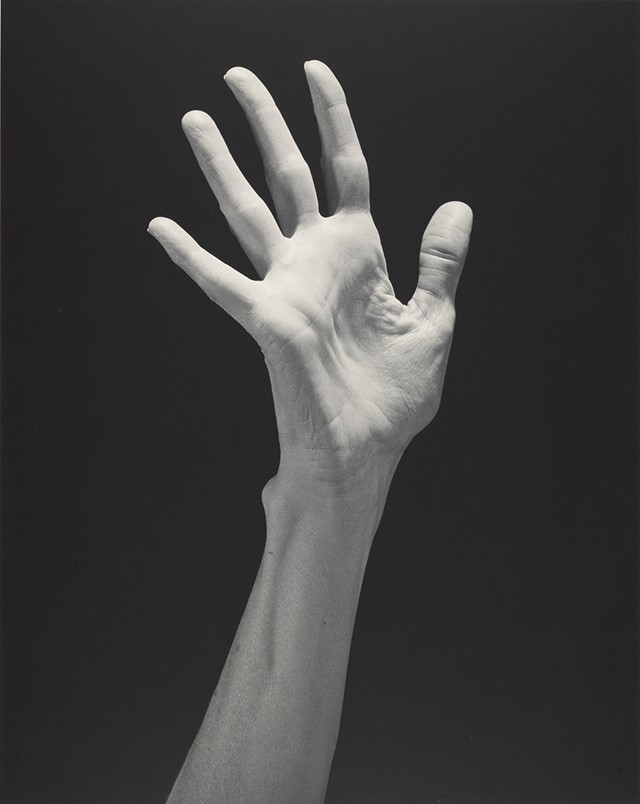

As both the unlikely darling of New York’s avant-garde art galleries and a pivotal figure in the city’s burgeoning gay scene, artist and photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s career was nothing if not duplicitous. On the one hand, he was heavily preoccupied with classicism: his rippling, muscular, anatomical nude studies recall Michelangelo’s David, while his sculptural images of hands have often been juxtaposed with casts made by French sculptor Rodin no less than a century earlier. On the other, he spent seven years photographing highly stylised and explicit S&M scenarios with friends and acquaintances from the gritty underground, compressing gay culture into photographs which, while they were condemned by his contemporaries as controversial, are now considered some of the most iconic works of his era. He dined with the elite of Manhattan’s art world by day, and slept with creatures of the city’s night when the sun went down. His life and career were characterised by inherent dualities.

Mapplethorpe’s floral still lifes, a series of up-close photographs of the beautiful, hairy blooms in all of their fragility and vivid power, are perhaps the most intense distillation of the artist’s doubleness. The photographs draw on a rich and storied history of artists depicting flora – from the Dutch masters, whose gloomy reimaginings placed wilting blooms next to preying insects and glazed shells, to the black and white studies Helmut Newton made in the late 1960s. And yet, they’re also in possession of an unignorable and intense sensuality, all billowing texture and glistening, human-like hairs. The magnetism is undeniable.

There’s an inherently sensual undertone to Mapplethorpe’s studies, too. First and foremost, on a scientific basis: flowers formulate for the purpose of attracting bees, to encourage pollination – they are to the plant world what lace negligées and metal dog collars are to the human. Like the latex-clad figures peacocking in his more explicit works, their vivid colour draws the viewer inwards: the sexual organs are largely external, leaning provocatively out of their enveloping petals to create a yonic emblem of reproduction. In Mapplethorpe’s case, the proximity with which they are captured adds an irresistible and decadent draw. Petals ripple provocatively, suggesting labia or tumbling silk, while the tiny prickling hair of a stem comes under close examination through his determinedly all-seeing lens.

“Whether it’s a cock or a flower, I’m looking at it in the same way… in my own way, with my own eyes” – Robert Mapplethorpe

The sensuality of these works might have been caused, on a subconscious level, by the close cerebral quarters they shared with his more explicit pieces. “I like to look at pictures, all kinds, and all those things you absorb come out subconsciously one way or another,” Mapplethorpe once reflected. “You’ll be taking photographs and suddenly know that you have resources from having looked at a lot of them before. There is no way you can avoid this. But this kind of subconscious influence is good, and it certainly can work for one. In fact, the more pictures you see, the better you are as a photographer.” What’s more, Mapplethorpe categorically stated that he treated all of his myriad subjects equally. “My whole point is to transcend the subject… Go beyond the subject somehow, so that the composition, the lighting, all around, reaches a certain point of perfection. That’s what I’m doing. Whether it’s a cock or a flower, I’m looking at it in the same way… in my own way, with my own eyes.”

For his part, Mapplethorpe was under no disillusion as to the selling power of such works – which lent the owner an air of controversy even as they fit into a perfectly acceptable and aesthetically pleasing norm. “Sell the public flowers…” he once proclaimed, defining precisely this sentiment. “Things that they can hang on their walls without being uptight.”

It’s this manifold and complex duplicity which forms the foundation for a new retrospective of Mapplethorpe’s extensive career at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, entitled Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium. The exhibition, which has been no fewer than six years in the making, explores Mapplethorpe’s oeuvre through a collection which comprises drawings, collages, sculptures, Polaroids, photographic works and two rarely seen moving image works. “He [Mapplethorpe] seemed to enjoy playing with those contrasts between his downtown reputation as a rebel and a provocateur, and his uptown reputation as a maker of beautiful society portraits, beautiful floral still lives, etc,” LACMA curator Britt Salvesen explains. “So we took that as a point of departure.” It’s also no coincidence that the exhibition that LACMA is showing concurrently, entitled Physical: Sex and the Body in the 1980s, is similarly concerned with the bodily; the pairing is intended to place Mapplethorpe within a context of artists working in and around sexuality in the 1980s. Meanwhile, at the neighbouring institution the J Paul Getty Museum, a companion show will look more closely at Mapplethorpe’s fascination with classical form.

The intense theoretical conversation surrounding Mapplethorpe’s work continues now much as it did at the time of the flower photographs’ conception; art historians consider the age-old tradition of the still life that he worked in even as they juxtapose the sensual photographs with similarly erotic images made concurrently. One thing is for certain, however – the artist’s pursuit of perfection informed everything he created, from S&M studies and extraordinarily intimate anatomical works, to still life works about nature. “I am obsessed with beauty,” he once confessed. “I want everything to be perfect, and of course it isn’t. And that’s a tough place to be because you’re never satisfied.”

Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium runs until July 31, 2016, at LACMA and the J. Paul Getty Museum.

![Lead]](https://images-prod.anothermag.com/900/azure/another-prod/350/3/353692.jpg)