The trailblazing feminist artist talks disillusioning young creatives, starring in soft porn for money, and her unexpected affinity for cats

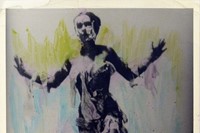

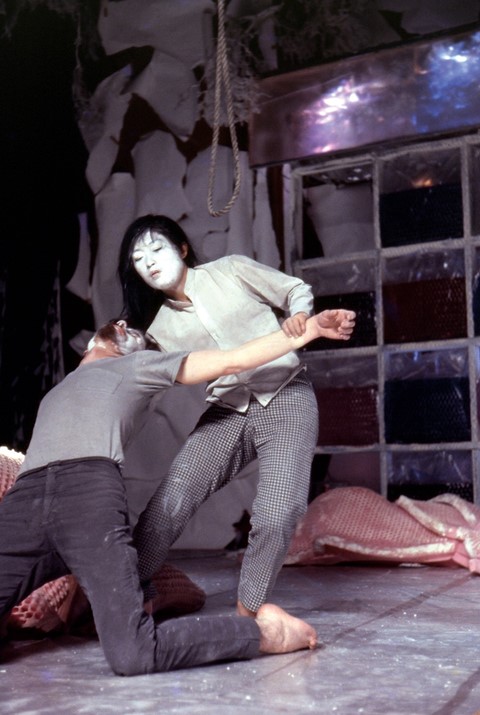

Raw meat, smeared paint, writhing naked bodies, a paper scroll unfurling from a vagina: these are the images inevitably conjured when mentioning American artist Carolee Schneemann. However, Schneemann’s five-decade-long practice extends across mediums and modes: from the erotic, tactile, aesthetic, and ecstatic, to the furious and the political. Her work – from painting, video, performance, dance, film, installation, and writing – stands as an exceptional record of radical experimentation.

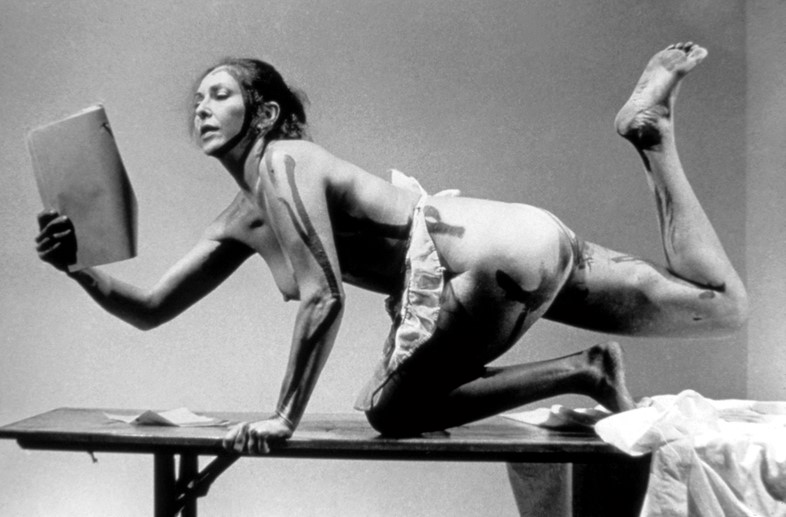

Schneemann is best known as a trailblazer. Working at the much-maligned vanguard of performance art and feminist art, works such as Meat Joy (1964), Fuses (1964-66), and Interior Scroll (1975) are now canonical, belying their former notoriety. Fuses, a gloriously intimate film of the artist and her then-partner making love, was created at a time when American movies were barred from using the word ‘vagina’, or even showing pubic hair. Schneemann was criticised by an overwhelmingly male art world for self-indulgence and narcissism; they failed to grasp that nudity could be used to reject objectification, through self-ownership and self-definition. Her gleefully corporeal practice has acted as a gateway drug for generations of artists, empowered to make unapologetically personal and political work with their bodies, or without.

Now in her seventies, Schneemann is a force to be reckoned with. From her beginnings as a painter in the late 1950s, she asserts her identity as a painter above all, yet continues to create work across disciplines. Recent work includes Terminal Velocity (2001), a photographic homage to the lives lost falling from the World Trade Centre, or Devour (2007), a film study of American life in an age of dramatic inequality. Her challenge now is to escape the legacy of the 60s and 70s; to be seen afresh, and not only for groundbreaking performances half a century ago.

On reclaiming the female nude…

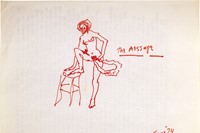

“When I made Eye Body (36 Transformative Actions For The Camera) (1963), I was working against the inheritance of passive nudes, and the hard, mechanised body of pop art. Resistance to my work from feminist theoreticians really hurt: they ignored the structure, concept, and formulation of the work by objecting to its sensuousness, and said I was playing into patriarchal visions of womanhood. There’s tremendous stress around the female body. Is it erotic, aesthetic, or political? Using the naked body can be very deep and have consequences, or it can be vacuous, silly, and banal. Time often reveals which.”

On her advice for aspiring artists…

“Interrogate your motive for being an artist. Might we possibly have enough artists? Do you want be an artist because your options are so bleak? Some students say they have to be artists because everything else is so boring, commercial, and predictable. There’s a fantasy that if you have a name in our culture, you’ll have an income – that hasn’t happened for me yet. I feel I have to disillusion young artists: to let them know I had to be a dog-drier in a pet shop, I stood around in soft porn films, I sold cheese on the highway. Economics and real estate are also key problems in finding spaces where artists can put their energies as a group. Artists are increasingly going online, but with virtuality there’s the loss of materiality, of feeling in your flesh. I would recommend activism instead. We’re on the edge of blowing up everything that makes our history go forward. It’s time for resistance.”

On the intimate relationship between humans and cats…

“Cats teach us attention, patience, how to look hard and slow at things. Their physicality influenced my early performative principles, thanks to their sense of bodily certitude and the way they measure their strength and energy. As Kitch’s Last Meal (1973-76) and Infinity Kisses (1981-88) illustrate, there’s an intense closeness, love, and communication between humans and cats.”

"There’s a pattern whereby female artists get more attention once they’re no longer deemed sexually attractive – the sexual instincts of critics stop diverting their palettes." – Carolee Schneemann

On five decades in the art world, ageism, and making art in your seventies and beyond…

“People need to know that you don’t just shrivel up and dry out. On the other hand, the body becomes more susceptible to problems. You have to get used to losing people. Dying is infuriating and boring and I detest it; it’s so wasteful. You work, you begin to achieve something, and then you die. When I was younger I suffered from reverse-ageism – people wanted to fuck me, which distracted from the work. There’s a pattern whereby female artists get more attention once they’re no longer deemed sexually attractive – the sexual instincts of critics stop diverting their palettes. Now they don’t want me sexually, people focus on the work more. I feel about 36, so that’s an interesting dilemma!”

On stubbornness, courage, and success…

“I was told my work was crap for 20 years. Succeeding doesn’t require courage so much as being stubborn. When I started making kinetic theatre works, I didn’t even have the courage to stand upright! I used to direct actions while crawling around; thankfully the pleasures of Meat Joy changed that. Shut yourself in a room where no-one can bother you. You don’t have to be good – just see what happens, and keep going.”

Carolee Schneemann: Unforgivable runs until March 11, 2016 at WORK Gallery, London.