Artist first and nun second, her unbridled creativity bore years of provocative printmaking

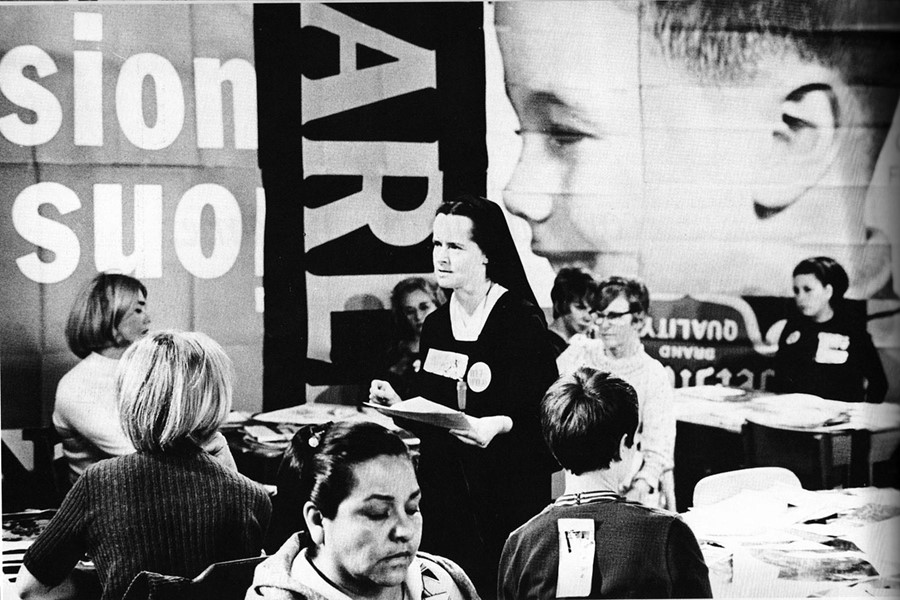

Who? The habited yet unabashed, avant-garde American graphic artist Sister Mary Corita Kent, rose to international renown throughout the 1960s on account of her radical visual amalgams and pop-culture iconography, with Catholic instruction. An Iowan by birth [Fort Dodge, 1918] Frances Elizabeth Kent was raised nevertheless by the City Of Angels, Los Angeles. After entering the Roman Catholic order the Sisters Of The Immaculate Heart Of Mary in 1936, Kent attended assorted classes at the city’s Otis College Of Art & Design, Chouinard Art Institute, and the University Of Southern California, before obtaining a Master of Arts in 1951; the same year in which she exhibited her inaugural silkscreen print.

Kent inhabited Immaculate Heart Order from 1938 onwards, where she also chaired the college’s Art Department, educating and collaborating with innumerable luminaries in the process; Saul Bass, John Cage, Charles and Ray Eames, Buckminster Fuller, and Alfred Hitchcock amidst such. Kent departed the Order in 1968 for Boston’s Back Bay, wholly devoting herself now to practising graphic art, and acquired eminent commissions while actively endorsing innumerable causes.

She was introduced to printmaking whilst attending Master’s classes at the University of Southern California, and by the early '50s Kent had begun authoring highly experimental juxtapositions of scripture, everyday packaging, products and trademarks, commercial phrases and recognisable identities, all executed through pop art’s kaleidoscopic lexicon. Lichtenstein, Ruscha and Warhol’s contemporary, Kent’s oeuvre endures, by contrast, theologically contemplative; unexpectedly spiritual and wholly devout, despite her joyous consumer’s hues. She passed away at last in 1986, after an ongoing battle with cancer.

What? Immaculate Heart College Art Department’s Ten Rules, authored by Kent, contains the sage proclamation of aural theorist and experimental composer John Cage, for Rule Ten; “We’re breaking all of the rules. Even our own rules. And how do we do that? By leaving plenty of room for X quantities.” Amply encompassing X quantities through her provocative synthesis of pop culture with scripture, consumption imperative with celestial reflection, Kent allowed audiences to excavate unchartered terrains of epistemological and theological inquiry.

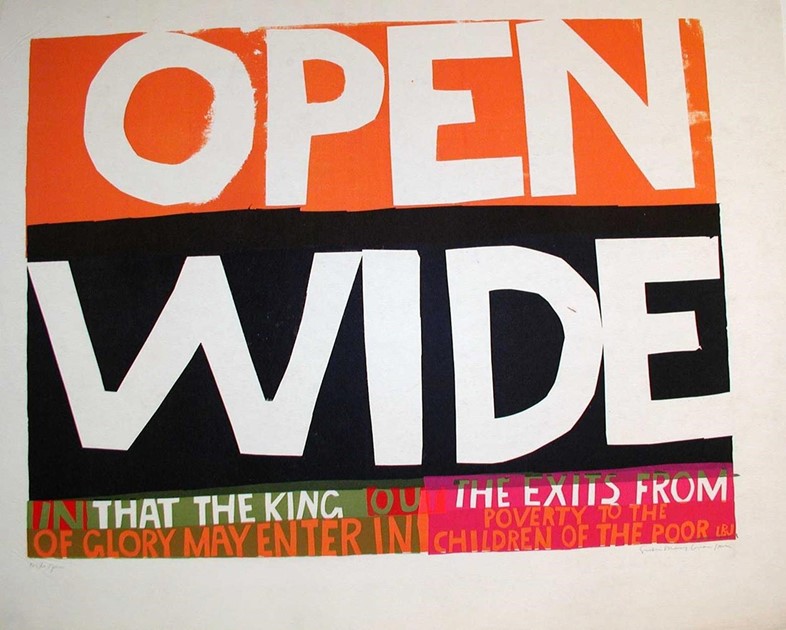

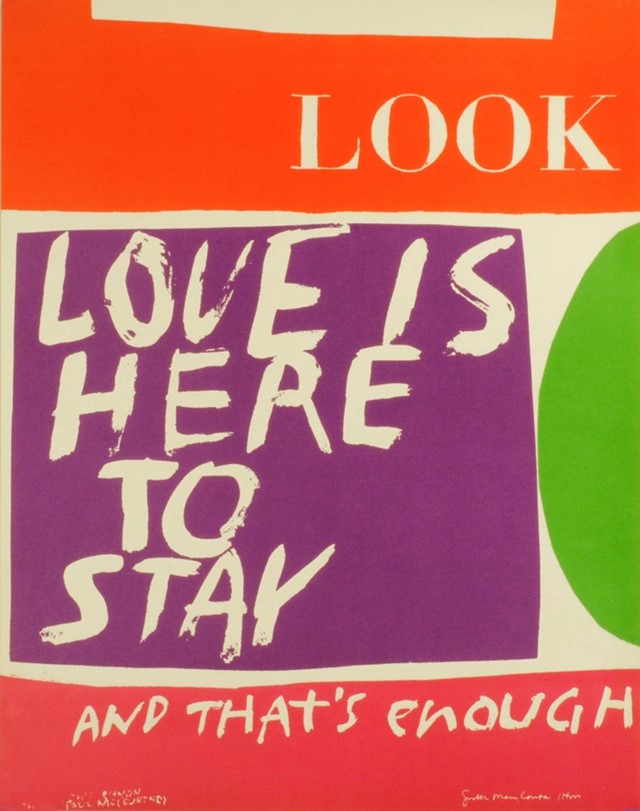

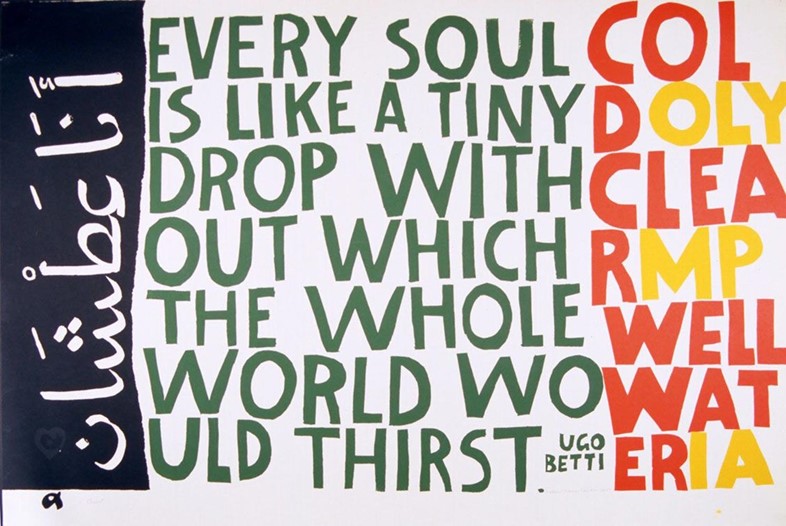

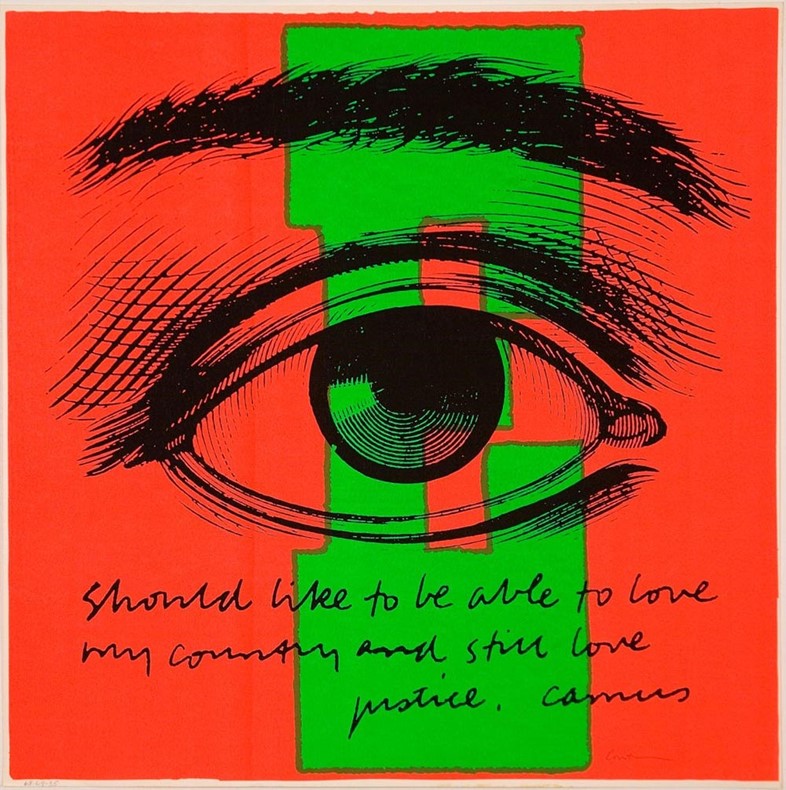

She drew omnivorously from newspapers, trademarks, literary texts, storefront signage, popular song lyrics, reportage and celebrity phrase, her vibrant serigraphs entwining traditional printmaking, illustration and photography, and offered dissentious commentary upon the immense civil agitations then characterising much of the '60s and '70s. Deepest swathes of coloured Matisse-torn paper buttress Warhol-influenced advertising reproductions, with longing sentences drawn from Camus, Nin, Stein and Whitman, all garlanded by the enticing palettes of Esso, General Mills, Sunkist and enriched Wonderbread.

This typifies Kent’s entire oeuvre. “Makes Meatballs Sing,” declares her 1964 work, Song About the Greatness. An appropriation of Del Monte tomato sauce’s rather ambitious mantra, within the colossal word ‘Sing’, one finds an excerpt from Psalm 97; “Let the ocean thunder with all its waves the world and all who dwell there the rivers clap their hands the mountains shout together with joy before the lord for he comes’. Another archetypal composition from 1964, Enriched Bread, variously combines Wonderbread’s primary-coloured Calder-reminiscent hues and assertion, “helps build strong bodies 12 ways STANDARD LARGE LOAF”, with a handwritten extract from Camus’ meditative 1954 essay, Create Dangerously; an apt characterisation perhaps of Kent’s enduring raison d'être.

Why? Integrating a celestial dimension within pop art’s often scathing mimicry of commodity exchange and consumerism behaviour, Kent’s work offers divine contemplation through the unexpected realm of advertising. She appropriates that richest visual lexicon wholly designed to entice and persuade by assimilating trademarked identity, alluring colour palettes and hyperbolic consumer imperative or promise, with unequivocal observation, her deceptively buoyant screenprints disarm even now. Possessing inherent condemnations of then-pressing civil actions and unimaginable disparities across belief, gender, income and race, both within America and abroad, Kent’s enlightened deployment of faith and iconography throughout her compositions reinforced her campaigning in truly unimaginable fashions. She transformed often inaccessible scripture into lay messaging that held contemporary applicability, irrespective of belief, with mass appeal, and all within her alluring aesthetic.

Visionary Kent and her progressive order went ostracised nevertheless by then-Archbishop of Los Angeles Cardinal James McIntyre as an iconoclast. Another 1964 work, The juiciest tomato of all, intimated Mother Mary was, in fact, such largely accounted for his ire. Throughout the following years she and hundreds of other Immaculate Heart Of Mary sisters encountered escalating demands from McIntyre to return to archetypically more conservative elements of Catholicism. Obstinately refusing, Kent departed her beloved order at last in 1968. Pursuing serigraphy wholly in Back Bay now, receiving several large-scale commissions such as that of the U.S. Postal Service in 1985 to create her emblematic LOVE stamp, which sold more than 700 million editions, Kent’s sacred offering to pop art assures her indelible legacy, a rightful standing alongside the genre's more acknowledged arbiters.

Some of Sister Corita Kent's work is on display as part of Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia, which runs until February 28, 2016 at Walker Art Center.